Demand for fuels has constricted European supplies, pushing up prices and threatening rationing

The European chemicals industry is facing huge uncertainty as it contemplates a winter of reduced gas supply, amid soaring energy costs and rising raw material prices - in part related to Russia’s continued war against Ukraine.

While there was relief that Russia reopened the Nordstream gas pipeline after ten days of maintenance, flows are still a fraction of normal levels – Russia had already cut supplies to Germany by 60% in June, for example. The EU has asked member states to cut gas consumption by 15% from August, in anticipation of a total shutdown ahead of winter.

The German government has asked its citizens and industry to cut back on energy consumption so the country can try to boost its reserves before winter, but rationing looms. An economic research institute, IFO, found increasing uncertainties mean chemical companies expect to scale back production in the coming months.

If supplies are shut down and there’s a cold winter, ‘you could well get prolonged periods where large, integrated petrochemical facilities are just not operating … that just ripples through global supply chains,’ says Alan Gelder, vice president of refining, chemicals and oil markets at Wood Mackenzie. Where impacts will be felt is ‘massively uncertain’ he adds – depending on the products, whether they’re imported or exported, and whether ‘industries all go down together’.

If supplies are shut down and there’s a cold winter, then you could get petrochemical facilities just not operating

In the UK, the Chemical Industries Association (CIA) is looking at where there’s reliance on raw materials from Germany, and the potential impacts on UK operations and supply chains. It’s not just chemicals that will be impacted but engineering components from Germany that keep processes moving.

German companies are developing contingency plans to tackle shortages. BASF says it can continue to operate facilities with reduced supplies but would have to shut production at its Ludwigshafen site – the world’s largest chemical complex – were gas supplies to drop below 50% for an extended period. Evonik is spending several million euros to extend the life of a coal-powered plant at its largest production facility in northern Germany, that will also supply power to other companies at the chemical park. It told Chemistry World that ‘We assume that further cuts in the supply of natural gas might lead to challenges in the supply chain and potential production restrictions, but that our major integrated production can be maintained.’

While it’s clear governments will prioritise households over industry, there are critical chemical products used in food production, pharmaceuticals and water treatment that industry wants to see protected.

The German chemicals sector overwhelmingly relies on gas, having almost entirely made the transition from coal and oil. In an average year the sector consumes around 135TWh of gas – around 15% of the country’s total natural gas consumption. Around a quarter of that gas is used as a raw material, while the rest is used to generate energy for plants and processes.

In January 2021 prices were around €20/MWh. That has risen to €150–160/MWh, with further rises expected as supplies move to expensive liquefied natural gas (LNG) from other parts of the world. Even that arrival is hindered by the fact that Germany doesn’t have its own LNG import terminals. The first of four floating terminals is due to come on stream at the end of the year, ‘but that won’t totally solve the problems this winter,’ says Jorg Rothermel, head of energy, climate protection and raw materials at Germany’s chemical industry association, VCI. Nor will imported LNG cover the entire gap left by Russian supplies.

Rothermel says chemicals production is down 3% because energy prices and raw material costs are impacting demand. ‘That’s not hugely significant, but it does mean there’s no growth.’ Ammonia production (which uses gas as a raw materials) has been especially hard hit by rising gas prices – even before Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, European manufacturers BASF, Yara, Borealis and Fertiberia had all announced cutbacks in production.

A BASF spokesperson said the company paid an extra €1.5 billion for gas in 2021 compared to 2020, and €900 million more for gas in the first quarter of this year compared to the same period in 2021. However ‘solid demand’ for its products means it will be increasing prices further to compensate for those costs.

German commodity chemicals producers that face less international competition had been able to pass through increased costs. That’s harder for speciality and fine chemical producers that face much stiffer international competition, says Rothermel, but he expects that eventually commodities will face the same pressures.

Germany’s Lanxess, which produces additives and engineering materials, raised prices by 30% in the first quarter, while last month it announced a 10% price increase in ion exchange resins and iron oxide adsorbers for water treatment applications. It also introduced a monthly variable surcharge to ‘compensate the extraordinary cost increases in raw materials, energy and transportation’. Suppliers of high-performance polymers such as France’s Arkema and Belgium’s Solvay have also passed on rising costs to their customers.

Gasoline prices are very strong and naphtha is very weak, so if you’ve got anything that’s high octane that you can blend with naphtha to make gasoline, it [gets sucked] into the gasoline pool

While the UK is not as reliant on Russian gas, it’s still heavily interconnected through the European gas network, says Nishma Patel, policy director at the CIA. Coming on top of Covid and the impact of Brexit, increased raw materials and energy costs mean ‘for the first time we’re seeing [chief executives] suggesting there is going to be at least a temporary fall in sales.’ Up till now companies have been able to either absorb or pass on cost increases but that may have reached its limits, she adds.

Chemicals for key sectors such as rubber, plastics and pharmaceuticals have also been hit by surging demand for gasoline in both Europe and the US, exacerbated by limited refining capacity as a result of some rationalising during the pandemic. China also reduced exports of refined products says Gelder, ‘so you had this really odd thing of gasoline [prices] being very strong and naphtha being very weak, so if you’ve got anything that’s high octane that you can blend with naphtha to make gasoline, it just becomes a real blending economic gain. That also sucked in a lot of traditional blending components into the gasoline pool.’

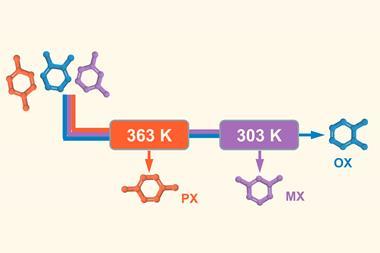

That blending demand has created competition for high octane feedstocks such as toluene, ethyl benzene and mixed xylenes. According to commodities data firm, ICIS, prices of Benzene, used worldwide in industrial processing, are more than double what they were last July. Toluene and xylene, used in plastics and textiles are also sitting at historic highs, with toluene around €1750 per tonne in northwest Europe (from €810 a year ago) although prices may now be on their way down. Unprecedented prices of mixed xylenes are impacting manufacturers of para-terephthalic acid (PTA) and poly(ethylene terephthalate) (PET). Nigel Davis, insight editor at ICIS, says contract negotiations for June pricing of European paraxylene were still ongoing in early July, with producers asking for higher prices to reflect the demand they’re seeing from gasoline makers. Paraxylene cost €820 a tonne this time last year, whereas May contracts were for €1240.

However, there are signs prices are coming down owing to a slowdown in downstream sectors, such as plastics (notably polypropylene) for the automotive industry, says Farrukh Novruzov who covers the European chemicals sector at Wood Mackenzie. International companies that would have been making cars in Russia no longer are, and that has combined with continued stresses in the semiconductor supply chain.

Some member states are taking advantage of permission to relax EU biofuel blending mandates, in a bid to lower fuel prices for consumers. However, Davis points out that France – Europe’s largest bioethanol producer – has seen burgeoning sales of its E85 blend which contains 15% bioethanol. Prices for that blend are ‘significantly lower than gasoline blends with a lower bioethanol content, so France has managed to partly offset rising gasoline prices.’

There are no quick fixes for Germany’s industry to replace Russian gas in the short term, with further process efficiencies offering only limited potential. It will take longer to switch to renewable energy and technologies like electric crackers. But VCI’s Rothermel is clear that the crisis will only speed up the industry’s transition away from fossils fuels. ‘We are already on a transition pathway.’

No comments yet