The creators of metal–organic frameworks (MOFs) have been awarded this year’s Nobel prize in chemistry. The Nobel committee noted that their work in this area had provided chemists with new opportunities for solving some of the challenges we face, with researchers now using them to harvest water from desert air, extract pollutants from water and capture carbon dioxide.

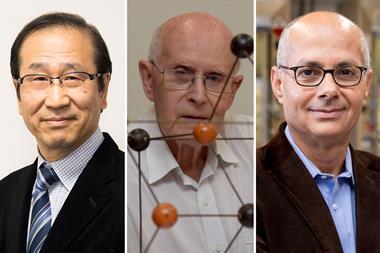

The 2025 Nobel prize in chemistry was split equally between Susumu Kitagawa, at Kyoto University in Japan, Richard Robson, at the University of Melbourne in Australia, and Omar Yaghi, at the University of California, Berkeley in the US, ‘for the development of metal–organic frameworks’.

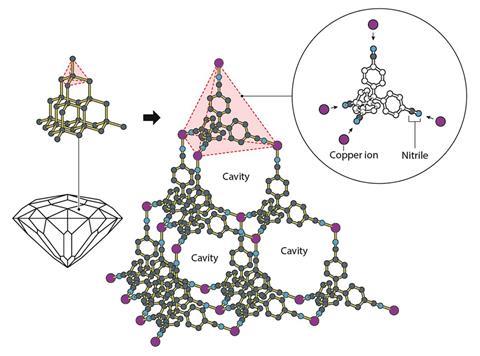

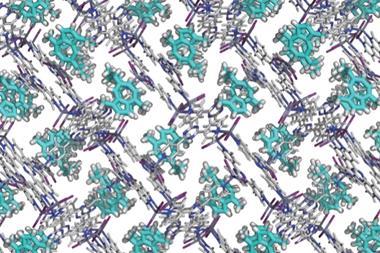

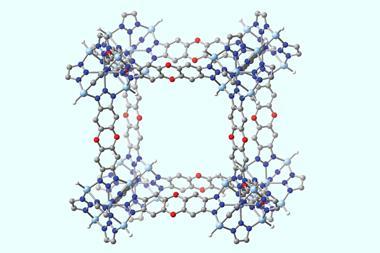

It was Robson who first reasoned it would be possible to make these frameworks in the 1980s. Inspired by diamonds, Robson build a similar structure based on positively charged copper ions. The copper ions were combined with an organic linker that had four groups, each with a nitrile at the end, that was attracted to the copper ions. He found that they organised themselves into a large molecular construction – like the carbon atoms in a diamond. However, unlike diamond, this structure contained a lot of large cavities.

He published his work in1989 in the Journal of the American Chemical Society suggesting that this could offer a new way to construct materials, and he went on to present several new types of molecular constructions with cavities filled with various substances, using one of them to exchange ions. However, many of them were unstable and collapsed easily.

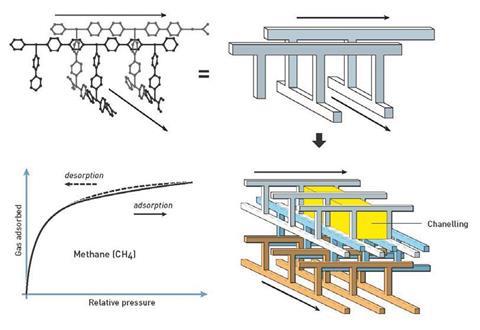

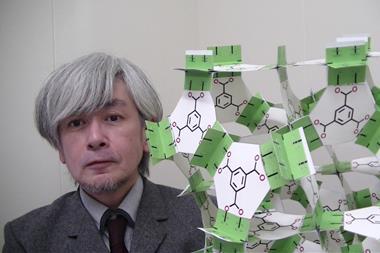

In the early 1990s, Kitagawa was also experimenting with molecular construction and, in 1997, he had a breakthrough – using cobalt, nickel or zinc ions and a molecule called 4,4′-bipyridine, his research group created 3D MOFs intersected by open channels. When this structure was emptied of water, it remained intact and could even adsorb gases, including methane, nitrogen and oxygen, in a reversible way, without changing shape.

In 1998 he set out his vision for MOFs in the Bulletin of the Chemical Society of Japan, highlighting their enormous potential, and reasoning that they could also form soft, flexible materials that would change shape on changing the conditions.

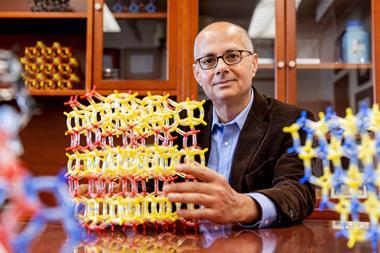

In the US, in 1995, Yaghi published the structure of two different 2D materials that were like nets and held together by copper or cobalt. The cobalt structures could host guest molecules and were so stable they could be heated to 350°C without collapsing. It was at this point that he coined the term ‘metal–organic framework’ when he published his work in Nature.

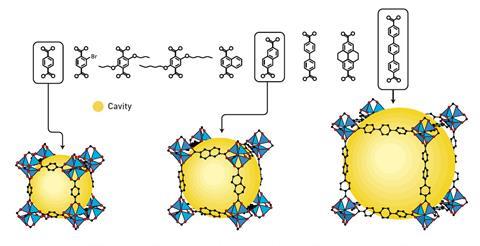

In 1999, he established the next milestone in the development of MOFs when he presented MOF-5, an exceptionally spacious and stable molecular construction that, even when empty, could be heated to 300°C. The internal structure of this MOF is so large that just a couple of grams has a surface area the size of a football pitch.

In 2002 and 2003, Yaghi published in Science and Nature respectively, showing that it was possible to modify and change MOFs to give them different properties. To highlight this, he produced 16 variants of MOF-5, with cavities that were both larger and smaller than those in the original material.

Since then, researchers have created numerous different, functional MOFs and many companies are now investing in their mass production and commercialisation.

Speaking at the press conference to announce the winners, Olof Ramstrom, a member of the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences and Nobel Committee for Chemistry said: ‘Through these fundamental breakthroughs from our laureates, and continued efforts in the field, this has led to a very, very rich and active area where we see new MOFs developed almost every day. And many of these frameworks have also been applied … and it’s very, very clear that we will expect many more frameworks to be developed and many more applications in the future for the benefit of humankind’.

Responding to the news of his award, Kitagawa said: ‘I am deeply honoured and delighted that my longstanding research has been recognised’.

Annette Doherty, president of the Royal Society of Chemistry offered her congratulations to all three researchers on ‘this well-deserved recognition’. ‘Your work reflects the best of what chemistry can do: connecting people, ideas and discoveries to change the world for the better,’ she said. ‘Metal organic frameworks are an incredible group of materials, which have fantastic potential in a range of applications – from gas storage and separation to carefully targeted drug delivery and even removing pollution from the environment.’

‘Every year we see Nobel prizes given to chemists who welcome the challenge of finding solutions to the biggest problems our global society faces – better healthcare, environmental protection, clean energy, and secure food and water for everyone. This year’s winners are a great example of that endeavour.’

No comments yet