Nina Notman explores some of the latest scientific approaches skincare companies are using in the quest to develop high-earning anti-ageing cosmetics

A focus on skincare is nothing new. I bet I’m not alone in having memories of my grandmother sitting at a dressing table, plastering a succession of lotions on her face. Even further back, there is evidence of plants and their oils being used as cosmetics in Roman times.

Today, the global skincare market is worth several billions pounds a year and, in an attempt to gain (or maintain) a share in this lucrative business, companies are constantly on the lookout for ways to stand out from the crowd. Borrowing techniques developed by the pharmaceutical industry is one increasingly well-trodden path to success.

A genetic focus

Geneu, a start-up company based in London, UK, is taking a lesson from personalised medicine, and claims it can tailor its skincare products to match each client’s unique genetic makeup. The company, co-founded by Imperial College London engineering professor Christofer Toumazou, refers to this as personalised skincare. A swab of cheek cells is taken from each client and two of their approximately 24,000 genes are analysed using the polymerase chain reaction.

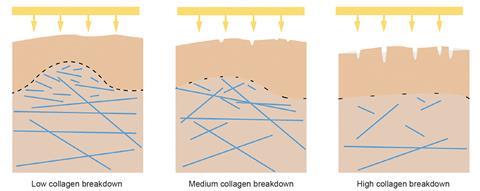

‘We’re focused on two particular genes which we feel have the biggest impact in terms of how your skin is going to age,’ explains Geneu’s chief executive Martin Stow. ‘One of the genes is associated with a matrix metalloproteinase enzyme that breaks down collagen. There’s a lot of evidence to show that if you have larger quantities of this enzyme, you’ll be a fast degrader of collagen and you’re more likely to see the signs of ageing – things like fine lines and wrinkles – earlier,’ he says.

‘The second gene we look at is an antioxidant protection gene, involved in a pathway which neutralises free radicals,’ Stow says. ‘There’s a lot of evidence to show that free radicals can cause skin damage and the gene we look at is associated with how good your body is at neutralising those free radicals,’

The company then uses this genetic information, along with lifestyle details such as frequency of sun exposure and whether you smoke or not, to prescribe two serums to be used concurrently morning and night. ‘One serum is related to collagen breakdown and the other to antioxidant protection,’ explains Stow.

These serums don’t contain anything new in terms of active ingredients. Where the novelty comes is in the claim to match the active ingredients, and their concentrations, with the very specific needs of each client.

Geneu launched two years ago and has a growing string of endorsements from lifestyle journalists and celebrities. It has also conducted a 12-week trial at Imperial of 86 men and women of various ages, which has not been published. ‘We found 81% saw over 12 weeks an improvement in their facial appearance and 71% actually saw a reduction in the appearance of fine lines and wrinkles,’ says Stow.

He says that what attracts customers the most, however, is the company’s scientific dialogue. Customers are given their genetic results and prescriptions by staff with degrees in either molecular biology or genetics. ‘I think that gives us quite a lot of credibility because the discussion is scientific as opposed to sales based,’ says Stow.

The advisor who sent me my results, for example, is currently also working towards a PhD in cell and molecular biophysics at King’s College London. I was trying out the company’s recently launched postal service. A swab was posted to my home, wiped around my mouth for just over a minute and then returned to the company’s labs along with a completed lifestyle questionnaire. A few days later a description of my genetic results, and suggested serums to purchase to best care for my skin, appeared in my inbox.

First, the report stated that my collagenase enzyme ‘performs at a faster pace [than average], meaning I am predisposed to a prolific breakdown of collagen’. In contrast, my antioxidant protection enzyme – the one that you want to be highly active – is not, which apparently leaves my skin prone to free radical attack. How skin ages is not completely predetermined by the genes we are born with, however, so it was at least good news that my lifestyle had been deemed healthy. The overall message of course is that their serums could help save me from my genetic destiny.

Demographic dividend

While Geneu are offering a highly personalised, high-end product based on the analysis of an individual’s genes, other more established cosmetic companies are looking to genomics to allow them to recommend lower priced, customised skincare regimes to women based on their age and ethnicity.

‘There are two obvious important ways that genetics plays a role in how people age over time,’ explains Alexa Kimball, a professor of dermatology at Harvard Medical School, US, who is currently collaborating with global skincare brand Olay. ‘The first is, what genes are you born with and does that give you protective or non-protective effects? There’s been a lot of interesting research recently along those lines. The second area, which is what we were focusing on, is what genes get turned on and turned off as you age, and are those patterns predictable and are they manageable or reversible in some way?’

Genomics has been a key focus of Olay (owned by Procter & Gamble) for more than a decade, explains one of its principal scientists Frauke Neuser. ‘It’s a great complementary approach to everything that we can measure from the outside, such as skin appearance, skin moisture and elasticity. It’s really building a much more complete picture of what’s going on inside your skin.’

The current collaboration is a looking at how the expression of genes related to ageing change in the skin of women in different decades of their life, ranging from their 20s to their 70s, and from four different ethnic groups. For each participant, full thickness skin samples are being collected from sun-exposed (such as the face) and non-sun exposed (the buttock) areas to allow the impact of UV light to also be considered.

It is the largest study Olay has run to date; they are about halfway through testing and over 230 women have participated so far. Some of the results have already been analysed and presented. ‘We have been able to look at how the genes that are being regulated change over time. You can clearly see the shifting in gene expression over decades. Certain genes that have been regulated when you’re younger start to turn off and slow down as you get older. You can see that pattern very distinctly,’ explains Kimball.

To further support these conclusions, the team has looked at a population of women coined exceptional agers: those who looked younger than their age. ‘We could see that their gene expression patterns mimicked people who actually were younger. The things that continued to make them look youthful were in fact the same things that were found in the youthful group,’ Kimball says.

Certain genes start to turn off and slow down as you get older

‘That’s helpful [from a product development viewpoint] because that starts to say, “If you can capitalise on those pathways you may be able to preserve appearance and slow down that ageing process over time by exactly targeting those pathways”,’ she adds. Once the pathways that you’d want to either preserve, escalate or deescalate have been identified, the next step would be to test ingredients against those pathways in the lab to identify those that might be particularly helpful in slowing the ageing process.

‘The results also suggest that women who are in their 50s might need different ingredients and different skincare products to women in their 30s or 70s, to compensate for different changes that we can predict are going to occur at different times. It’s kind of a step before you get to personalised medicine to say, “We can customise in a much more precise way what we should be building into these products for different age groups”,’ Kimball explains.

Ethnicity is also being assessed in detail to see how it influences the stage in a woman’s life when changes in the expression of genes related to ageing occur. For example, it is well known that in general African–American women’s skin appears to age more slowly than that of Caucasian women, but what is going on genetically to control this has not previously been understood. Blood samples have also been taken from the trial participants and analysed by US-based gene profiling firm 23andMe to ensure the women have self-assessed their ethnicity correctly.

The genomic analysis for this study is being carried out using DNA microarrays – a well-established piece of kit. The bigger challenge has been the data processing. ‘You get terabytes of data out of these genomic analyses, and you need the right expertise to not only capture the data but make sense of it. It is a very big undertaking,’ explains Neuser. Olay has built up its bioinformatics expertise though earlier projects not just in skincare, but also oral care and deodorant.

Improved ingredients

It isn’t just genetic and genomic analysis approaches that the cosmetics industry is looking to copy from its pharmaceutical counterpart. In January 2016, the skincare arm of chemical giant BASF announced a collaboration with the French contract research organisation Cytoo. The team has repurposed cell screening technology typically used in early-stage drug discovery to screen active ingredients for an ability to increase skin firmness.

BASF is a raw materials supplier, so instead of selling cosmetics directly it supplies active and non-active materials that companies such as Geneu and Olay use to formulate consumer products. Together, Cytoo and BASF have developed a high throughput screening method, called Fibroscreen Flex, for assessing the impact of compounds on the contractibility of fibroblast cells found in the skin’s dermis layer. ‘Skin firmness and the reverse, skin sagging, is an indicator of age. Fibroblasts are responsible for 95% of the process of skin losing its firmness and elasticity as we age, so that’s why we take care of fibroblasts in our cosmetics,’ explains BASF project manager Valerie Andre-Frei.

Fibroblasts, whose roles include collagen synthesis, are a common target for anti-ageing ingredients, with retinol (vitamin A) probably being the most widely known. ‘Our challenge is to be better than the last generation,’ Andre-Frei says. One aim of the current project is to find an ingredient with better performance and efficiency at a lower concentration than those currently on the market. ‘The consumer would like to see immediate results, so it’s desirable to have products that are efficient in a shorter period of time, say after 15 days or one week,’ says Andre-Frei. There is also a desirability to develop injectable fillers with longer lasting results. The current collagen and hyaluronic acid fillers last between a few months and a few years.

‘Fibroscreen Flex is a cell-based assay which evaluates dermal firmness,’ explains Mathieu Raul, Cytoo’s director of business development. ‘The platform mimics the in vivo dermal stiffness allowing the culture and testing of fibroblasts in a physiological environment.’

Each assay is comprised of a micropatterned soft deformable substrate coated with collagen, which mimics the dermis. When fibroblast cells are cultured on these assays, the natural contractility of the cells causes the surface – and therefore the visible pattern – to deform.

The assays are then screened against a library of potentially active compounds. Those compounds that cause the fibroblasts to relax allow the micropattern to return to its original shape, whereas those that cause cell contraction will further deform the soft substrate and therefore the micropattern. The latter is the result the team were looking for. ‘We have worked together with Cytoo for two years to develop the method and then develop the product,’ explains Andre-Frei. ‘This product will launch this year.’

BASF launch around eight new skincare products a year, and three years is a typical turnaround time to take a totally new ingredient from project initiation to market. And it isn’t just the pharma industry’s screening methods that BASF is looking to repurpose for speeding up and improving skincare development. ‘We are always looking into what technology is developed for pharma and whether it’s suitable for re-applying to skin cells. We like to do this because the methods will already be very well developed and standardised and so on,’ says Andre-Frei.

Skincare companies also look to current societal and pharma trends for fundamentally different ways to tackle skin ageing too. BASF is currently looking at whether two big buzzwords in pharma – microbiota and epigenetics – can be repurposed for skincare, says Andre-Frei. Meanwhile, Olay are doing a lot of work in proteomics. ‘We are looking at how different proteins in skin act as biomarkers of certain conditions: moisturisation, skin health, ageing,’ says Neuser.

‘Our strategy to is to have a lot of very upstream work that doesn’t have a direct link to a brand, which is more about understanding every aspect of skin, and at some point we’ll then move into the more branded content. At the beginning, it’s all about fundamental understanding down to every level we can think of, whether it’s proteomics, genomics, genetics. Then making sense of all of that.’

Nina Notman is a science writer based in Salisbury, UK

No comments yet