Meera Senthilingam

This week a colourful element with a multitude of uses. Bringing you the luminous chemistry of terbium, here's Louise Natrajan.

Louise Natrajan

As a synthetic chemist whose job it is to study the chemistry of the lanthanide ions, I am often asked which one is my favourite. This is not however a particularly easy question to answer, and my reply often varies depending on which element I have been playing with in the lab that week. You see, although a common perception is that lanthanides all have the same chemistry, and some have even described them as 'boring', each element has its own unique and special characteristics.

Terbium, element number 65, is no different and lies in the middle of the lanthanide series in between gadolinium and dysprosium. It is one of the rarer rare earth elements, although it is still twice as common as silver in the Earth's crust. It is also one of the four lanthanide elements that are named after the place of its discovery, Ytterby in Sweden, 'the village of the four elements'. Terbium was first isolated after several of the other lanthanides in Stockholm, Sweden by Carl Gustav Mosander in 1843, who suspected that the mineral Yttria discovered previously in 1794 by Johan Gadolin might harbour other elements, just as ceria had done previously. Mosander was Professor of Chemistry and Mineralogy at the Karolinska Institute in Stockholm, and he succeeded in showing that yttria was mainly yttrium oxide, but also contained two other oxides, terbium oxide, which is yellow in colour and erbium oxide, which is a rose pink colour.

Compounds of terbium generally contain the terbium ion in its 3+ valence state, however in some solids, terbium is quite unusual in that it can exist in the 4+ valence state, due to the fact its fourth ionisation energy is relatively low so it attains a more stable half filled shell of electrons just as its neighbour gadolinium. The most striking property of terbium compounds comes from its spectroscopic and optical properties, which makes it one of the more exciting and studied lanthanide elements.

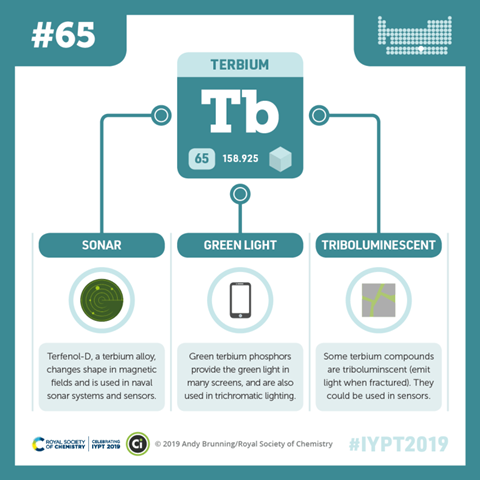

Terbium in the +3 state radiates an aesthetically pleasing luminous green colour when the correct wavelength of energy is used to excite the atoms. This is because terbium 3+ ions are strongly luminescent, so strong in fact, that its luminescence can often be seen by the naked eye The human eye is particularly sensitive to the colour green and even small amounts in the right compound are easily detectable by eye. This bright colour renders terbium compounds particularly useful as colour phosphors in lighting applications, e.g. in fluorescent lamps, where it is a yellow colour, and as with europium(III) which is red, provides one of the primary colours in TV screens; who knew that Tb could be in your TV set! Some terbium compounds are also quite unusual in that they display a phenomenon known as triboluminescence. This is a process where light is emitted when a crystalline solid compound is fractured, so a fracture in the crystalline lattice for example will result in the emission of bright green light that can be seen. The triboluminescence of Tb containing compounds can be exploited in fibre optic sensors that measure changes in mechanical stress e.g. pressure, strains, vibrations and acoustic emissions and has been proposed to be of use in monitoring structural stress in aeroplane wings!

Molecular terbium compounds have also found use in biological and medical research. The green emission of terbium compounds is very long lived, typically in the order of milliseconds, which means it can be detected long after the fluorescence of biological molecules has decayed away, and hence can be used as a biological probe to signal certain events. The luminescence from molecular Tb compounds can be switched on and off by chemical manipulations to the molecule and this has been exploited in the fabrication of sensors that measure the partial pressure of oxygen for example. Other Tb compounds have been used for the determination and quantification of drugs, in DNA and RNA assays, for the determination of protein structures and probes are currently being developed for in vitro cell imaging to aid in the early detection and treatment of diseases including cancer. Finally, Tb phosphors are also used as security inks and are found in anti counterfeit Euro bank notes, although europium is perhaps a little more famous for this role.

Besides its fantastic green colour, terbium also finds a niche role in its use in an alloy called Terfenol-D. Terfenol-D is an alloy of Tb, Fe and Dy and is a material that changes shape in a magnetic field; so called magnetostriction. It is used commercially in a speaker called the 'SoundBug', which turns any flat surface into a speaker! The device works by vibrating any material onto which it is placed such as a table or desk, making it into a speaker.

So what do TV screens, Euro bank notes, triboluminescence and SoundBug speakers all have in common? Terbium of course! So, now when someone asks me which lanthanide is my favourite, I'd have to say that terbium is definitely one of them and it is certainly far from being boring!

Meera Senthilingam

No, not boring at all if it helps make television, sound speakers and currency come into existence. That was Manchester University's Louise Natrajan explaining the many uses of terbium. Now next week a special treat, as we have an element that's so new that it hasn't even officially been named yet.

Sigurd Hofmann

In 1996 we set about producing element 112, inside a particle accelerator. We bombarded a lead target – that has 82 protons – with a zinc beam containing 30 protons for one week, and were able to detect a single atom of an element with 112 protons: Element 112.

Meera Senthilingam

And Sigurd Hofmann, one of the discoverers of element 112 will be explaining the chemistry of this new element and also reveal what he and his team at the GSI Helmolt Centre for Heavy Ion Research in Germany are hoping to name it. So to find out, join us on next week's Chemistry in its element. Until then I'm Meera Senthilingam from thenakedscientists.com and thank you for listening.

No comments yet