Meera Senthilingam

This week, we head to the UK countryside for some healing. Taking us there is Brian Clegg

Brian Clegg

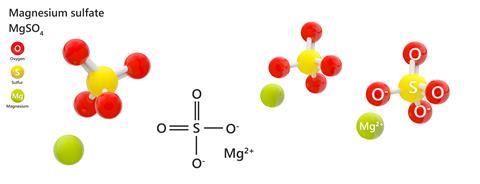

The town of Epsom, in the English county Surrey, is probably best known for its racecourse, but it is also a town with mineral springs and gave its name to a particular substance extracted from them, known as Epsom salts. This is a hydrated form of magnesium sulfate, where the basic MgSO4 gains seven water molecules to form epsomite or magnesium sulfate heptahydrate.

According to tradition, Epsom’s healing waters were first discovered in the early seventeenth century by a local villager, Henry Wicker, who found a natural spring on Epsom Common to water his cattle on a particularly dry summer. His cattle wouldn’t drink the water, but Wicker decided the strong mineral taste of the spring would give Epsom a spa.

The salts were named in 1695 by one Nehemiah Grew, who was granted a Royal patent for the making of his ‘bitter purging salts’. But he may not have been the first to produce them, as a local chemist, Francis Moult, claimed to have been manufacturing the salts for years. What was initially seen as something to produce a purgative drink was soon found to have more pleasant uses.

The best-known laboratory function of magnesium sulfate has a strange echo of those purgative origins. This is pure magnesium sulfate, without any attached water molecules and hence anhydrous. This form of the compound will rapidly grab any nearby water molecules. In damp air, the white powder rapidly deliquesces. But what may seem a disadvantage proved very useful to organic chemists.

Many organic compounds are contaminated with water when they are first produced. This water has to be removed to end up with a pure sample - and separating two mixed liquids is not always easy. The answer is often to add a drying agent - typically a solid that absorbs or reacts with the water, removing it from the mix. The solid is then allowed to settle out, taking the water with it. And one of the best drying agents around is magnesium sulfate. With each magnesium ion able to hold on to seven water molecules, it has a high capacity to extract water, and it works quickly and effectively. The only potential problem is that magnesium is a strong Lewis acid, making magnesium sulfate reactive with some organic compounds.

Nowadays few of us are inclined to take doses of Epsom salts for our health, but the hydrated form of magnesium sulfate has proved much more versatile than a mechanism for making spring water taste foul. Perhaps the best known use is in the bath. Epsom salts frequently form a component of bath salts, where they are supposed to make for a relaxing soak - and surprisingly they could also have health benefits.

Magnesium is an important trace element, which plays a role as an electrolyte, regulating enzymes in the body, but it appears to be deficient in most Western diets. It might seem unlikely that this deficiency could be helped out by having a long soak, but research at the University of Birmingham has shown that regular bathing in Epsom salts increased levels of magnesium by around 40% in the blood and around 100% in the urine, suggesting that Epsom baths really do provide benefit.

There is also an uptake of sulfates in the process, which are thought to lessen discomfort in those suffering from rheumatoid arthritis and muscle pains - so bathing in Epsom salts seems to be a relatively rare case where a traditional treatment is more than a placebo.

Magnesium sulfate has also proved effective in the garden to top up low magnesium levels, which can stunt the growth of plants like tomatoes, roses and peppers. In general, magnesium is important in horticulture both in supporting seed germination and in the production of chlorophyll and fruit.

Epsom salts are not the only type of hydrated magnesium sulfate - it also forms hydrates with one, two, five, six and even eleven water molecules. Kieserite, which has a single water molecule for each magnesium ion, is the next best known example. This is a naturally occurring mineral found in deep deposits, primarily in Germany. It is unstable in damp air, converting easily to more hydrated forms. There is evidence of kieserite and other magnesium sulfate hydrates on Mars, which some believe would be a potential source of water for any future colonization of the planet.

One of magnesium sulfate’s less well known properties is as a sound absorber in the sea. Pure water does absorb some sound, but two relatively scarce compounds have the biggest effect converting the acoustic energy into heat. The two are magnesium sulfate and boric acid, with the magnesium sulfate dominating at all but very low frequencies.

It is possible to manufacture Epsom salts by reacting sulfuric acid with magnesium carbonate or magnesium oxide, but they are usually obtained from natural deposits, while the anhydrous drying agent used in labs across the world is produced by heating hydrated forms. Industrially, magnesium sulfate is electrolysed with a copper anode to produce copper sulfate, and is employed in small quantities in producing beer to adjust the brewing process.

Epsom salts have proved remarkably robust as a treatment for aches and pains. And though Bath and Tunbridge Wells soon eclipsed Epsom as fashionable spa towns for English gentlefolk, for organic chemists, the drying properties of magnesium sulfate mean that it is still one of the best ways to take the waters.

Meera Senthilingam

Science writer Brian Clegg there with the salty chemistry of magnesium sulfate. Next week, Brian returns but things get bitter.

Brian Clegg

Its claim to fame is simple, unpleasant but valuable - denatonium benzoate is the most bitter substance yet discovered. This unreactive, colourless, odourless compound was first produced accidentally in 1958 by Scottish pharmaceutical manufacturer T & H Smith, later Macfarlan Smith, where researchers were experimenting with variants of an anaesthetic for dentists called lignocaine.

It was soon discovered that just a few parts per million of denatonium benzoate were enough for this aggressively unpleasant compound to render a substance distasteful to humans.

Meera Senthilingam

And discover the chemistry behind this in next week’s Chemistry in its Element. Until then, thank you for listening. I’m Meera Senthilingam.

No comments yet