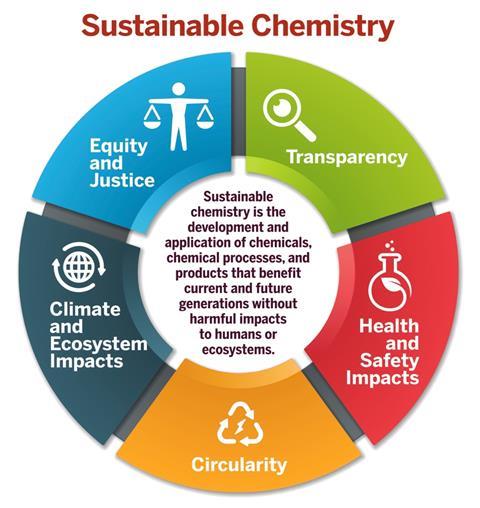

Sustainable chemistry should be defined as ‘the development and application of chemicals, chemical processes, and products that benefit current and future generations without harmful impacts to humans or ecosystems.’ That’s the outcome of a working group tasked with developing a robust and actionable definition. They’ve also come up with a set of criteria to accompany the definition that considers social equality, safety and transparency, among other things.

25 years ago, John Warner and Paul Anastas published their 12 principles of green chemistry. These principles were widely adopted as the field’s guiding framework and have helped green chemistry evolve into a major chemistry subdiscipline. By contrast, the field of sustainable chemistry has no such framework and is under-developed in comparison, despite having a great deal of overlap.

Moreover, recent legislative efforts by both the European Commission and the US Government require criteria that can be used to determine whether a chemical process is sustainable. The US Sustainable Chemistry Research and Development Act, 2021, for example, mandates the US Office of Science and Technology Policy to define sustainable chemistry.

Joel Tickner from the University of Massachusetts Lowell in the US, who put the working group behind the definition together, says groups other than chemical researchers will benefit from the definition. A key example is investors, who are increasingly conscious of the impacts of climate change and need some way to determine which companies are working in a sustainable way. Similarly, governments who want to incentivise more sustainable practices through tax benefits need criteria to determine who qualifies. ‘It’s important to find a measurable way to evaluate progress and to avoid greenwashing,’ explains Tickner.

The working group comprised 20 individuals from academia, industry, government, the investment community and the not-for-profit sector. While the majority were from North America or Europe, the working group accounted for bias arising from this by forming a subcommittee with a specific mandate to consider and incorporate other perspectives. This subcommittee was particularly focused on environmental justice, such as people from certain ethnic groups or economic demographics being disproportionately exposed to harmful substances released into the environment by the chemical industry because of where they live.

To arrive at a satisfactory definition, the working group had to make compromises. For example, Tickner says in an early draft ‘we had the word “eliminate” a lot, and a lot of the industry people said “eliminating hazards is just not going to happen, you can’t fully get rid of hazards.’ So, we changed some of the language to soften it, but then made it clear that this is where we’d like to go. We understand that we’re probably never going to get there, but unless you have that north star, you’re never going to aim for it.’

‘The definition has resulted from a considered and detailed process – it strikes me as as reasonable a working definition as any to go with right now,’ comments Helen Sneddon, an expert in green chemistry from the University of York in the UK. However, she says it’s important that the definition enables action: ‘There is value in having [a definition] to align different groups – and save time. Ultimately, we want to be making a difference not revisiting definitions to make sure everyone is on the same page each time different stakeholders meet.’

Tickner echoes this sentiment and accepts that the new definition is only a starting point. The next step will be to develop metrics that can be used to measure companies and processes by criteria laid out alongside the definition, thereby allowing it to be put to practical use.

References

This article is open access

A Cannon et al, RSC Sustain., 2023, 1, 2092 (DOI: 10.1039/d3su00217a)

No comments yet