Russia’s war against Ukraine will impact supplies of metals, noble gases and more

As Russia’s offensive on Ukraine continues, manufacturing activities and exports from Ukraine are severely impaired or have ceased. Russia itself is subject to a growing list of economic sanctions from dozens of countries, and companies with operational links to Russia are evaluating their options.

London-listed shares of Russian state-owned gas supplier Gazprom tumbled 50% on 28 February, and Shell said it would exit its joint venture with the company. BP committed to selling or writing off its 20% stake in Russian state oil company Rosneft, held since 2013. ‘We are at war and we need to consider those companies as an extension of the Russian state,’ energy expert Thierry Bros at Sciences Po Paris told the Wall Street Journal.

Meanwhile, the European Commission intends to accelerate plans to wean the EU off its dependency on Russian energy. An imminent new EU strategy is expected to call for a 40% reduction in fossil fuel use by 2030 and further increases in investment for renewables. Energy makes up half of Russian’s exports and a fifth of its GDP.

Western companies working in Russia are coming under pressure from sanctions and public opinion. German oil and gas producer Wintershall Dea, majority owned by BASF, is involved in three onshore natural gas projects in Russia and the Nord Stream 2 pipeline to bring gas into Europe. The company has condemned the invasion, and will not advance or implement any additional gas and oil production projects in Russia. Wintershall will also write off its financing of Nord Stream 2, totalling around €1 billion (£830,000). The $11 billion (£8 billion) Nordstream 2 pipeline, owned by Gazprom, has been mothballed, while the company in Switzerland overseeing it has filed for bankruptcy.

With the price of oil hovering around $107 a barrel on 1 March, member countries of the International Energy Agency (IEA) agreed to release 60 million barrels from emergency stockpiles in response to Russia’s invasion. This equates to 2 million barrels a day for 30 days. Russia exports about 5 million barrels a day of crude, roughly 12% of global trade.

Noble gas supply dissipating

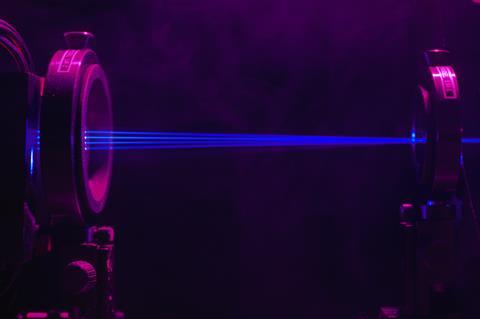

Ukraine is the largest supplier of noble gases used in chip making, especially neon, of which 90% is used in lasers for etching. Neon, krypton and xenon are all byproducts of the air separation plants that supply large steel mills with oxygen. All three are critical to semiconductor manufacturing, especially high-end chips. Global neon production is around 600 to 700 million litres, with 200 million in the US and 100 million in Europe, says independent consultant Dick Betzendahl. But supply was already constrained, because China shut steel mills to reduce pollution for the Winter Olympics and to suppress demand for iron ore from Australia, he explains. Neon prices tripled in the six months before the war.

The two major purifiers for Russian and Ukrainian neon are in Odessa, Ukraine, and getting the product there is probably near impossible

As byproducts of steel production, building capacity for xenon, krypton and neon is very difficult. Supplies also fell because steel demand was lower during the pandemic. Price volatility of these gases means private investors will not risk putting capital into their production. ‘Only China added significant capacity in the last 10 years,’ says Betzendahl, ‘because they want to be self-suficient in these critical rare gases.’

The electronics industry will struggle to get adequate supplies. ‘Due to the war, Russia and Ukraine are probably producing around 100 million litres of neon, whereas they were producing 200 million prior to the conflict,’ says Betzendahl. ‘A real problem is that the two major purifiers for Russian and Ukrainian product are in Odessa, Ukraine, and getting the product there is probably near impossible.’

Betzendahl says krypton alone has gone from costing a few cents per litre to $4–5. ‘Everything points to (possibly severe) shortages for krypton, neon and xenon,’ he says. ‘If you run a multi-billion dollar [fabrication plant], you are going to pay any price [for these gases]. They’re going to bid up the prices to get supply.’

Metals under strain

Russia is a major exporter of platinum and palladium, important metals in catalysts for vehicle exhausts and elsewhere. The risk of disruption to supply is immense, analyst Natasha Kaneva at JP Morgan told the Financial Times, with Russia accounting for 12% of global platinum and 40% of palladium. High gas prices and tight supply could impact smelters elsewhere, compounding the problem.

Russia produces around 14% of global aluminium, with Rusal being the world’s top producer outside of China, accounting for 6% of global supplies. Aluminum had sunk to around $1500 a tonne in April 2020, but has been rising steeply since. After the Russian invasion, it reached record highs above $3400 a tonne.

In its 2020 report on critical raw materials, the European commission noted that Russia produces 22% of the world’s titanium, 20% of the EU’s supply of phosphate rock, 26% of the world’s scandium and 19% of global vanadium. While less critical, Russia also supplies 10% of global nickel, 4% of cobalt and over 3% of copper.

According to a US Geological Survey report from 2018, Ukraine was ‘likely to remain one of the world’s leading producers of manganese ore, titanium ore and titanium sponge.’ The equivalent report for Russia noted that the country is a global leader in many metals and industrial minerals.

The war has already impacted some industry supply lines. Car maker Volkswagen responded to the invasion by shutting two factories in Germany for a few days.Specialist suppliers from Ukraine, including Leoni and Nexans, provide automakers across Europe with electric wiring for cars. The world’s three largest shipping companies – Maersk, MSC Mediterranean and CMA CGM – are to temporarily stop delivering cargo to and from Russia.

Meanwhile, biotech leaders published an open letter pledging to cease investing in Russia, reject investment from Russian funds, stop collaborations and service agreements with Russian companies and halt trade in goods with Russian companies (except for food and medicines). The pressure to isolate Russia is likely to escalate so long as the war continues.

No comments yet