The organic compounds isocyanides and isonitriles are infamous for their awful smell. ‘It is a combination of hot metal and vomit,’ says odour chemistry expert Luca Turin at the Alexander Fleming research centre in Athens. ‘God forbid, if you dropped 10ml of isonitrile on the floor, you’d run for your life.’ But now Russian researchers have found a way to tame the repulsive smell of isocyanides.

Isocyanides, also known as isonitriles and carbylamines – a functional group of a triple-bonded carbon and nitrogen atom, which bonds to other chemicals through the nitrogen – are important in synthesis as building blocks for other organic compounds.

But their overpowering stink severely limits their use. Many labs have banned them – Derek Lowe who blogs at In The Pipeline and has a section on chemicals he won’t work with has compared their odour to ‘Godzilla’s gym socks’ and they’ve been investigated as non-lethal weapons. ‘The intensity of the odour is so preposterous that no fume cupboard can deal with it,’ Turin says.

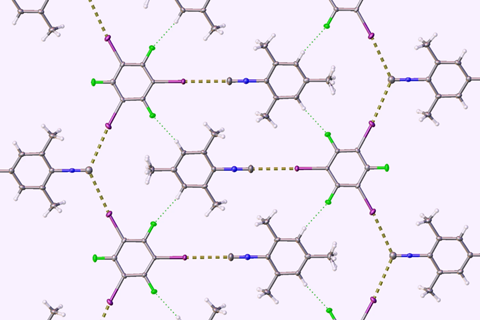

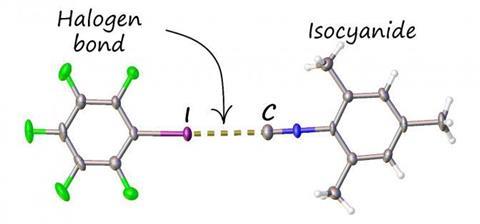

Now scientists have devised a way to almost eliminate the smell of isocyanides while keeping their valuable chemical properties, by establishing a halogen bond – an intermolecular interaction, similar to a hydrogen bond – between isocyanides and a benzene compound containing iodine.

Research chemist Alexander Mikherdov and his colleagues at St Petersburg University in Russia use transition metal complexes of isocyanides in crystal engineering. After noting that isocyanide–metal complexes don’t have the same overpowering smell, they set out to replace the metals with a halogen bond donor, which they hoped could cut the odour of isocyanides in the same way.

By crystallising or grinding isocyanides with iodoperfluorobenzenes, they succeeded in creating a series of isocyanide adducts with only a very faint smell – around a 50-fold reduction – and most of the original chemical properties, Mikherdov says.

The adducts can be used as benchtop reagents, without precautions like fume hoods, and can be safely stored at room temperature. Their main drawback is that more must be used than pure isocyanides, and that iodoperfluorobenzenes irritate the skin – so researchers should avoid contact with the adducts. ‘However, I would also strongly avoid skin contact with normal isocyanides, because it is really difficult to wash out the smell,’ Mikherdov says.

Turin, who was not involved in the research, says the molecules created by the halogen bond are too large to be smelled – human smell cuts out above 15 carbon atoms per molecule, and the isocyanide adducts have at least 16.

‘[Isocyanides] are hugely useful as building blocks for pharmaceuticals, because frequently you want a carbon mixed with nitrogen,’ he says. ‘I imagine that this would be an extremely useful ploy to lower their environmental impact.’

References

A Mikherdov et al, Nat. Commun., 2020, DOI: 10.1038/s41467-020-16748-x

No comments yet