As more nations fund science and global R&D investments shift east, traditional science leaders like the US and UK are under pressure

The US remains the single largest funder of research and development (R&D) in the world, but emerging trends show the global science funding landscape is becoming more diverse, according to new analysis by the American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS).

In terms of overall R&D spending, the data show that among the 34 members of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), total R&D spending rose 2.1% in real terms from 2013 to reach $1.1 trillion (£750 billion) in 2014.

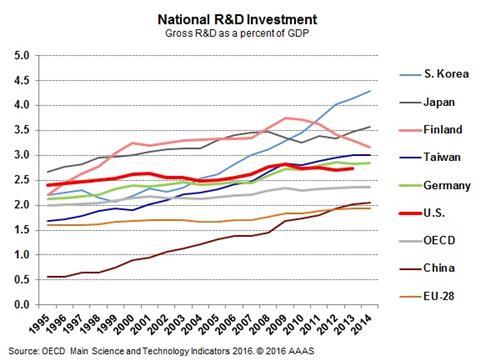

As a percentage of global GDP, OECD R&D rose from 2% in 1995 to 2.1% in 2004, and then grew more rapidly to reach 2.4% in 2014. However, R&D funded by governments in the advanced OECD economies has declined or flattened since the global financial crisis. The Obama administration fell just short of the president’s goal to increase US spending on R&D to more than 3% of GDP.

At the same time, the new AAAS analysis by senior project coordinator David Parkes concludes that global R&D investment is shifting to east Asian nations. He notes that South Korea doubled its R&D spending as a share of GDP over the past 20 years to reach 4.29% in 2014.

‘Massive leaps’ in China

Similarly, China has taken ‘massive leaps’ in research spending, according to Parkes, more than tripling R&D intensity from 0.64% in 1997 to 2.05% in 2014. He points out that China’s latest five-year plan would increase the nation’s R&D investment to 2.5% of GDP by 2020. In its most recent report, the OECD predicted that China would overtake the US in total R&D spending by about 2019.

The global volume of scientific production, as measured by the number of scientific publications, increased by 7.9% annually from 2003 to 2012, the AAAS data show. Over this period, the total number of these publications rose by 51% in the US, and by comparison China’s output quadrupled.

Parkes says China is the world’s second largest creator of scientific publications, and is catching up with the US fast. However, the quality of the research coming out of China appears lower. Taking into account the OECD’s ‘excellence’ indicator – defined as research publications that rank within the global top 10% most-cited – there is a considerable gap between western nations and China.

Nevertheless, Parkes notes that China is on track to overtake Japan’s excellence rate, while the US, UK and Germany have all seen their proportion of publications among the top 10% stagnate or decline in recent years.

Caroline Wagner, a science and technology expert who serves as chair of international affairs at the Ohio State University’s school of public affairs, says China is now the US’s biggest single cooperative partner in science. ‘This is a very big change for the US, because our focus has tended to be European, and our biggest relationship has been with the UK for many years,’ she tells Chemistry World.

‘Earthshattering change’

However, last year China surpassed the UK to become the US’s biggest scientific partner. ‘That is an earthshattering change in our global relationships,’ Wagner states.

Prior to 1990, she says only six countries paid for almost all of the R&D underway globally. Wagner applauds the fact that the so-called ‘mezzanine countries’ like Mexico, Brazil, and the BRICs (Brazil, Russia, India and China), are all carrying out more science.

‘To the extent that we look at science as a social good, that is fantastic,’ Wagner states. ‘Many more countries have capacity now to solve problems that require science and technology … overall that has just got be looked at as a good thing,’ she says.

Wagner also emphasises that global R&D is not a zero sum competition. ‘It is not like if they invest more they are going to get ahead, because all of these countries are very intertwined in terms of science and technology – there is a huge amount of interdependence,’ she remarks.

The traditional global science leaders like the US and the UK need to survey the R&D taking place across the globe and select the most important developments to make them locally useful, Wagner advises. ‘What we need to do is scan globally and reinvent locally,’ she concludes.

Kieron Flanagan, senior lecturer in science and technology policy at the University of Manchester, agrees. By themselves, he says, these AAAS figures don’t tell us very much about science. ‘R&D isn’t science, and the R&D intensity that they are looking at at the national level is not driven by what governments do in terms of funding science, it is driven by private business investment, which is affected by lots of different things,’ he states.

As more and more nations move into global science and technology, the overall share held by nations that are traditionally strong in these areas is bound to decline, according to Flanagan. ‘The US share of a rapidly growing cake is inevitably going to get smaller,’ he tells Chemistry World. ‘It doesn’t mean that there is anything to be concerned about, as long as you are maintaining your own strengths so that you can tap into all that extra global science and technology and benefit from it.’

No comments yet