Improved analytical techniques mean tiny amounts of endocrine disrupting compounds or PFAS can be found in many places. But is it a problem? Anthony King talks to the scientists on both sides of the fence

-

Hormonal sensitivity: Even tiny differences in hormone exposure during early development can significantly impact behavior, physiology and health. Chemicals like bisphenol A (BPA) that mimic natural hormones are particularly concerning for their potential subtle effects on human development.

-

Detection and risk assessment: Advances in analytical chemistry have enabled the detection of extremely low concentrations of potentially hazardous chemicals. However, there is debate over the significance of these low levels, with some toxicologists arguing that traditional dose–response models are outdated and do not account for the biological impact of low-dose exposures.

-

Regulatory challenges: Traditional toxicology tests, designed to identify acute effects, may miss subtle, long-term impacts of low-dose chemical exposures. This has led to disagreements between industry toxicologists and academic researchers over the adequacy of current regulatory approaches and the need for new testing methods.

-

Endocrine disruptors: Chemicals that interfere with hormone systems, known as endocrine disruptors, are particularly contentious. The article highlights concerns about the widespread presence of such chemicals in the environment and their potential cumulative effects, as well as the challenges in assessing their risks and regulating their use.

Summary generated by AI and checked by a human editor

Miniscule differences in exposure to hormones can tweak mammals in early development, as revealed by studies of mouse pups in the uterus in the 1970s. ‘If your neighbour [in the womb] had testes, you were exposed to a little bit more testosterone than if your neighbour had ovaries,’ says Laura Vandenberg, environmental health scientist at the University of Massachusetts, Amherst in the US. Those influences had profound effects on behaviour, physiology and morphology and – in some cases – survival and health of mice, she adds.

A female with sisters as her closest siblings in her mother’s uterus tends to be more passive and attractive to males than a female located between brothers. If a female mouse is located between two males, however, she’s more aggressive and less attractive. ‘I learnt about this 20 years ago. I’m still nerding out on it,’ says Vandenberg. ‘We’re talking about part per billion or per trillion concentration differences that mammals are primed to respond to.’

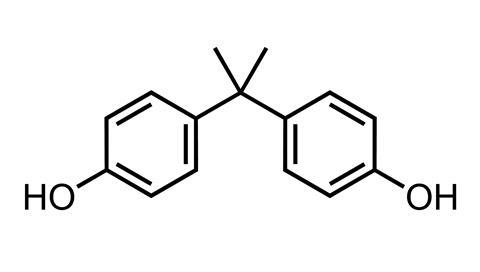

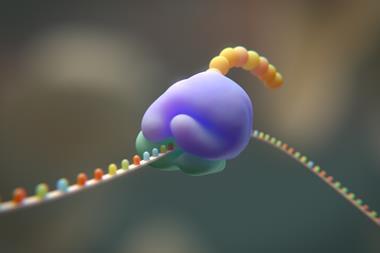

Her lab isn’t so worried about mouse attractiveness; instead, it scrutinises how chemicals can hijack the exquisitely sensitive hormone system and influence human health. Natural hormones act on embryonic and foetal tissue at concentrations equivalent to a teaspoon of water in Olympic sized swimming pools. The concern is that oestrogen-mimicking chemicals, such as the now notorious bisphenol A (BPA), subtly affect human development during vulnerable time periods. Such mimics invariably are not as potent as the natural hormone, triggering debates around cause and effect for realistic exposures.

Dose or poison

Deciding what risks particular chemicals pose and at what concentrations is the job of toxicologists and government regulators. As analytical chemistry has improved over the last decade or two, minuscule amounts of potentially hazardous chemicals have been detected in the environment and in people. ‘With analytical chemistry today, you can detect incredibly small amounts of material. But what is the effect of those amounts? Probably not much, in many cases,’ says John O’Donoghue, toxicologist and adjunct professor at the University of Rochester, US.

This capability influences public thinking around chemical exposure, he adds: ‘If something is detectable, that’s bad.’ People worry when media reports surface around a new chemical detected in, for example, their drinking water. Yet it is extremely expensive to get rid of every contaminant from water and of questionable value. Not everyone agrees with O’Donoghue; a counterargument is that the tradition of looking at parts per million is outdated and more dilute concentrations matter in biology. ‘The concept of what is low is biased because of our history of not being able to measure things,’ says Thomas Zoeller, emeritus professor of biology at the University of Massachusetts in Amherst, US. Such opposing views are passionately held.

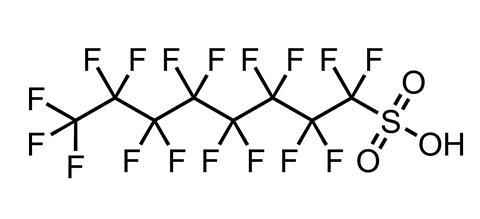

Per- and polyfluroalkyl substances (PFAS) can be detected in almost everyone’s blood and levels in the environment have reportedly been underestimated. This matters because these ‘forever chemicals’ have been linked to greater risk of kidney cancer, decreased infant growth and a suppressed antibody response in adults and children. It has taken time for action to be taken, with US manufacturer 3M recently agreeing to pay public drinking water suppliers for contamination.

It is assumed that there is a safe level. O’Donoghue says that reducing already low concentrations of PFAS in drinking water even further will prove extremely costly to governments and taxpayers. ‘It’s going to be difficult for wastewater treatment plants to meet discharge limits with today’s technology,’ says O’Donoghue about new US limits. ‘For some, the only acceptable dose is zero and for a lot of materials that is not achievable.’

Aiming for zero is pointless, according to textbook toxicology. The traditional adage accepted by toxicologists is that the dose makes the poison, attributed to Paracelsus, a Swiss physician born in the late 15th century. His philosophy remains influential. ‘There must be a threshold below which things are not toxic. If that weren’t the case, we would all be dead,’ says James Bridges, toxicologist at the University of Surrey, UK, and founder of the British Toxicology Society. Yet others see the philosophy underpinning much toxicology as ill-suited to modern times, despite a justifiable history. ‘This concept of the dose makes the poison is antiquated and should be eliminated from our vernacular,’ says Zoeller.

Reproducible regulation

Regulators began testing new chemicals in the 1950s, aimed initially at facilitating trade. These assessments required animal studies to establish a ‘no observed adverse effect level’ for a specific effect of concern. Regulators generally divide this dose by 100 to give an acceptable daily intake or reference dose that covers uncertainties and protect human society. ‘It assumes humans are always 10 times more sensitive than the test animals and that there is an additional 10 times variation in sensitivity to the response across the overall human population,’ explains James Bus, toxicologist and senior scientist at consultancy firm Exponent.

From the start, it was crucial to have tests that different countries could perform and agree on the results. ‘A lot of weight was given to how reproducible tests were and this influenced the kinds of endpoints used,’ says Olwenn Martin, environmental scientist at University College London in the UK. A typical assay might weigh and examine organs to assess effects of a chemical on cancer. Such evaluations do an excellent job of weeding out chemicals that cause immediate harm.

But environmental scientists assert that this approach creates a blind spot for more subtle, long-term effects. ‘The way we traditionally evaluated chemicals for toxicity is still based on a very old school view of what it means to be toxic,’ says Vandenberg, meaning that a test can determine a harmful dose. Meanwhile, chemicals she suspects of having more subtle effects – such as oestrogenic compounds – ignite fierce debate over what concentrations matter and what people are exposed to. This often pits industry toxicologists against academics, such as Vandenberg, who pursue new ways of investigating compounds they consider suspect.

A coterie of academics argue that traditional tests are ill suited to evaluate the biological impact of some compounds, especially those acting at vanishingly low concentrations on the hormone system. ‘With classic animal tests, we cannot necessarily say whether a chemical has an endocrine mechanism,’ says Sibylle Ermler, toxicologist at Brunel University in London, UK. It is impossible in animal tests to mirror the many chemicals and lifestyles that a human experiences over decades.

One crucial factor seems to be age of exposure. Foetuses and young babies undergo rapid development, for instance, much of it guided by hormones. ‘In classical toxicology, hormones are seen as maintaining a balance. They can be disrupted, but they they’ll return to normal,’ says Olwenn. ‘But they have a critical role in development, tuning the system and setting people on different trajectories.’ She argues that time windows of exposure for different chemicals exist and can change someone’s likelihood of developing certain conditions. BPA has been linked to impaired foetal growth in mice, as well as reduced semen quality in animal studies. Olwenn says a review of animal and human studies suggests a link to BPA and a long-term decline in semen quality in Western countries.

Back in the 1930s, BPA was recognized as an artificial oestrogen, but it only became widely used in plastics in the 1950s. It has thousands of times less affinity for the oestrogen receptor than oestradiol, the potent natural hormone, which helps to drive changes in body shape, breast development, fat deposition and brain hormone receptors. Despite being less potent, BPA is suspected of impacting the proliferation and migration of neurons in the brain. This seems contradictory, but BPA is also a ubiquitous chemical, with millions of tons made each year.

Loose receptor

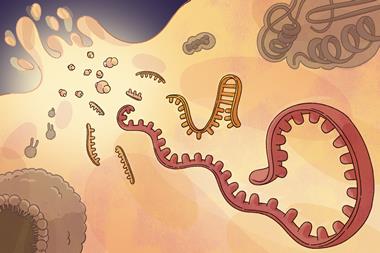

Furthermore, there are a huge number of other suspected endocrine disruptors, many of which have been identified using cell- and tissue-based assays. The reason for the promiscuousness of the oestrogen receptor lies in biology – and chemistry. Natural hormones are like a key looking for a matching lock (receptor) in the body. Some hormones and receptors are extremely specific and tough to hijack. ‘The oestrogen receptor is easily hijacked,’ says Vandenberg. ‘The space where the hormone fits in is loosey-goosey and lets all kinds of chemicals into the pocket.’ Some chemicals are poor fits, while others tend to gunk it up. The result can be to modulate the hormone system and development of the organism.

Some synthetic chemicals are suited to messing with this receptor. ‘The properties of bisphenols, phthalates and, in some cases, parabens mean they are wiggly enough to fit inside the binding pocket of the oestrogen receptor.’ Her concern is that we have created ‘a universe full of chemicals that are hijacking these same systems and inducing what look like subtle changes in early development and later on in life lead to disease’.

Even miniscule amounts of very many different chemicals will act in concert to produce adverse outcomes

A bone of contention with some toxicologists is how suspect endocrine disruptors are identified through cell assays. A Norwegian lab recently revealed that 18 out of 36 plastics from food packaging contained chemicals that activate oestrogen receptors and 14 contain compounds that block androgen receptors. The same lab previously reported an array of chemicals in plastic consumer products that caused stem cells to become fat rather than bone or muscle.

Biologist Martin Wagner at the Norwegian University of Science and Technology in Trondheim, who led this research, is concerned that ‘even miniscule amounts of very many different chemicals will act in concert to produce adverse outcomes’. He welcomes advances in analytical chemistry that are lifting the lid on just how many synthetic chemicals are in our bodies. ‘I just came back from a conference in Spain where they found hundreds of chemicals in breast milk, including all kinds of plastic chemicals,’ says Wagner.

But toxicologists can argue that detection and in vitro tests tell almost nothing about real world threats. ‘In vitro is very useful in endocrine disruptors for identifying the possibility of a hazard, but absolutely no use at all for identifying where there is a risk,’ says Bridges. ‘The big problem is that you’ve got a complex feedback system that can switch the system off.’ We have evolved to deal with many natural chemicals in our bodies, including with organs such as the liver.

It is incredibly hard to measure what levels of chemicals are in humans

The challenge is to work out how much dose would have to be given to a person to produce a response in the in vitro system, explains Bus. If this estimated dose is very much higher than what the worse-case exposure is, then it is of little concern to human health. The risk is determined by working out harmful doses and our likely exposure, a formula that regulators have codified into repeatable tests.

However, reliance on this formula annoys others. ‘It is incredibly hard to measure what levels of chemicals are in humans or conduct a human study from an ethical perspective,’ says Wagner. ‘The Achilles’ heel of chemical assessment, regulation and management is really the exposure data, and industry has exploited that weakness.’ Meanwhile, industry is not itself reporting on exposures or funding investigations, he adds.

Trust issues

Trust in industry is also an issue. An article in ProPublica revealed that 3M detected perfluorooctanesulfonic acid (PFOS) in the 1990s first in workers, then the general public, and had known from studies in the 1970s that PFOS was ‘more toxic than anticipated’ in lab animals. ‘Trust is missing between academia and industry on chemicals and specifically on endocrine disruptors,’ says Wagner. ‘They need to abandon the practice of manufacturing doubt.’

The story of BPA is one in which most regulatory agencies resisted change, before the European Food Safety Authority (EFSA) shifted gears and introduced stricter limits for food contact material in 2018. Bridges is dubious about the strength of the evidence, but given the uncertainty, the decision can be reviewed as precautionary, he adds. Zoeller notes that EFSA’s actions were based on immune effects, but the evidence for reproductive effects ‘is also quite strong’.

Industry strongly resists what it sees as any moving of the goalposts. ‘Industry and regulatory agencies say it takes 10 years to create a chemical. It gets passed and it is not fair on industry to change the landscape with new endpoints,’ says Zoeller. ‘That’s not illogical.’ Yet, in his next breath, he sets out the other side: BPA was on the market for decades and evidence began to pile up on its potential for harm. Such studies from academia put pressure on regulatory agencies, yet the nature of the evidence is rarely a slam dunk.

Regulatory agencies are playing catchup and sometimes behind the curve. ECHA, the European Chemicals Agency, is struggling to assess all new chemicals. ‘In principle, each new chemical should be assessed before it’s on the market,’ says Ermler, who estimates that a minority of chemicals have been fully assessed. Rarely do regulators reduce allowable exposures of a chemical or take a chemical off the market without the input of academic studies and public pressure.

Regulatory remedies

There are signs that the differences between regulatory toxicologists and academics can be bridged. Ermler is working on new tests for chemicals that might disrupt the thyroid system, with potential to impact neurodevelopment of foetuses and reduce IQ in children. Her lab is part of an EU-funded project (Goliath) seeking to develop an assay based on differentiation of stem cells to test for effects on adipose tissue with relevance for metabolism and insulin resistance.

Approaches in academic labs are often unsuitable for standardised tests, however. Researchers pursue new techniques to make discoveries about chemicals and potential mechanisms to generate publications and attract funding. When EFSA proposed reducing the acceptable daily intake of BPA by a factor of 20,000, says Zoeller, ‘almost every regulatory agency – including the European Medicines Agency and US FDA [Food and Drug Agency] complained that that they’re using data from academic labs. They want to keep that out.’

There’s a problem of disciplines being siloed

Goliath aims to bridge the gap and develop regulatory tests for endocrine-disrupting chemicals. Emler says that a ‘weight of evidence’ approach is one strategy that could work. This would look at all the evidence to judge whether a chemical is a suspected endocrine disruptor.

Vandenberg argues that more tests from academia should be introduced. They are avoided because some are complicated, or require complex skills. For many scientists it would be far better if red flags were raised during the development of chemicals, not afterwards. Many believe that replacing BPA with other similarly structured bisphenols was not safer for consumers, for example.

Martin says that while material scientists view BPA and phthalates as problematic, ‘some have no comprehension of the diverse universe of chemicals we’re talking about, and that we know so little about their toxicity’, adding there is little if any toxicology taught in chemistry degrees. ‘There’s chemistry and there’s biology,’ she says. ‘There’s a problem of disciplines being siloed.’ Instead of yet more varieties of PFAS, she believes there is room for truly innovative chemistry. Others complain that there is little incentive for companies to develop safer chemicals to replace suspect ones.

Yet there may be a societal need. ‘People born in the 60s and later are experiencing, for the first time, a steep increase in the risk of cancer at almost every site,’ says Cohn. Between 2022 and 2050, cancer cases have been projected to rise from 10 million to 19 million. Cohn believes chemicals have a role. She calls for the green chemistry movement to take up the challenge and avoid chemical structures with characteristics associated with harm. ‘This isn’t about stripping away modern life. This is about trying to be a little smarter about what we do,’ says Cohn. ‘Change is difficult. The questions to be asked is, is the change worth it? That’s a public and a political question.’

Anthony King is a science writer based in Dublin, Ireland

No comments yet