Philip Ball investigates how cells use condensed ‘blobs’ to collect the molecules involved in regulating genes

It’s not what you’ve got, it’s how you use it. That seems to apply as much to cells as to people. As we grow from an embryo, lineages of replicating cells start from a versatile stem-cell state and end up self-assembling into tissues with specialised functions. This specialisation depends not on which genes the cells have, but on activating and deactivating the right genes at the right time. How does the machinery that turns genes into proteins know which part of the genome to read in any given cell type? ‘To me that is one of the most fundamental questions in biology,’ says biochemist Robert Tjian of the University of California at Berkeley in the US: ‘How does a cell know what it is supposed to be?’

Two decades on from the completion of the Human Genome Project, it’s clear that we won’t understand complex organisms like us – and reap the medical benefits – from a list of the genes and other components that guide cell behaviour. ‘We now have a fairly complete catalogue of the cell’s genes and molecular components,’ says Clifford Brangwynne, a biophysicist at Princeton University in New Jersey, US. ‘And yet we seem to be still far from understanding the principles that underlie their collective organisation.’

The switching on and off of genes, called gene regulation, is one of the most important aspects of that organisation. Like everything in biology, it’s complicated. But over the past decade or two it’s become clear that this process challenges the way we have thought about the logic of life ever since DNA was revealed as a molecular information bank almost 70 years ago.

For gene regulation isn’t a matter of straightforward, digital transmission of information that relies on chains of lock-and-key recognition and binding of programmed biomolecules. Instead, it seems to involve something much more collective and dynamic at the molecular scale. Regulation is achieved not through selective molecular handshakes but from brief snatches of conversation within a bustling throng of diverse molecules, gathered into a loose cluster amidst the genes themselves.

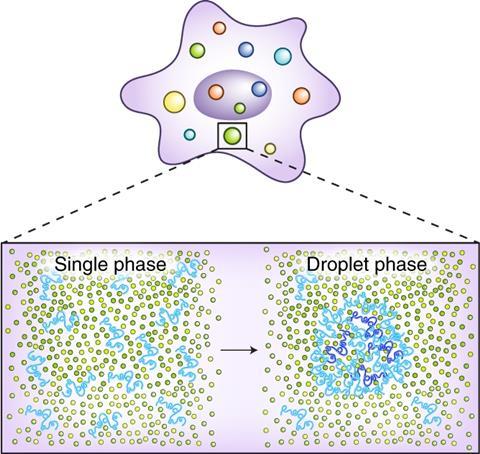

How that happens is still being debated. One view is that the molecular crowd is convened by the collective physics of phase transitions. Like the separation of oil from vinegar in salad dressing left to stand, phase separation in living cells leads to the appearance of tiny blobs of proteins and other molecules, which concentrates the components needed to switch genes on and off.

Others say that the molecular collectives that regulate genes are more transient and less stable than oil droplets. ‘These are new ideas at the intersection of two established fields: namely, the physics of phase transitions of polymers and the biology of gene regulation,’ says biomedical engineer Rohit Pappu of Washington University in St Louis, US. So it’s going to take some time to figure out how they all fit together.

A complex jigsaw puzzle

Many early studies of the molecular mechanisms of gene regulation were in bacteria. Here the process seems fairly transparent and intuitive. Adjacent to genes are short stretches of DNA called promoters, which act like ‘start’ signals for the molecular machinery of transcription that binds to the DNA and produces an RNA transcript, from which the corresponding protein is made. The promoter is ‘like the beginning of a sentence’, says Tjian. Bacterial promoters tend to sit very close to their respective gene, perhaps just 100 base pairs or so apart. So the transcription machinery can track a little way along the DNA strand to find the signal that will tell it whether or not to go to work.

But in the cells of eukaryotic organisms like us, it’s much more complicated. For one thing, the regulatory machinery ‘is unbelievably complex’, says Tjian, comprising perhaps 60–100 proteins – mostly of a class called transcription factors (TFs) – that have to interact before anything happens. ‘How do you get all these pieces together?’ Tjian asks. ‘And how do they work?’

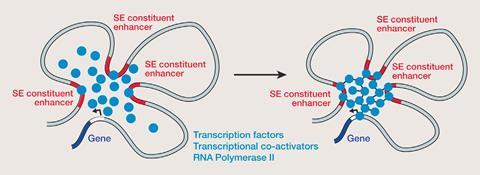

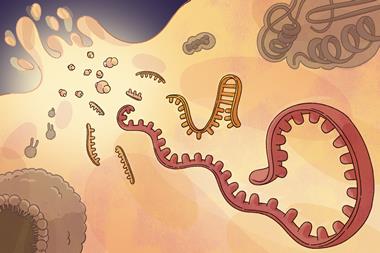

As well as promoters, mammalian genes are controlled by DNA segments called enhancers. Some proteins bind to the promoter site, others bind to the enhancer, and they have to communicate. ‘This is where things get bizarre, because the enhancer can sit miles away from the promoter,’ says Tjian – meaning, perhaps, millions of base pairs away, maybe with a whole gene or two in between. And the transcription machinery can’t just track along the DNA until it hits the enhancer, because the track is blocked. In eukaryotes, almost all of the genome is, at any given moment, packaged away by being wrapped around disk-shaped proteins called histones. These, says Tjian, ‘are like big boulders on the track’: you can’t get past them easily.

What’s more, gene regulation in eukaryotic cells depends on how this composite of DNA and proteins (called chromatin) is physically packaged within the cell nucleus. Genes tucked away within a folded-up strand of chromatin are inaccessible to the transcription machinery, and therefore inactive. Some gene activation requires distant regions of chromatin to come together – for example, to bring an enhancer site near its respective gene. Researchers postulate that this involves loops that bulge out from a densely packed chromatin strand, rather like tugging a loop out of a ball of wool, perhaps with transcription factors acting as bridges. ‘Even after 40 years of studying this stuff, I don’t think we have a clear idea of how that looping happens,’ says Tjian.

Until recently, the general idea was that the TFs and other components all fit together into a kind of jigsaw, via molecular recognition, that will bridge and bind a loop in place while transcription happens. ‘We molecular biologists love to draw nice model schemes of how TFs find their target genes and how enhancers can regulate promoters located millions of base pairs away,’ says Ralph Stadhouders of the Erasmus University Medical Centre in Rotterdam, the Netherlands. ‘But exactly how this is achieved in a timely and highly specific manner is still very much a mystery.’

Such a complex assembly of proteins and DNA should take perhaps an hour or so to form. But in 2014 Tjian and his colleagues got a shock when they looked at how long the components bind to one another– their ‘residence time’.1

‘The residence times of these proteins in vivo was not minutes or hours, but about six seconds!’, he says. ‘I was so shocked that it took me months to come to grips with my own data. How could a low-concentration protein ever get together with all its partners to trigger expression of a gene, when everything is moving at this unbelievably rapid pace?’

There’s something else puzzling too. In the early 1980s Tjian’s group carried out one of the first studies of the structure of a TF, and found it had a classic DNA binding domain based on a structural motif called a zinc finger. But it also had ‘this humungous chunk of floppy protein’, says Tjian, ‘which I tried in vain to crystallise for 10 years’. It wouldn’t crystallise because this part of the protein is inherently amorphous: it is what is now known as an intrinsically disordered domain, which has proved to be a common characteristic of many regulatory proteins (and others). These floppy regions don’t snap together into a neatly fitting interface: the interactions are rather weak, and as a result the typical lifetime of one of these protein associations is even shorter than that of the DNA binding. What’s more, the lack of well-defined structure means that the binding is rather indiscriminate – there’s no lock-and-key precision here.

In short, this association of components that seems essential for uniting a gene, promoter and enhancer to regulate transcription is an ever-changing mess of ill-fitting parts. And yet somehow it works to fix the cell reliably into a well-defined state.

Phase separation

How is that possible? This is where the notion of liquid droplets – or condensates, as they are sometimes called – comes in. The idea is that, rather than forming a precisely structured assembly, all these proteins and bits of DNA loop gather into a blob of liquid in a separate phase from the surrounding watery cytoplasm, with a high concentration of TFs.3 Then, the proteins can repeatedly bind to and unbind from one another and from the DNA, but remain in the vicinity rather than diffusing away. Their work would then be a cooperative affair involving many repeated binding events, rather like a committee reaching a decision through many conversations of its members, even though they might never manage all to sit down in the same room at the same time.

Around 2002, cell biologists Frank Grosveld and Wouter de Laat at Erasmus University came up with the concept of a ‘chromatin hub’ in which, says Stadhouders, ‘active genes and regulatory elements would cluster together in 3D space [in the cell nucleus] to ensure robust and efficient transcriptional regulation’.2

‘Liquid–liquid phase separation offers a mechanism to construct such hubs,’ says Stadhouders. ‘Such condensates provide a very intuitive and simple mechanism that enables components that need to work together efficiently to meet up and remain at a certain location for a sufficient amount of time, or to be recruited again after leaving.’ Rather than having to rely on the highly unlikely chance encounter of all the right molecules, they would have the chemical properties that make them liable to condense together into a blob, rather as oily (hydrophobic) molecules will cluster in water.

‘People speculate that condensates are created by weak interactions of a hydrophobic or electrostatic nature,’ says Stadhouders. The intrinsically disordered regions of the proteins could be vital here: they can act as sticky patches, providing weak but multiple interactions with one another that bind the blobs together. ‘It’s all wonderful in theory,’ says Stadhouders, ‘and there is some experimental evidence to support it, but it could still all be more hype than scientific fact.’

Brangwynne agrees. ‘The physical pictures that have been put forth remain hand-wavy, and to the extent that they make testable predictions, there is little or no data.’ One problem, he says, is that the heterogeneity and complexity of the cell makes it challenging to develop theoretical models of such putative liquid droplets in the way one can for simple liquid mixtures. ‘In cells the complexity of the “phase space” is astronomically larger than that seen in any non-living system familiar to soft matter and polymer physics,’ he says.

Droplet difficulties

Tjian is not persuaded that gene regulation involves genuine liquid droplets at all. The picture ‘is very appealing’, he says, ‘because it could be an answer to the question of how you get a low-concentration protein to have locally high concentration at a gene it is supposed to activate. When that idea first came about, I was quite intrigued by it.’ But that was before he started measuring the actual kinetics of the components. ‘I can’t reconcile the very rapid movement and free-diffusing behaviour of TFs with a condensate model,’ he says. ‘It just doesn’t work.’

Although droplets have been seen in studies of these regulatory proteins in vitro, Tjian thinks these don’t reflect the physiological conditions in vivo – the concentrations are often too high, say, or the salt concentration is different. What’s more, in real cells the proteins aren’t isolated but are mixed up with hundreds of others.

If condensates are as stable as everyone proposes, how do you regulate it?

Droplets have been seen in cells too. But Tjian thinks this is only when the proteins are produced in quantities much greater than are found in normal healthy cells. The matter remains in debate. Pappu and his colleagues, for example, have reported the formation of condensates of regulatory proteins in plant cells at normal in vivo levels of expression.4 However, when Tjian’s Berkeley colleague Xavier Darzacq used gene-editing tools to tune the amount of protein production, Tjian says that the ‘over-produced proteins always formed little droplets, but the others rarely ever did’.5 And if such over-producing cells were allowed to grow grow, those showing droplets would be unable to do so and would rapidly disappear.

‘This suggests to us that forming droplets was not a good thing,’ Tjian says. ‘It was stressing the cells out.’ He thinks that to rely on the formation of thermodynamically stable liquid droplets would be a bad strategy anyway for inducing the rapid events apparently involved in gene regulation. ‘If condensates are as stable as everyone proposes, the trouble is how do you regulate it?’ he asks. ‘The reason why regulation in eukaryotes requires this very dynamic and unstable situation is because you need to turn things on and off at a very fast pace. But if you have an intrinsically thermodynamically stable situation, you’re screwed – you can’t turn it off.’

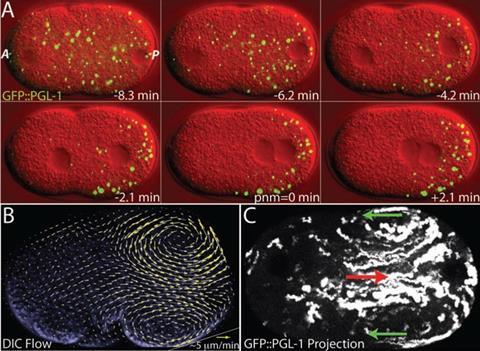

All the same, something is happening to concentrate molecules like transcription factors where they are needed. Tjian and Darzacq think that high local concentrations of the regulatory molecules can be produced in a transient and dynamic manner, which they call hubs rather than droplets. Darzacq and his coworkers recently explored in detail how this could work for the transcription factors called Bicoid and Zelda that kick off development in very early fruit-fly embryos.7 Zelda is a so-called ‘pioneer’ TF that recruits other TFs to bind chromatin and activate genes. Aside from a DNA-binding region, much of the protein consists of disordered sequences.

The researchers used light microscopy to follow the trajectories of individual fluorescently tagged protein molecules in the embryo. They found that, while the switch in the embryo state induced by these TFs takes several minutes, Zelda and Bicoid bind to chromatin only for a few seconds before detaching. These proteins seem to form hubs that are constantly changing in size and shape, like a swarm of bees buzzing around a hive. The hubs act as a focal point to concentrate other proteins so that they make brief but repeated contact with DNA, somehow collectively triggering a switch in gene activity and cell state.

Pappu thinks that there might be less disagreement here than it appears. ‘To a large extent the fixation on liquids and the erroneous designation of condensates as being simple liquids has created some of the confusion,’ he says. These condensates will certainly not be like bulk liquids formed by conventional phase separation of simple mixtures – they will, for example, be sustained by the interactions between several, perhaps many, different types of molecule, interacting in a dynamic fashion. ‘A more appropriate way to think about the constituents is as associative polymers, patchy colloids, or chimeras of the two,’ Pappu says.

He think that formation of condensates or hubs – call them what you will – might be driven by proteins with a ‘stickers-and-spacers’ architecture, consisting of units that stick together via weak, non-covalent bonds, separated by spacer units that tune the cooperativity of these interactions.8 Thus the proteins responsible have evolved to engage not (like conventional enzymes) in highly selective interactions with a given target, but in a large number of less selective ones – a completely different structural ‘grammar’. The result is not ‘liquids’ in the usual sense but what Pappu calls ‘network fluids with viscoelastic properties’. In short, they are probably a rather new and complex form of condensed matter, poised between the generic phases of conventional physics and the exquisitely tuned assemblies more familiar in biology.

Ordering on demand

‘Far from being the peculiarity it once was,’ Tjian and his colleagues wrote in a recent review,6 ‘phase separation now has become, for many, the default explanation to rationalise the remarkable way in which a cell achieves various types of compartmentalisation.’ Yet big questions still remain about how it does so, they say, and what the consequences are – and indeed how important liquid phase separation is in cells at all.

Still, Tjian doesn’t deny that it can happen in other instances; he simply warns researchers against getting too intoxicated with the idea so that it becomes a deus ex machina to account for things that might have other explanations. And indeed it seems likely that liquid droplets may be a part of the general organisational logic of the cell.9 In 2009 Brangwynne, working as a postdoc with biophysicist Tony Hyman in Dresden, reported that dense structures called P granules, containing proteins and RNA, that appear in the cytoplasm of germ cells are liquid droplets.10

‘After that, I wanted to know if this idea of liquid states of condensed biomolecules was general or not,’ Brangwynne says. ‘I started looking at the nucleolus [the region in the nucleus where protein-manufacturing ribosomes are made] and showed that it too had all the hallmarks of a liquid phase’.11 Since then there has been a flood of papers claiming to see liquid droplets in cells. The formation of membrane-bounded compartments (organelles such as mitochondria and lysozomes) is one of the main ways in which cells create the organisation needed to let their chemistry unfold in an orderly way, without cross-interference of molecular components. Liquid phase separation could provide a convenient way to produce organelles on demand and then disperse them again when they are not needed – just, for example, by increasing the activity of genes that encode blob-forming proteins. These compartment could act as storage vessels, and could help to keep concentrations of cell constituents steady even while the rate of gene expression undergoes inevitable random fluctuations: an excess of some molecules can be mopped up by dissolving in a droplet.

Concentrating proteins by phase separation might sometimes precede their condensing into solid-like structures. Brangwynne thinks this might explain the formation of the fibrous tangles of intrinsically disordered proteins that underlie neurodegenerative diseases such as Alzheimer’s. Understanding, and then blocking, the condensation process might then hold the key to therapies.

‘Liquid phase condensation increasingly appears to be a fundamental mechanism for organising intracellular space’, wrote Brangwynne and his Princeton colleague Yongdae Shin recently.12 That poses a challenge to the dominant paradigm in molecular biology over the past several decades. It suggests that, rather than building and controlling everything from the ground up, starting with information in the genes, cells have the ‘wisdom’ to accept and exploit the order that the laws of physics and chemistry offer them for free. For matters such as storage, this seems a no-brainer: nature will segregate and concentrate your molecules for you.

But it’s for ‘higher-order’ processes of cellular information processing, and especially gene regulation, that the implications of condensates become more profound. How genes interact to guide cell functions, and ultimately to enable the construction of organisms, is probably the most central as well as the most difficult problem in biology. The promiscuous and ephemeral binding of transcription factors to DNA looks like a decidedly odd and sloppy way to get precisely defined results. ‘Many of the textbooks and even our language conveys this kind of factory-floor image of what goes on inside of a cell’, says Brangwynne. ‘But the reality is that the computational logic underlying life is much more soft, wet and stochastic than anyone appreciates.’

‘Many biologists still think that while cells are made up of molecules that obey the laws of physics, concepts from physics are largely irrelevant to understanding biological organisation’ he adds. The organisational principles governing gene regulation might prove them wrong.

Philip Ball is a science writer based in London, UK

References

1 J Chen et al, Cell, 2014, 156, 1274 (DOI: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.01.062)

2 W de Laat and F Grosveld, Chromosome Res., 2003, 11, 447 (DOI: 10.1023/A:1024922626726)

3 D Hnisz et al, Cell, 2017, 169, 13 (DOI: 10.1016/j.cell.2017.02.007)

4 S K Powers et al, Molec. Cell, 2019, 76, 177 (DOI: 10.1016/j.molcel.2019.06.044)

5 I Izeddin et al., eLife, 2014, 3, e02230 (DOI: 10.7554/eLife.02230)

6 D T McSwiggen et al, Genes Dev., 2019, 33, 1619 (DOI: 10.1101/gad.331520.119)

7 M. Mir et al., eLife, 2018, 7, e40497 (DOI: 10.7554/eLife.40497)

8 J-M Choi, A S Holehouse and R V Pappu, Annu. Rev. Biophys., 2020, 49, 107 (DOI: 10.1146/annurev-biophys-121219-081629)

9 A A Hyman, C A Weber and F Jülicher, Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol., 2014, 30, 39 (DOI: 10.1146/annurev-cellbio-100913-013325)

10 C P Brangwynne et al, Science, 2009, 324, 1729 (DOI: 10.1126/science.1172046)

11 C P Brangwynne, T J Mitchison and A A Hyman, Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 2011, 108, 4334 (DOI: 10.1073/pnas.1017150108)

12 Y Shih and C P Brangwynne, Science, 2017, 357, eaaf4382 (DOI: 10.1126/science.aaf4382)

No comments yet