Although its short term future is secure, UK’s role in future projects is on shakier ground after Brexit vote

The UK’s future in pan-European scientific projects may be in doubt following the country’s vote to leave the EU. Scientists are now seeking assurances that the vote will not affect the UK’s position over the long term.

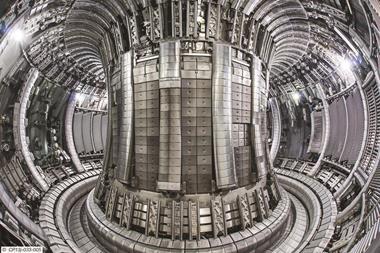

‘We are very vulnerable at this point, mostly we’re vulnerable from the uncertainty,’ says Steven Cowley, head of the Culham Centre for Fusion Energy (CCFE) in the UK. The CCFE is at the centre of fusion research and is working with 40 teams across Europe to run the world’s only operational fusion device, the Joint European Torus (Jet).

The European Consortium for the Development of Fusion Energy (EUROfusion) fund Jet’s experiments. Set up in 2014, EUROfusion is jointly run by 26 EU member states along with Switzerland, and is funded through the European Atomic Energy Community, Euratom.

Although it does not fall under EU control, Euratom nonetheless funds nuclear research through Horizon 2020 funding. EUROfusion will receive €420 million (£359 million) from this fund between 2014 and 2018 – a large portion of which will support Jet’s successor, Iter, set to come online in 2025. Following a joint agreement with the European commission, the CCFE will operate Jet until 2018.

[[Until 2018, nothing happens]]But it is vital Jet operates past 2018, according to Cowley. ‘We expect Jet to go on almost until Iter because it’s the only machine in the world that can actually do fusion and can run with tritium,’ he says. ‘It plays a unique role in the world programme.’ Cowley admits, however, that the CCFE is in limbo until negotiations start and is adamant that the UK’s position is established before the government activates Article 50, the protocol for exiting the EU.

Tony Donné, EUROfusion’s programme manager, is quick to assuage any immediate concerns, but can make no guarantees for the future. ‘Until 2018, nothing happens,’ comments Donné. ‘Of course what happens afterwards is more uncertain because if the UK goes out we are confronted with the fact that we have a very large European facility on UK soil.’

As for the UK’s involvement in Iter, it looks as though the collaboration is safe. ‘As the United Kingdom will remain part of the EU until negotiations are concluded and ratified – a process that could take many years – its relation with Iter, for the present, will not be affected,’ Iter said in a statement.

Other European projects that do not rely on EU funding or governance, such as Cern’s Large Hadron Collider, will be unaffected by Brexit. ‘Cern’s success over the years is built on international collaboration, but we are not part of the European Union,’ said Cern in a statement. ‘Britain’s membership of Cern is not affected by the UK electorate’s vote to leave the European Union.’

Ultimately, the UK’s role in large-scale EU projects may come down to politics, according to Donné, who wants the UK involved in all future projects. ‘We are very keen in continuing this collaboration and to find ways forward to continue. But, of course, we depend very much on the politics here,’ warns Donné. ‘[The UK] government needs to make a decision on what it really wants.’

No comments yet