With media-fuelled anxiety over bisphenol A continuing to rise, Nina Notman looks beyond the headlines at this incredibly widely used polycarbonate monomer

With media-fuelled anxiety over bisphenol A continuing to rise, Nina Notman looks beyond the headlines at this incredibly widely used polycarbonate monomer

One in a million

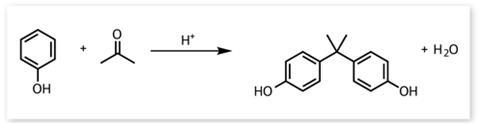

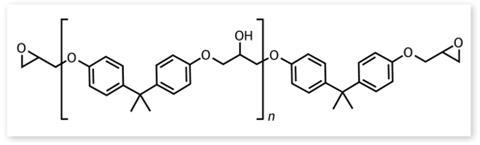

The primary use for BPA is as a component monomer of polycarbonates. ‘The particular structure that it gives is very clear, and that is unusual in plastic,’ explains Galloway. Uses range from water bottles to CDs, cell phones, car parts, medical devices, safety goggles and the list goes on and on. According to PlasticsEurope, an association representing European plastic manufacturers, polycarbonate technology contributed €37 billion to the EU in 2007. And they state that more than 550,000 jobs in the EU depend – either directly or indirectly – on the production and use of polycarbonate.

This all adds up to a unique monomer with no competition in terms of the properties and cost of its polymerised products (see box below). BPA sounds perfect, but is it? Once polymerised there is still a small amount of the component monomer floating around in the plastic: all polycarbonates and epoxy resins contain a small amount of unreacted BPA that will leach out slowly, especially when heated. And BPA is known to be an endocrine disruptor, which is where the controversy starts.

‘There have been a lot of studies in recent years which have suggested that at very low concentrations – within the regulatory limits for human exposure – you can actually see BPA causing a number of different effects that are quite similar to oestrogen,’ explains Galloway. Additionally, human exposure to BPA is incredibly widespread. A survey conducted by the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention between 2003 and 2004 found detectable levels of BPA in 93% of the US population aged six or above.

So why not ban or heavily restrict its use? Well, this body of research is not without its own controversies and regulators across the world – with the notable exception of France – are not currently satisfied that BPA is harmful enough to warrant further restrictions. But huge volumes of research into BPA’s safety are ongoing, and many other countries are keeping an open mind as to whether further controls will be needed in the future.

Booted out of baby bottles

But while the EU’s stance on the safety of BPA remains unchanged at present, since June 2011 the sale of baby bottles made from this monomer has been banned in the region. ‘The decision to ban BPA in baby bottles was based on scientific uncertainty – even if the risk to human health has not yet been demonstrated,’ explains Federica Castoldi.

Europe was not alone in taking such a cautious approach towards newborn health and BPA. ‘Canada was the first country to take action against BPA in baby bottles,’ says Gary Holub, a spokesperson for Health Canada. ‘In 2010, the government passed regulations that prohibited the advertisement, import and sale of polycarbonate baby bottles that contain BPA.

‘In 2008, the government of Canada found that a main source of exposure to BPA came from migration into hot or boiling water placed in polycarbonate baby bottles,’ Holub says. ‘Health Canada scientists did not recommend action on all products containing BPA since science indicates that exposure to the general population is very low, and that most uses of products containing BPA pose little risk to Canadians,’ he adds.

A similar stance has more recently been taken by the US, with plastics made from BPA banned in baby bottles since June 2012. The catalyst for this was a little unusual: it came at the request of the American Chemistry Council (ACC), a trade association representing the chemical industry. Curtis Allen, a spokesperson for the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA), explains that the ‘ACC stated publicly that it filed the abandonment petition to foster consumer confidence in industry’s commitment to stop using BPA-based polycarbonate resins in these products’.

But when it comes to applications other than baby bottles, BPA is still being used as it always has been. ‘The FDA does not have sufficient evidence at this time to show harm to humans at low levels of exposure to BPA and is therefore unable to justify repealing current regulations,’ says Allen. But, as in Europe and Canada, the FDA has expressed some concerns and BPA’s risk is being constantly reassessed.

Unsurprisingly, this move has angered the chemical industry, according to PlasticEurope’s spokesperson Jasmin Bird. ‘Industry expresses significant disappointment and concern at the French Senate [decision] to restrict BPA in food packaging and in medical devices. The French Senate’s adoption, on 9 October 2012, of a law proposal to impose a use-restriction on all BPA-based food contact packaging in France from 2015 is not supported by the current weight of scientific evidence and is in conflict with the opinions of the EFSA,’ she says.

Dose matters

Much of the scientific controversy surrounding BPA is linked to the ‘low dose effect’. ‘Endocrine disruptors may have more important effects at low doses, similar to what hormones would be working at,’ explains Scott Belcher, a professor of pharmacology at the University of Cincinnati in the US. ‘That doesn’t fit into the model where we take lots of BPA – milligrams and milligrams – and feed it to animals and then they develop toxicity [as is done for regulatory testing]. We just don’t see effects at very high doses.’

At present, regulatory frameworks do not take into account the possibility of low dose effects, a fact that is causing some scientists to fear their research is being ignored by the regulators. ‘There seems to be so much evidence of low dose effects and the perception that some scientists have had is that the industry regulators have ignored their evidence. Then what some of the industry regulators have said is that your scientific evidence is not in the right format for us to look at in a regulatory point of view,’ explains Galloway. ‘I think we are getting somewhere now: everyone seems to be talking to everybody else.’All the safety authorities in the world have evaluated BPA

The sign of progress ahead is something Belcher agrees with. ‘Trying to put [the research] into a regulatory and a safety framework is very difficult and that is something we may be able to make some headway on in the near future,’ he says.

In fact, changes to regulatory processes to allow for low dose effects to be considered – for all chemicals, not just BPA – is what Belcher hopes will be the chemical’s lasting impact. ‘Whether or not we make a small adjustment to what we consider to be the safe dose or whether it is banned completely is not the most important question here, because there are thousands of [oestrogen-mimicking] chemicals that we don’t know about,’ he says. ‘So how can we look at it as the bigger picture, and have a bigger impact where we are going to be able to address the safety of all these chemicals. That is going to be BPA’s legacy, in my opinion.’

But this is not an opinion shared by PlasticEurope’s Bird. The low dose effect ‘is not confirmed and there is no scientific evidence of proof today. It would be a shift of paradigm if this theory was to be confirmed,’ she says. ‘All the safety authorities in the world have evaluated BPA and have repeatedly looked at all the studies, including ones claiming low dose effect, and they have repeatedly concluded that there is no reason for concern. These conclusions should be respected.’

Bird continues: ‘Because if you continue to question existing high-quality study results, if you question the relevance of the good laboratory practice or the OECD guideline studies, if you question the whole system of “the dose makes the poison” without providing any new, reliable, validated assessment criteria, then what is left to continue to ensure the provision of reliable and safe materials?’

Ongoing research

The US National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences (NIEHS) is one organisation working to bridge the gap between the regulatory studies and research into low dose effects. The NIEHS is currently funding work carried out in the way regulatory studies are normally conducted but ‘covering a much broader dose range than is traditionally looked at in regulatory studies’, explains NIEHS director Linda Birnbaum.

But this work at low doses is just the tip of the iceberg for the NIEHS: ‘We have been studying BPA for almost 10 years,’ says Birnbaum. And in 2009 they were able to fund an additional $14.5 million (~£9 million) of studies thanks to the Recovery Act stimulus package. ‘We’ve had over 100 different studies published as a result, which has greatly expanded our understanding of the many different kinds of health impacts that we can see – not only in experimental animals but in some human cohorts as well,’ says Birnbaum.There are 20–30 papers published every month on BPA

‘There are now several studies demonstrating developmental neurobehavioural effects in children which are associated with exposure to their mothers prenatally,’ she says. Birnbaum goes on to explain that cross-sectional studies, backed up by animal and in vitro data, show effects on the cardiovascular system, and adds ‘there are also associations with obesity and type 2 diabetes’.

The NIEHS is certainly not alone in trying to answer the questions surrounding BPA’s safety. ‘There are 20–30 papers published every month on BPA,’ says the EFSA’s Federica Castoldi. ‘And the number of publications constantly increases.’

For now, regulators are happy to allow BPA to remain in use for a wide range of applications, with the notable exception of baby bottles and food contact materials in France. But with scientists constantly conducting new safety studies, and the regulators repeatedly reassessing their own position, only time will tell whether BPA’s reign as king of the plastic monomers will continue.

Nina Notman is a science writer based in Salisbury, UK

Replacing the irreplaceable

With BPA banned in baby bottles and a ban regarding food contact uses due to come in to force in France, alternatives to BPA-based polycarbonates and epoxy resins need to be found. But this isn’t a simple task. As stated in a 2010 report published by the World Health Organization (WHO): ‘It appears that it will not be possible to identify a single replacement for all uses, particularly for can coatings.’

When it comes to finding a product to replace epoxy resins – especially for lining cans as noted in the WHO report – the issue becomes more technically challenging. Brown agrees: ‘The alternatives to epoxy are very few at this point.’

These problems finding alternatives, according to Brown, have meant that BPA is currently a contentious issue within both the epoxy resin and food industries. ‘Where I see continued discussion around BPA is more with epoxies, specifically the can coatings,’ says Brown. ‘That seems to be where the debate has focused now, less about polycarbonates and more about epoxy.’

Epoxy resins are used to line the inside of metal cans to protect them from corrosion caused by the foodstuff it contains; acidic foods such as tomatoes are particularly problematic. The lining also prevents any interaction between the metal and the food that may affect the taste. ‘This is particularly important in beer, as when in contact with aluminium it will take on a certain taste,’ explains Brown.

Brown knows of just one company – PPG Industries – that has introduced a BPA-free can lining. ‘They have a product that they claim is BPA-free. It’s a very limited introduction for a very specific end use, I don’t think you can make the leap that it is suitable for all cans, certainly not cans that contain tomato-like products that are very acidic.’

The issue of safety crops up here as well, with the WHO report stating that ‘the functionality and safety of any replacement material need to be carefully assessed’. This is not such a problem when the products have been used for years in similar applications such as with polyester and polypropylene, claims Brown. But according to the US NIEHS’s director Linda Birnbaum :‘There is some concern about whether the alternatives are any safer, or are they safe at all?’

No comments yet