Exploited unknowingly by craftsmen for hundreds of years, the plasmonic effects of metal surfaces have rapidly gone from curiosity to treating cancer. Andy Extance trips the light fantastic

One day in 1989, when working at the NEC Research Institute in Japan, luck paid Thomas Ebbesen a visit that he would not fully understand for almost a decade. ‘I was trying to control molecules’ radiative properties by putting them in tiny holes in a gold film,’ he recalls. ‘I found that the hole array alone transmitted light more efficiently than accepted theory at the time predicted. A lot of people didn’t believe me.’ That was until 1996, when he met theorist Peter Wolff, who specialised in electronic behaviour in metals, and who had then joined NEC. Wolff realised the probable cause of the phenomenon that became known as extraordinary, or enhanced, optical transmission (EOT): surface plasmons.1

Surface plasmons arise when metal surfaces trap light (see final section below). They can be short-lived, as defects in the metal can easily trigger the loss of the light’s energy as heat and extinguish them. Though the holes in Ebbesen’s foil were smaller than the wavelength of the incoming light, plasmons travelling along one surface emerged on the opposite side as photons. He realised this could be a powerful new way to collect, focus and manipulate light. But to use it researchers would have to develop chemical and physical processing techniques that created smooth, uniform metal surfaces with suitable nanometre-scale dimensions.

Artists and craftsmen have unknowingly made use of plasmons for at least 1600 years, by colouring glass objects with metal particles (such as the Lycurgus cup; see below). In the 19th century, Michael Faraday systematically studied the synthesis and appearance of colloidal gold. But researchers didn’t identify their underlying colour-controlling surface plasmonic principles until the 1950s. At first, interest centred on intense electromagnetic fields associated with surface plasmons. As the fields’ properties depend upon the environment near a metal surface, adsorption of small molecules causes detectable changes, which were soon exploited in surface plasmon resonance spectroscopy. These electromagnetic fields also enabled single-molecule sensitivity in surface-enhanced Raman scattering spectroscopy (SERS).

On target

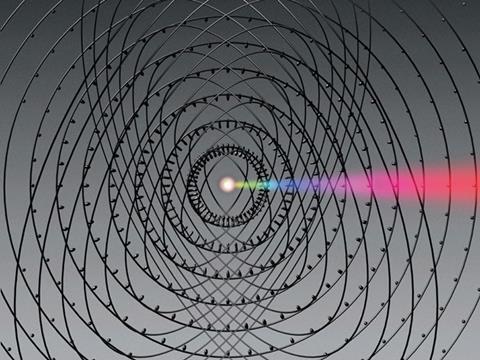

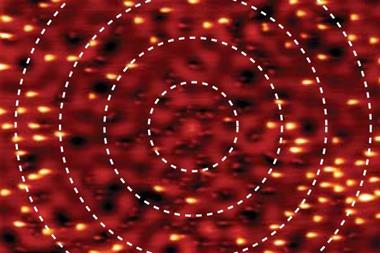

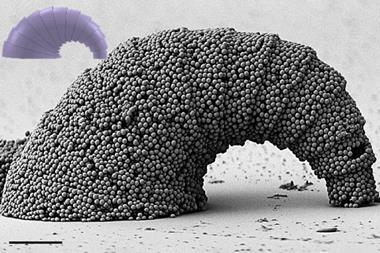

EOT showed researchers a hint of surface plasmons’ full potential – and that they had the technology to control them. ‘People realised that if you structure the metal well, you could engineer plasmons,’ explains Ebbesen, who is now at the University of Strasbourg in France. Nanostructures could readily be made by modern ‘bottom up’ techniques evolved from Faraday’s or ‘top down’ techniques like focussed ion beam (FIB) milling, where streams of Ga+ ions pattern metal surfaces. In one early example, Ebbesen and his colleagues extended the FIB milling approach they used with the hole arrays to make bullseyes on silver films.2 ‘The bullseye is a single hole with concentric rings around it that act like an antenna,’ Ebbesen says. ‘The grooves’ shape and periodicity provides the right conditions to trap many waves at the surface, so the structure transmits ten times more light through the hole than actually hits it.’

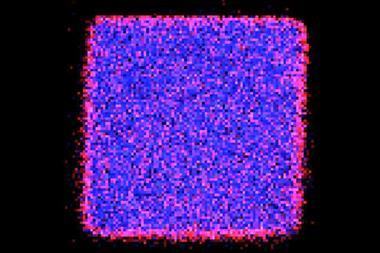

Today, hole arrays and bullseyes can enhance sensitivity in applications like SERS and fluorescence correlation spectroscopy, which is used to study complex mixtures of biomolecules. They can boost sensitivity by magnifying the intensity of both the incoming light and that emitted by molecules. But top-down techniques like FIB milling and electron-beam lithography aren’t suited to making such structures on a larger scale, notes Teri Odom from Northwestern University in Illinois, US. ‘E-beam lithography is a nice tool for controlling resolution and reproducibility with features down to about 10 nm,’ Odom says. ‘It’s very good for prototyping, but it can take over 24 hours to produce a structure with a 50 µm x 50 µm area, so it’s not a massively parallel approach. This aspect of nanostructure fabrication is important for the future of plasmonics: if you cannot scale structures uniformly and with high fidelity, then you can’t really exploit them for any practical usage.’

Odom’s team has therefore devised more scalable techniques, based on ‘soft nanolithography’. In a typical example, they fabricate silicone rubber moulds from a patterned silicon master. They then use these moulds to create patterns in polyurethane or photoresist materials from which they can ultimately produce nanostructures like metal hole arrays.3 This technique is extremely scalable, cheap, and accessible, she says, but could still be improved. ‘Sometimes feature-to-feature uniformity is not as high as more expensive lithographic tools,’ Odom concedes.

Bottom up

The basic approach to chemically synthesising plasmonic metal structures gradually reduces a soluble metal salt to form and grow pure metal nanoparticles. ‘Then we use capping agents that bind to the metal surface and stop particle growth,’ explains Luis Liz-Marzán from the University of Vigo, Spain. ‘These capping agents very often also direct growth, and manipulate the morphology of the particles.’ That ability is critical, he says, as metal surfaces’ plasma oscillations, and therefore their optical properties, depend upon size and shape. For example, gold’s usual appearance gives way to a blue colour when light is shone through a thin film of it. Gold particles can also be blue but acquire several tones of purple, through to red and orange as particle size reduces to 3 nm.

BBInternational, based in Cardiff, UK, produces thousands of litres a year of such vibrant red spherical gold particles for analytical testing, according to Pete Corish, the company’s head of business development. It predominantly provides them conjugated to antibodies for lateral-flow diagnostic assays. In this application, the gold nanoparticles are carried along membranes in sample liquids containing molecules to be detected by capillary action, providing a potent visual indicator. Arguably this is most familiar in pregnancy tests and, although these usually exploit coloured latex particles, most other assays exploit gold colloids’ red appearance.

BBInternational is now working on alternative particle shapes. ‘While BBI has made its name in spherical gold nanoparticles, it is looking to develop more plasmonically active particles, such as rods,’ says Corish. These could be used in ‘plasmonic shifting’ assays, he suggests. ‘You can take molecules that bind to each other and label each of them with metal nanoparticles. As they’re brought close together, their plasmons interact and generate a measurable change in signal.’

Changing particle shape is a particularly effective way to tune their plasmonic behaviour, Liz-Marzán says. ‘Go from a 5 nm to a 50 nm sphere and the resonance wavelength changes very little,’ he explains. ‘Go to an ellipsoid which is 5 nm in the short axis and 10 nm in the long axis, and you can get a much larger shift.’ Consequently, much research over the past decade has looked at the plasmonic properties of differently shaped nanoparticles.

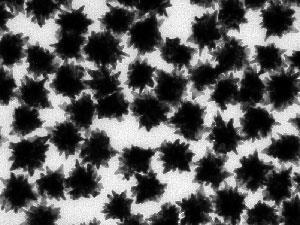

For example, Liz-Marzán’s team has made gold nanostars with ‘extremely attractive’ optical properties.4 To do this, the aim is to create environments where particles grow at differing rates according to their crystallographic directions – but the researcher warns it’s not yet an exact science. ‘The facets have different surface energies,’ he says. ‘In theory, we can use that to decide where our capping molecules go and direct the growth. Unfortunately, this is not the case in practice. Most of the understanding we have comes from looking at the result and then trying to rationalise what happened in the reaction. Predicting the nanomaterial’s morphology is still a really big challenge.’

Shining light

When surface plasmons are not being used to transport light, their loss of energy as heat can sometimes be beneficial. Nanospectra Biosciences, based in Houston, Texas, injects nanoparticles into cancer patients’ bloodstreams, from where they embed themselves into fast growing tumours. Near-infrared light pointed at the tumour can penetrate the skin and couple with plasmon resonances in the particles, which generates heat and kills cancer cells without harming surrounding healthy tissue.

‘Light can interact strongly with the collective electron cloud oscillation outside the observed particle boundaries,’ explained Glenn Goodrich, vice president of process development and chemistry at Nanospectra. ‘That means they collect light from a volume that is larger than the physical particle size.’ This approach is in phase I clinical safety trials for prostate cancer in the US and head and neck cancer in Mexico, and Goodrich is positive about the outcome. ‘There have been no negative toxic effects reported from any of the patients we treated,’ he says.

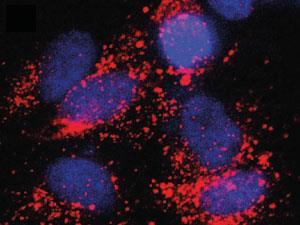

Odom is also keen to bring plasmonics to medicine, but would rather avoid the risks of damaging the surrounding tissue by heating. Instead, her group has developed a highly targeted potential cancer treatment by attaching DNA aptamer molecules to gold nanostars. ‘The aptamers are both a targeting ligand for a protein surface receptor and a drug,’ she explains. The surface protein binds to the aptamer and then shuttles the aptamer–gold nanoconstruct directly to the cell nucleus. This mechanism was tested in both ovarian and cervical cancer cell-lines.5

In the next step, the nanostars strongly absorb the near-infrared laser light that Odom’s team shines at them. The laser only shines in femtosecond bursts, so heating is avoided. The pulsed light cleaves the thiol bond attaching the aptamer to the gold nanostar, thereby releasing it to attack the cancerous cell. ‘We believe that the release happens predominantly at the points of the stars, where the electromagnetic fields are concentrated,’ Odom says. The solution-phase synthesis her team uses to make the nanostars is biocompatible and scalable, she adds, although such methods do not produce completely uniform nanostar shapes. ‘The main drawback in synthesis is that none of the particles are identical,’ she says. ‘They look close, but they’re not quite the same.’

Controlling chemistry

Reliable manufacturing is also important to Goodrich, who has to produce spherical particles, but not of pure metal – Nanospectra has moved on to core–shell particles to achieve the desired absorbance. ‘The particle is a solid silica core with a 10–30 nm gold shell,’ he says. ‘They have a plasmon resonance on both the outer and inner shell boundaries. Those resonances interact, which we can use to tune the wavelength by changing the film thickness.’

Nanospectra’s production still relies on reducing dissolved gold ions to produce the shell, however. ‘The main challenge is reproducibly controlling shell thickness, making it uniform, smooth and continuous, rather than a series of gold islands,’ Goodrich explained. ‘The sharpness of the plasmon resonance depends on how smooth the film is.’ When it comes to scaling up, the degree of difficulty in making a reproducible process is amplified, he adds. ‘Making 10 ml of nanoshells, is it really that difficult? Making 100 litres of nanoshells at a time brings a whole other set of problems in getting a uniform product every time.’

To meet regulations intended to ensure bioassays are reproducible, BBInternational currently has to ensure that the diameters of its gold nanoparticles vary by no more than 5%, Corish notes. ‘For the future of plasmonic based bioassays incorporating these new anisotropic particles, the reproducibility, scalability and manufacturability has yet to be addressed to those sorts of tolerances,’ he says. ‘It is one thing to observe physical phenomena in the lab, and another to take that technology and convert it into a commercial reality. People are still getting to grips with what these materials can do, how they can be applied – and when they do, they will still face the challenge of scaling up – but we will get there.’

With plasmonics now well enough established for such scaling and consistency issues to become important, Ebbesen is now moving on to exploit it in an exotic new field.6 ‘We use the strong electromagnetic fields associated with surface plasmons to couple them to molecules and to make hybrid light–matter states,’ he says. ‘If you have two atoms and you exchange electrons rapidly, you get two molecular orbitals. Similarly, by exchanging photons between a molecule and a plasmon very rapidly, two new hybrid states can be created. Putting molecules into the surface plasmon’s environment changes the molecules’ properties, from colour to chemistry,’ he says. ‘We have already changed the yields and rate of a chemical reaction.’ And if such states live up to the promise of Ebbesen’s early results, plasmons could bring new horizons to reactions we thought we knew intimately.

Surface plasmons: Surprisingly familiar quasiparticles

Much as the particle comprising a quantum of light is called a ‘photon’, a ‘plasmon’ is a quasiparticle comprising a quantum of wave-like ‘plasma oscillations’ in electron distribution. The name alludes to plasma environments, where free-floating ions and electrons can readily form such alternating regions of positive and negative charges. However, these charge waves – and their associated powerful electromagnetic fields – are more easily used when travelling through electrons at metal surfaces, where they are known as surface plasmons.

When light reaches the metal’s electron cloud in the right circumstances, it can be trapped to form a surface plasmon. The light induces a dipole that oscillates in phase with the electromagnetic field of the incoming light. If that light has a longer wavelength than the plasma oscillations characteristic of the metal on which it falls, then it is reflected, while shorter wavelengths are absorbed or scattered. Gold and copper’s distinctive colours are down to surface plasmons in the visible range. Colours from plasmonic excitation of small metallic particles in glass have also long been used in stained glass windows and prized artefacts. For example, the Lycurgus cup, a greenish glass goblet from 4th century Rome held in the British Museum, looks red when a light source is placed inside.

References

1 T W Ebbesen et al Nature 1998, 391, 667 (DOI: 10.1038/35570)

2 H J Lezec et al Science 2002, 297, 820 (DOI: 10.1126/science.1071895)

3 J Henzie et al Nat. Nanotechnol. 2007, 2, 549 (DOI: 10.1038/nnano.2007.252)

4 P S Kumar et al Nanotechnology 2008, 19, 015606 (DOI: 10.1088/0957-4484/19/01/015606)

5 D H M Dam et al ACS Nano, 2012, 6, 3318 (DOI: 10.1021/nn300296p)

6 J A Hutchison et al Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2012, 51, 1592 (DOI: 10.1002/anie.201107033)

No comments yet