Under the shadow of political turmoil and major lawsuits, the industry returned to its strengths – making new drugs, and finding new ways to do it better

Despite the political uncertainty swirling around in 2019 – from Brexit failing to happen twice to Donald Trump’s trade wars – it’s been largely business as usual for the pharmaceutical sector, with mergers, acquisitions and new product launches surrounded by ongoing concerns over pricing.

But perhaps the biggest global pharma headlines were reserved for the US opioid epidemic. The first of many cases against opioid makers and sellers to reach court ended up in defeat for Johnson & Johnson (J&J). The judge in Oklahoma awarded the state $572 million (£475 million) in damages for the harm caused by inappropriate marketing of its opioid products. Purdue and Teva had already settled in the same case.

A federal trial was averted in October, with manufacturer Teva plus three distributors all settling out of court just before the trial. The distributors will pay a total of $215 million, while Teva will pay $20 million plus donate $25 million of generic Suboxone (buprenorphine, naloxone), which is used to treat opioid addiction. Several thousand lawsuits are still pending around the country.

In September, Purdue Pharma – widely seen as the originators of the epidemic, having heavily promoted opioids for chronic pain – filed for bankruptcy as part of a proposed settlement of all the litigation. However, this was structured in such a way that it shields much of the fortune of the company’s controlling Sackler family from plaintiffs.

On the mergers front, two of the biggest deals in recent years were agreed by US-based companies. First, Bristol-Myers Squibb (BMS) acquired Celgene for $74 billion. It had to sell off Celgene’s psoriasis drug apremilast (Otezla) to Amgen for $13 billion to meet competition requirements, as BMS has another drug for the condition in Phase 3 clinical trials.

Then AbbVie bought Allergan for $63 billion, three years after Pfizer’s proposed acquisition of the Irish company fell through. A strong driver for the deal was the expected revenue loss from the expiry of adalimumab (Humira)’s US patents in 2023. Auto-immune antibody treatment Humira currently makes up significantly more than half of AbbVie’s income.

There were multiple smaller deals, including Roche moving into the burgeoning gene therapy field with the acquisition of Spark Therapeutics, gaining its portfolio of potential treatments for blindness, haemophilia and neurodegenerative diseases. Lilly expanded its cancer portfolio with the $8 billion acquisition of Loxo Oncology. And Merck & Co bought Peloton Therapeutics for $1.1 billion, gaining access to its candidate drug for kidney cancer.

Pfizer has done a deal with Mylan to combine the generics manufacturer with its own Upjohn established medicines division under the name Viatris; the Sandoz generics business of Novartis is buying Aspen’s Japanese operations for $330 million to increase its presence in the Japanese market; and Takeda has sold some of its portfolio to Swiss firm Acino for more than $200 million.

Manufacturing and tracking

Chinese contractor WuXi is investing nearly $400 million in its first vaccine manufacturing facility outside China. The facility is being built in Dundalk, Ireland, and is expected to be operational in 2021. GlaxoSmithKline (GSK) is to spend $120 million expanding its manufacturing facility in Upper Merion, US, and spent a similar sum on a continuous manufacturing facility at its Jurong site in Singapore.

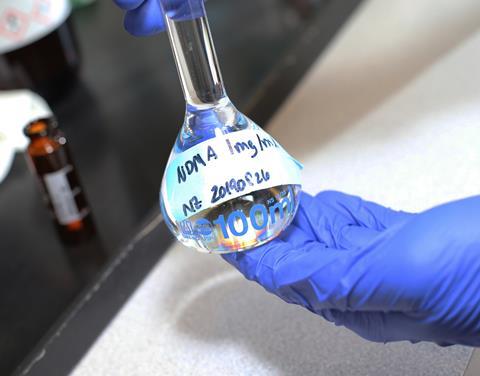

Several drugs have been beset by contamination problems. Traces of carcinogenic nitrosamine compounds were first detected last year in the blood pressure drug valsartan, and subsequently in various other sartan drugs. This September, low levels were also found in antiulcer drug ranitidine.

With multiple generic products from numerous companies having been withdrawn, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) released a list of drugs it believes are free from the contaminants. Although the levels are largely very low, manufacturers are being advised by the regulators to assess their manufacturing processes for all chemically synthesised active ingredients to ensure no nitrosamines are produced.

The Falsified Medicines Directive was enacted in the EU in early February, with the aim of making it more difficult for fake products to make it onto the market masquerading as the real thing. All drug packs now have to carry an antitampering device, and a 2D code that is specific to that individual pack. This will allow it to be authenticated and tracked throughout the supply chain.

Products and pricing

The autoimmune disease treatment adalimumab (Humira, made by AbbVie and Eisai) remains the world’s biggest selling drug, but its 2018 sales of $20 billion represent its first ever decline as biosimilar competition entered the market in Europe. The patents don’t run out until 2023 in the US, when analysts GlobalData predict it will be overtaken by another monoclonal antibody, cancer immunotherapy pembrolizumab (Keytruda from Merck & Co and Otsuka), whose 2018 sales were a shade over $7 billion.

The market for gene therapy products is set to grow significantly, despite the concerns over costs. According to figures from Big Market Research, it’s predicted to reach $4.4 billion by 2023, from global sales of $584 million in 2016 – a compound annual growth rate of 33%. Little wonder that a huge amount of effort is being put into the field. Mustang, for example, claimed its MB-107 gene therapy has cured 10 children with X-linked severe combined immunodeficiency, or ‘bubble boy’ disease.

The costs involved in development mean collaborations are common. Australian company Mesoblast, for example, is working with Grunenthal to advance its allogeneic cell therapy for discogenic chronic back pain, while Kite has expanded its technology deal with MaxCyte to address up to 10 targets.

Orphan diseases make for expensive medicines, and thorny questions about whether they are affordable. In the UK, the National Institute of Health and Care Excellence (Nice) has to make difficult decisions about availability and reimbursement once medicines are approved. This year it gave the go-ahead to BioMarin’s cerliponase alfa (Brineura) in Batten disease and two cannabis-based drugs from GW Pharma; signed an access deal with Biogen for its drug nusinersen (Spinraza) in spinal muscular atrophy, and accepted the Novartis–Spark Therapeutics gene therapy Luxterna for inherited retinal dystrophy. However, it rejected ribociclib (Kisqali) from Novartis in some forms of breast cancer, and the Scottish Medicines Consortium ruled against Kymriah (tisagenlecleucel), the company’s cell therapy lymphoma treatment.

The high cost of Vertex’s cystic fibrosis drugs also caused controversy this year. Five deals with various parts of the UK National Health Service (NHS) have eventually given patients access to Symkevi (tezacaftor, ivacaftor), and Orkambi (lumacaftor, ivacaftor).

In the US, meanwhile, Donald Trump proposed that the US should use reference pricing to determine what the federal programmes Medicare and Medicaid would pay for drugs. This would set prices based on those negotiated in countries including the UK, Germany and Canada. Currently, companies are largely free to set their own prices, and drug costs in the US are notoriously high compared to elsewhere in the world.

Various new drugs gained market approval. Notable introductions include the monoclonal antibody romosozumab (Evenity) from Amgen and UCB to treat osteoporosis, and Sanofi’s dupilumab (Dupixent) was approved for severe asthma. Andexanet alfa (Ondexxya) from Portola was approved to reverse the effects of blood thinning drugs such as apixaban and rivaroxaban in the case of a bleeding emergency.

Rare diseases continue to receive a lot of attention, and several orphan drugs to treat them reached the market. These include volanesorsen (Waylivra) from Akcea and Ionis to treat familial chylomicronaemia syndrome, where patients cannot break down lipids. And a new gene therapy, Zynteglo from Bluebird Bio, treats patients with beta-thalassaemia.

Sometimes drugs for serious diseases are given conditional approval on the basis of early clinical trials results; if they do not prove effective once longer-term data are available, they are then withdrawn. This happened to Lilly’s soft tissue sarcoma treatment olaratumab (Lartruvo) this year, after it showed no benefit in longer term use.

In the world of neglected diseases, advances have been made in Ebola. Experimental vaccines from Merck & Co and J&J are being tested in the Democratic Republic of the Congo. GSK, meanwhile, has shifted its Ebola vaccine research to the Sabin Vaccine Institute, including a vaccine candidate that has already been evaluated in Phase 2 trials.

An experimental tuberculosis (TB) vaccine from GSK showed promise in a trial in Africa. And J&J said it plans to spend more than $500 million over five years to assist in meeting the World Health Organization’s aim to eliminate TB and HIV by 2030. It is also planning a second trial of its investigational HIV vaccine.

Research investment

Pharma remains a very high investor in R&D, with a study from the Campaign for Sustainable Rx Pricing indicating that, on average, companies invest 22% of their revenues back into research. But some areas are fraught by high expenditure and low success rates, not least neuroscience.

Amgen became the latest company to back away from this notoriously difficult field, announcing at the end of October that it is stopping all neuro research aside from neuroinflammation, with the loss of 180 jobs. The decision follows the failure in clinical trials a few months earlier of the beta-secretase 1 inhibitor it was developing with Novartis for Alzheimer’s disease.

Lilly also reduced its neuroscience efforts, announcing plans to close its Erl Wood research unit in Surrey, and shifting its remaining research in the area to Cambridge, US, with 80 job losses. Biogen and Eisai stopped two late-stage Alzheimer’s trials of the antibody aducanumab, but a re-reading of the trial data led to the companies planning to seek regulatory approval regardless.

The availability of – and ability to understand – rapidly growing amounts of genetic data will have a significant impact on pharma research in future. A £200 million whole-genome sequencing project in the UK plans to sequence the genetic code of half a million volunteers at the UK Biobank in Stockport. Non-profit Health Data Research UK, meanwhile, is setting up data hubs that will allow pharma companies, medics and academics access to NHS patient data. Researchers will be able to use large-scale anonymised data to study genetic and lifestyle factors associated with disease.

Several deals have been made between pharma and specialists in artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning. Sanofi, for example, signed up with Google to try and speed up research into personalised treatments via emerging data technologies. China’s Jiangsu Hansoh and San Francisco-based AI specialist Atomwise signed a deal worth up to $1.5 billion to look for treatments acting at up to 11 target proteins.

Novartis signed a deal with BenevolentAI to look for new uses for existing cancer drugs. Bristol-Myers Squibb signed up with Concerto HealthAI to use its machine-learning technology to accelerate clinical trials. Celgene signed up to a three-year collaboration with Exscientia for its AI-driven drug discovery platform. And Merck KGaA is to use AI technology from Iktos in its drug discovery efforts.

Big data is set to be a key enabler in the development of ultra-targeted therapeutics, with advances in genomic sequencing, data sciences and artificial intelligence/machine learning all playing a part. As Arthur D Little stated in its Future Health report, ‘Our ability to create biological data sets specific to individuals and small groups will provide us with incredible insight into patients’ biological make-ups.’ And this insight will be invaluable in creating the medicines of the future.

No comments yet