Meera Senthilingam

This week, Brian Clegg explores the perils of association by name.

Brian Clegg

There’s an undoubted cachet in having a product or substance named after you. But it’s arguable that one compound no one wants to be remembered for is a chemical weapon – yet such was the burden of the US chemist, Winford Lee Lewis, who had the doubtful honour of having lewisite named after him. Technically 2-chloroethenylarsonous dichloride, lewisite is a relatively simple compound of carbon, hydrogen, arsenic and chlorine.

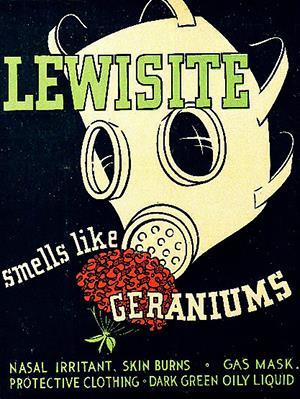

Like the older mustard gas, lewisite both causes blistering on contact (known as a vesicant) and a powerful irritation to the lungs, disrupting the function of an enzyme that plays a role in one of our metabolic pathways. Potentially released as an aerosol or into drinking water and onto food, the compound produces severe blisters on contact, breathing problems, nausea, vomiting and a cardiovascular reaction known as ‘Lewisite shock’ resulting in a severe drop in blood pressure. Thankfully, though, unlike mustard gas, lewisite has rarely been used on the battlefield. In principle this oily liquid boiling at around 190 °C is colourless and odourless, but production impurities often give it a tint that can range from brown to violet-black with a smell that is said to be similar to that of geraniums.

In effect the compound was produced by accident by a Belgian-born American PhD student and Catholic priest, Julius Nieuwland, who was working on reactions of acetylene. His work resulted in the production of the synthetic rubber neoprene, but a less savoury outcome was the reaction of acetylene with arsenic trichloride, which produced lewisite, leaving Nieuwland in hospital as a result of his brief exposure. Nieuwland’s thesis advisor John Griffin brought Nieuwland’s work and the noxious compound to the attention of Winford Lee Lewis, a researcher in chemical weapons, whose further work on it gave it its name before it was weaponized in early 1918 – too late, in practice to be used in the first world war. Lewis is said to have remarked that lewisite was ‘the stuff beside which mustard gas becomes a sissy’s scent.’

The use of chemical weapons in the first world war, first by the Germans and then by the Allies, produced very mixed responses. Many military personnel on both sides were privately disgusted by the horror of this silent, creeping killer. One German officer, reflecting on his army’s early use of gas commented ‘Poisoning the enemy just as one poisons rats struck me as it must any straight-forward soldier… repulsive.’ However others were less concerned. Shortly after the war finished Winston Churchill said ‘I do not understand this squeamishness about the use of gas.’ He saw it as a positive that it ‘spread a lively terror.’

Although Nieuwland himself is said to have not considered the development of lewisite as a chemical weapon he too defended the use of such products in an interview in 1936, commenting:

‘By the introduction of gas and other modern instruments of warfare, a progressively small percentage of combatants have been killed. In biblical times, thousands of men met in the middle of a plain and slashed one another until only a few were left standing. Today, the primary aim is not to kill but to incapacitate. And poison gas is an ideal method of achieving that aim. If a man goes to a hospital suffering from gas, he is as useless as if he were dead and to care for him, several other persons must be kept out of the battle lines. The chances are that ultimately the victim will recover.’

The Americans continued to experiment with lewisite on and off, giving it the delightful nickname the ‘dew of death’, with a renewed interest during the second world war, but again it was not deployed and was declared obsolete soon after. It was also known to be manufactured by the Japanese, the Soviet Union and the Germans, who were able to access its formula as a result of a 1921 publication in the Journal of the Chemical Society, and saw a rare deployment by the Japanese in China during the second world war. Other countries suspected of production of lewisite included Iraq, which may have used it against Iranian targets, and North Korea.

One positive outcome from the fear of the use of lewisite during world war two was the development at Oxford University of dimercaprol, also known as British anti-Lewisite. This sulfur-bearing organic compound was, as the name suggests, developed as an antidote in case lewisite was deployed, but it has since proved a useful treatment for heavy metal poisoning, particularly arsenic, as the dimercaprol binds onto heavy metals, preventing them from acting on some of the key sites where they can cause damage. It’s not an ideal antidote, as it is itself poisonous with serious side effects, but is still advantageous if used carefully.

It is hard indeed to find anything positive to say about a weapon of mass destruction. Perhaps all we can be grateful for is the spin-off development of dimercaprol and the thankful knowledge that lewisite has rarely been put to its horrendous intended use.

Meera Senthilingam

Science writer Brian Clegg, with the chemistry of lewisite. Next week, a pleasant surprise emerges from sewage.

Ben Valsler

Many species fight among the faeces vying for dominance and continually evolving new ways to stay on top. As a result, the chemical mechanisms developed by some of these species make ideal drug candidates.

Meera Senthilingam

Discover the beneficial compounds emerging from this in next week’s Chemistry in its Element. Until then, thank you for listening, I’m Meera Senthilingam.

No comments yet