Discolouration of iconic Washington, DC, building’s red stone is all down to a manganese oxide-rich rock varnish

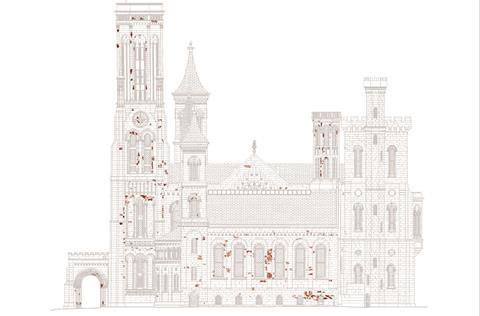

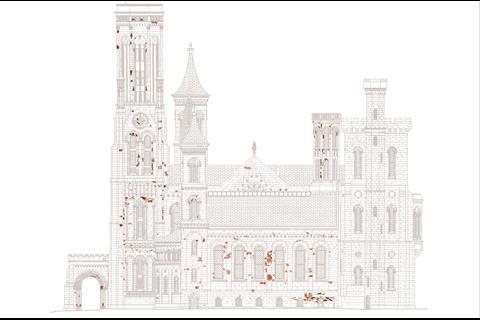

For the past decade, mysterious black patches have been appearing on the Smithsonian Institution’s red brick ‘castle’ in Washington, DC.

Now, chemists analysing the discolouration have identified the culprit as a manganese-rich rock varnish – a thin outer coating that forms when chemicals oxidise on the surface of the stone.

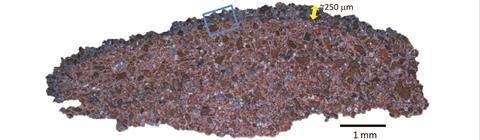

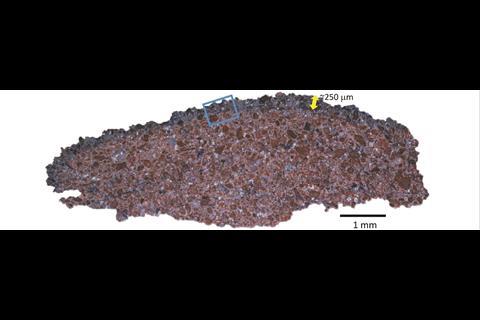

Rock varnishes are well known to geologists, but are usually found on dry, undisturbed desert rocks, having formed over hundreds or even thousands of years. ‘This study represents the first significant examination of rock varnish on architectural stone,’ write Edward Vicenzi and colleagues at the Smithsonian’s museum conservation institute, who investigated samples of the discoloured parts of the building using various techniques including scanning electron microscopy and x-ray fluorescence spectroscopy.

The irregular patches of discolouration on the Smithsonian’s red sandstone bricks puzzled scientists when they began to appear in the mid-2000s, and the suggestion that they could be a rock varnish only surfaced in the last few years. Vicenzi and colleagues’ investigation showed the appearance and composition of the varnish is similar to that which forms on desert rocks. It is rich in manganese and zinc compounds, with smaller amounts of calcium, zinc, copper and nickel.

But its formation is still somewhat mysterious. Varnishes that form in arid environments are most often the result of airborne particles accumulating on dry, undisturbed rock surfaces, and reacting over time to form a coating. But conditions where the Smithsonian is located are classified as humid subtropical – the sandstone gets 10 times more rainfall than desert rocks would, and this tends to disrupt the accumulation of these particles. Instead, the researchers suggest, bacteria or other microorganisms may be responsible.

‘The patchy distribution of varnish is less consistent with a chemical process, which would lead to the development of a more uniform coating, and more suggestive of biological colonisation,’ they point out. The manganese-containing particles are still likely to have come from the surrounding environment, brought by wind or rain, however, as the sandstone itself is not manganese-rich.

The team notes that it might offer a rare opportunity to study the early formation of a rock varnish – most of those found in the natural world are thicker and better established, with well-defined layers and complex communities of microbes.

George Rossman, a mineralogist at the California Institute of Technology, US, agrees that this could be a potential angle for future research. ‘To my knowledge there has been little discussion of manganese deposits on buildings, so this is an interesting contribution,’ he says.

He also thinks it would be possible to remove the blackened areas without damaging the brickwork. ‘There are potentially easy ways to quickly remove the manganese involving reduction,’ he says. ‘We routinely clean the black manganese deposits off rocks and fossils.’

References

E P Vicenzi et al, Heritage Sci., 2016, DOI: 10.1186/s40494-016-0093-2

No comments yet