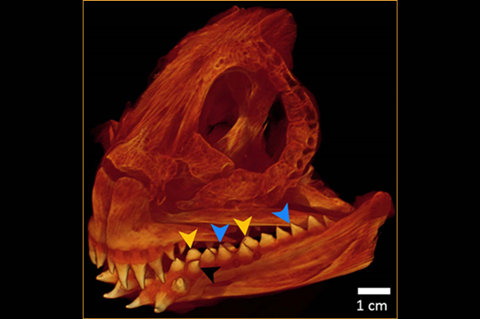

The teeth of the Atlantic wolffish, a bottom-dwelling predator in the North Atlantic Ocean, are strong enough to crush hard-shelled prey and now new analysis has revealed that their core contains an extremely rare material that helps them carry out that task.

An international team led by researchers at Hebrew University in Jerusalem, Israel, has found that the osteodentin in the teeth of Atlantic wolffish is auxetic, shrinking in every direction when squeezed along its length.

This discovery helps explain how the wolffish’s teeth can withstand repeated, punishing forces. It could also help inform new designs for tougher, more resilient synthetic materials.

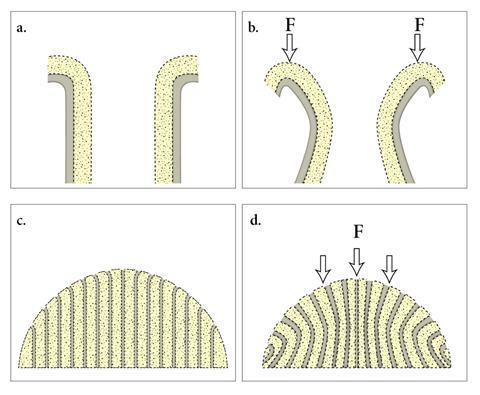

Unlike most materials, which expand sideways when compressed along their length, when the researchers applied force along the tooth’s axis that mirrored the wolffish’s natural biting forces the osteodentin consistently contracted laterally, as well as longitudinally. This behaviour corresponds to materials with a negative Poisson’s ratio, which describes materials that become fatter when stretched or narrower when compressed, unlike conventional materials.

For all eight teeth examined, the researchers mostly recorded Poisson’s ratio values for the osteodentin between -1 and -2, a range rarely seen in engineered materials. For example, most steels are about 0.3, and rubber is approximately 0.5.

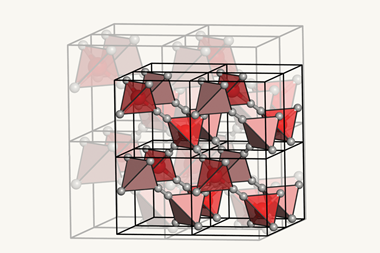

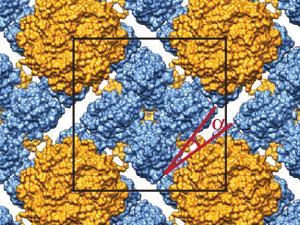

The unusual auxetic properties of the osteodentin is thought to be related to the microstructure of the teeth. Canals 10–20μm in diameter run from the base of a wolffish tooth to its tip, curving outward as they near the top. When the tooth is compressed these canals collapse inwards, shrinking the osteodentin laterally and providing extra strength to the tooth.

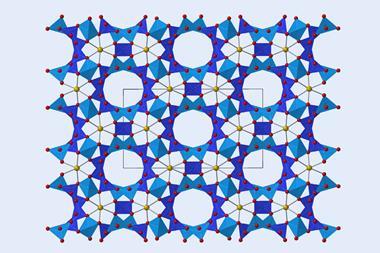

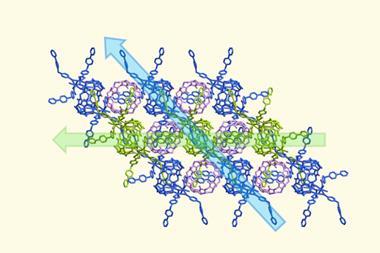

There are a few natural examples of auxeticity, including the achilles tendon, cat skin and zeolites. And, more than a decade ago, researchers in France developed a material whose volume increased whether it was stretched or squeezed. Its structure comprised a single wire twisted into a helix that was entangled into a disordered ball and then compressed into a cylinder. US researchers also designed a protein crystal sheet that thickened when stretched and shrunk when compressed in 2016.

References

R Shahar et al, Acta Biomater., 2025, DOI: 10.1016/j.actbio.2025.11.047

1 Reader's comment