Ruling that Regeneron’s Praluent antibody infringes Amgen’s Repatha patent could stifle innovation

There has been a surprising turn in the long-running US patent infringement litigation between Amgen and Regeneron–Sanofi over their cholesterol-lowering PCSK9 inhibitors Repatha (evolocumab) and Praluent (alirocumab). The Federal District Court judge, Sue Robinson, has decreed that Praluent should be removed from the market altogether. The decision follows a jury ruling in March 2016 that Amgen’s patents are valid, and Praluent infringes them.

Robinson said the court was ‘between a rock and a hard place’. She found several factors that favoured an injunction on Praluent’s sales, while admitting that public interest would be impaired by removing a useful drug from the market.

When something is really complex, it is very difficult to describe it with the accuracy that patent claims require

The judge permitted Sanofi and Regeneron to appeal the injunction in the 30 days before it takes effect. She also encouraged the two sides to work towards a solution in the interim. While this appeal will be settled by mid-March, it will likely take another year before the full appeal on the patent decision is concluded.

‘It was pretty shocking,’ says Jacob Sherkow from New York Law School, US. He cites just two examples in the past couple of decades where a permanent injunction has been handed down – Roche’s competitor product to Amgen’s Epogen (epoetin alfa), and Insmed’s rival to Tercica’s Increlex (mecasermin). There are hundreds of patent infringement suits filed every year, he says, and while the patent owner often prevails, the normal remedy is financial, with the infringing product allowed to remain on the market.

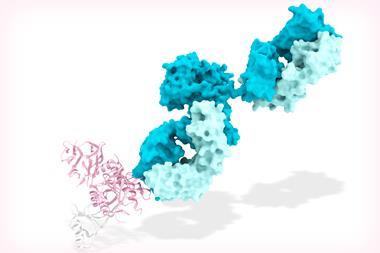

Patents on antibody drugs are not as straightforward as those on small molecules, making for complex litigation. ‘You have to figure out a way to describe an inordinately complex molecule in the language of patent claims,’ Sherkow says. ‘You can’t sufficiently describe an antibody by going through every atomic interaction in a multi-kDa compound. The way patent attorneys have traditionally claimed antibodies is by describing some combination of the species from which it was derived, the antigens that bind to the antibody, and sometimes a genetic sequence that would give rise to the antibody if it were translated. When something is really complex, it is very difficult to describe it with the accuracy that patent claims require. We have had antibody patents for more than 30 years, but the law is still not completely settled.’

Companies don’t want to spend a huge amount of money developing a drug, and then get sued for patent infringement and find they can’t sell it

According to Matthew D’Amore, intellectual property partner at law firm Morrison & Foerster, the decision strengthens the hand of patent holders, and may encourage more innovator-versus-innovator cases. ‘Assuming it’s upheld, the decision provides a roadmap to the evidence that might support the grant of an injunction in such a case, while also recognising that the public interest is a significant countervailing factor,’ he says.

Benjamin Roin from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology Sloan School of Management, US, agrees that we are likely to see more such cases in future, which may impact innovation. ‘The problem is that [companies] don’t want to spend a huge amount of money developing a drug, and then get sued for patent infringement and find they can’t sell it,’ he says. ‘Unlike generics, you cannot challenge the patent ahead of making a big investment in development. It’s possible that this will discourage other entrants on that target.’

No comments yet