The catalysis innovator on the thrills of heading to the mountains and having a reaction named after him

John Hartwig is the Henry Rapoport professor of chemistry at the University of California, Berkeley, and received the 2019 Wolf Prize in Chemistry. His research aims to discover and develop new reactions that are catalysed by transition metals, and he was one of the developers of the Buchwald-Hartwig amination, one of the most used reactions in drug discovery. He was speaking to Katrina Krämer at the 2019 American Chemical Society national meeting in Orlando, Florida.

John Hartwig is the Henry Rapoport professor of chemistry at the University of California, Berkeley. He received the 2019 Wolf Prize in Chemistry. His research aims to find new metal-catalysed reactions, and he was one of the developers of the Buchwald-Hartwig amination, one of the most-used reactions in drug discovery. He was speaking to Katrina Krämer at the 2019 American Chemical Society national meeting in Orlando, Florida.

I love to be outside. My family and I go backpacking and hiking frequently, and I go cycling often. If you live in Berkeley, you’re just minutes away from a very large park in the hills. There are miles and miles of hiking and redwood trees and open space. We go skiing when the snow is good. Since we moved to California, we’ve been going to the Sierra Nevada mountains for backpacking trips.

Many decades ago, I went to India for about a month and went to the mountains with another group that I had met there. But they turned out to be too mellow. I then went out for a few nights with just a guide and porter and told them to make it tough. It was pretty brutal. It got to the point where I wasn’t sure I was going to make the next step before falling off.

The food in Berkeley is great; lots of farmers markets. I love to cook, particularly Italian food, so my family and I always eat a very good meal, even on weeknights. At the same time, San Francisco is nearby, and there’s lots we do in the city, like music and theatre and other cultural events. We’ve gone to many operas over the years. Verdi’s are the best of course.

Growing up, I didn’t think that much about my career. As a kid, I really wanted to play baseball or basketball – shortstop for the Yankees, or guard for the Knicks – but it became pretty clear early on that that wasn’t going to happen. I was always interested in math and science. I went to college thinking I would be an electrical engineer, or at least my father thought it was a good idea for me to study that. I took a range of different science courses, and I really loved the chemistry classes. So I ended up switching out of engineering and into chemistry.

I played on our high school football team in my freshman year. We were terrible. We didn’t win any games and typically lost by 40 points per game. I switched to playing soccer and turned out to be a very good goalie. But our team scored five goals in 16 games, and three of those goals were in one game. So if I let in just one goal, the best we’d do if we were lucky enough to score was tie. That was certainly a challenge, but it was enjoyable anyway.

I think that one of the biggest unanswered questions in science – at least in chemistry – is how to create molecules that are precise enough to be able to solve the many problems in human health that we haven’t solved. Personalised medicine is something a lot of people talk about – and it’s aspirational – but how do we get a different drug for each person if it costs several billion dollars to develop each drug? Is there some way to change the entire process of drug development?

There’s a lot of distrust of science. I think there are a lot of people who don’t understand the scientific thought process well – being able to recognise the difference between current theories and established information. Of course, there are aspects of a topic that we don’t know, but that doesn’t mean that the core is unknown. I think if people understood the process of establishing theories better, they’d be more supportive.

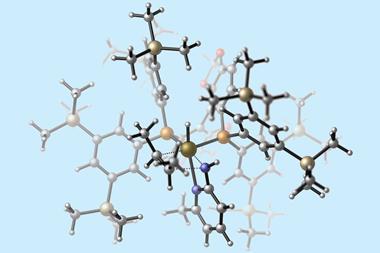

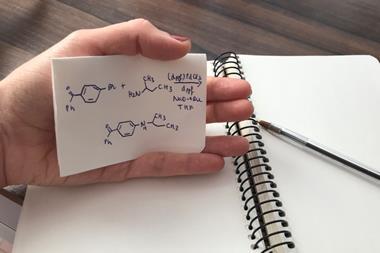

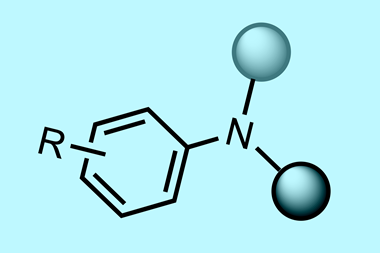

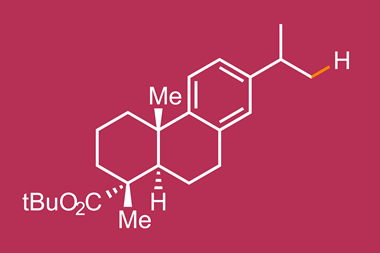

Having a reaction named after me is kind of strange, because there wasn’t some magical moment or a ceremony where it got named. The first experiments were done at a very early stage of my career, when I had a group of five or six people, half of them working on a different project. We were interested in reaction mechanisms and understanding how the cross coupling to make carbon–nitrogen bonds would work, without really recognising the synthetic importance of the reaction.

It was kind of a thrill to see that people were beginning to call the reaction ‘Buchwald–Hartwig amination’. It’s certainly satisfying that our name became associated with the reaction even though we were a small group and there were other, more established researchers like Stephen Buchwald working on the problem.

Someone pointed out that there was an entry in the Merck index that sort of made the name official. But by the time people started to call the reaction by that name, we were also very heavily involved in developing catalysts for C–H functionalisation and among other projects. So our biggest worry was more how well these new projects were going than who was naming what reaction.

No comments yet