Neurotoxin allows poisonous predator to subdue a mouse within half a minute

Scientists have characterised a peptide within the Chinese red-headed centipede’s venom that is key to its lethal bite. The toxin interferes with ion channels within nerve cells, allowing the centipede to take out creatures many times its body weight in a matter of seconds. The findings may point to a treatment for people bitten by centipedes.

’The capture efficiency of this species may be the highest among all reported venomous animals,’ says Ren Lai of the Kunming Institute of Zoology in China.

The centipede (Scolopendra subspinipes mutilans) hunts by grabbing prey and biting it using venomous claws. It weighs just 3g but can rapidly immobilise a 45g mouse.

The venom is a cocktail of toxins that simultaneously disrupts the victim’s cardiovascular, respiratory, muscular and nervous systems. Lai and colleagues identified one peptide in particular – named Spooky Toxin (SsTx) – that is responsible for the particularly rapid, deadly effect of this venom as it interferes with a family of potassium channels in the nervous system. Lai says the peptide shows no resemblance to any known animal toxins in protein databases.

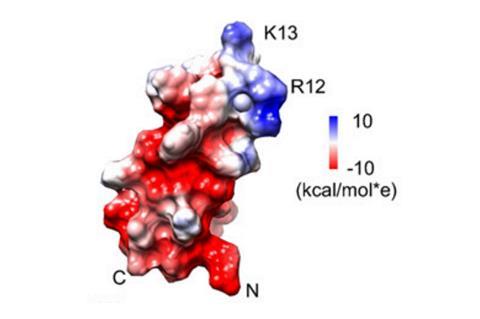

SsTx is compact, at 53 amino acids in length, with amino acids arginine and lysine at positions 12 and 13 forming a positively charged surface. These dock onto negatively charged outer parts of protein channels that normally allow potassium ions to flow out of nerve cells. This causes the nerves to fire relentlessly, throwing the heart and breathing apparatus into disarray. Just ten micromolar of the toxin impedes potassium channels within one-tenth of a second.

‘Most centipede prey are probably invertebrates, such as insects, and only the larger species are expected to tackle vertebrate prey such as small mammals,’ comments Ronald Jenner, a venoms expert at the Natural History Museum in London. He adds this is ‘the first study that shows that it is likely that a potassium ion channel-blocking neurotoxin in centipede venom may be the major weapon used to overwhelm large vertebrate prey’.

Centipede bites in human are not uncommon and can cause acute hypertension, myocardial ischemia and, in rare cases, death. Lai suggests an epilepsy drug could counteract centipede venom. ‘Retigabine is a KCNQ [potassium channel] opener and is used as an adjunctive treatment for partial epilepsies,’ he says. ‘It could be effective in neutralizing the venom’s toxicity.’

But Ian Mellor, a neuroscientist at the University of Nottingham, UK, points out that other toxins within centipede venom should also be taken into consideration. ‘There are many neurotoxic components that likely combine to cause rapid death,’ he says. ‘There are toxins targeting voltage-gated sodium and calcium channels as well as potassium channels.’

References

L Luo et al, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA, 2018, DOI: 10.1073/pnas.1714760115

No comments yet