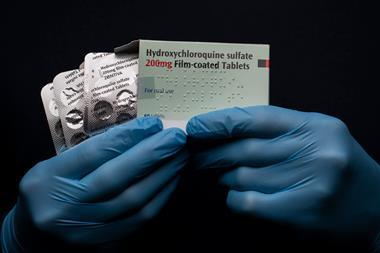

In last week’s podcast on chloroquine and hydroxychloroquine, I briefly mentioned that the World Health Organisation had added these drugs to a shortlist for clinical trials in Covid-19 patients. The Solidarity trials, as they’re now known, are taking place globally and hope to recruit several thousand patients to ensure robust results. In Chemistry in its element this week, we’ll take a look at another of those drugs: remdesivir.

This antiviral earned its place in the Solidarity trials, much like chloroquine, by demonstrating effectiveness against other human diseases caused by coronaviruses, notably Sars – Severe acute respiratory syndrome – and Mers – Middle East respiratory syndrome. It’s also shown promise in treating feline infectious peritonitis, a fatal condition in cats caused by, you guessed it, a coronavirus.

Remdesivir interferes with the RNA that viruses use to replicate. When administered, it is metabolised into a nucleotide analogue – structurally very similar to adenosine, one of the essential building blocks of RNA. Its similarity allows it to compete with the real thing, without performing the same function. This reduces the ability of the virus to make new copies of its own RNA by inhibiting an enzyme called RNA-dependent RNA polymerase. Targeting this process is particularly effective against RNA viruses – those that only use RNA as their genetic material, with no DNA stage. For this reason, remdesivir is considered a broad-spectrum antiviral – diseases caused by RNA viruses include the common cold, influenza, rabies and, of course, Covid-19.

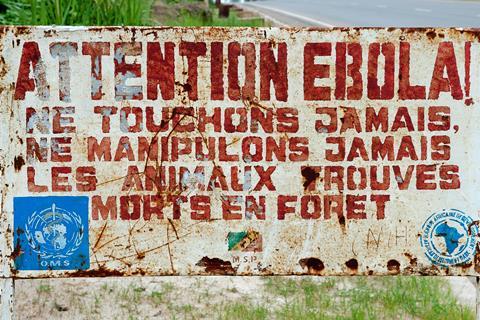

But the Covid-19 pandemic is not the first disease outbreak where remdesivir has been considered. It was initially developed by American biotech company Gilead as a treatment for Ebola, and tested during the Ebola epidemic in West Africa between 2013 and 2016, now considered to be the most widespread outbreak of the disease ever recorded. In a letter published in Nature in 2015, Gilead researchers reported that intravenous remdesivir resulted in ‘profound suppression of [Ebola virus] replication’ in rhesus macaques.

That outbreak saw a new urgency in our approach to clinical trials, and remdesivir was tested in parallel with other candidates in similar approach to the Solidarity trials now underway for Covid-19 – comparing the four most promising treatments. Unfortunately for remdesivir, monoclonal antibody drugs came out on top in those tests, but the trials did increase our understanding of the mechanism of action and the safety profile in humans.

In January of this year, Gilead began testing remdesivir against Sars-CoV-2, the coronavirus that causes Covid-19. The drug inhibited the virus in human cell lines, and Gilead supplied the drug for research in China, before announcing two of their own phase 3 clinical trials in February, with plans to enrol around 1000 patients. The company has also made the drug available for compassionate use in emergency situations, including to a man from Washington State who seems to have been the first confirmed case on US soil. While a growing collection of positive stories stemming from compassionate use is heartening, Gilead themselves state that ‘individual compassionate use cases are not sufficient to determine the safety and efficacy of remdesivir in treating Covid-19, which can only be determined through prospective clinical trials.’

The first of the two trials will target people with severe Covid-19 infections, giving remdesivir intravenously daily for five or ten days and observing clinical markers including temperature and the amount of oxygen in a patient’s blood, known as oxygen saturation. The second trial will focus on patients with more moderate disease. The results from these, in addition to other ongoing trials, will ultimately be considered alongside the World Health Organisation’s Solidarity trial data.

It’s certainly still possible that, as with Ebola, remdesivir may turn out not to be the best treatment available, but the trials play an essential role in helping us to bring together a truly evidence-based picture of which treatments do work, and to put in place a robust global response to Covid-19.

We still don’t know where we’ll be with Covid-19 in a week’s time, so once again I’ll leave the next podcast as an open prospect. We’ve made all of our coronavirus content freely available at chemistryworld.com/coronavirus, but you can also peruse pre-pandemic podcasts at chemistryworld.com/podcasts. Do let us know if there are any compounds in particular that you would like to know more about – email chemistryworld@rsc.org or tweet @chemistryworld. I’m Ben Valsler, thanks for joining me.

Additional information

Theme: Opifex by Isaac Joel, via Soundstripe

Additional music: Illuminate and Serene by Chelsea McGough, via Soundstripe

No comments yet