The world’s most expensive infrared spectrometer – the James Webb Space Telescope – is unearthing extraordinary exoplanet chemistry. James Mitchell Crow looks to the skies

- JWST’s infrared breakthroughs: The James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) is revolutionising astrochemistry by tracing molecular evolution from interstellar clouds to planet formation, revealing rich chemistry in distant galaxies and detecting potential biosignatures like dimethyl sulfide on exoplanet K2-18 b.

- Exoplanet atmosphere insights: JWST’s unprecedented sensitivity enables detailed infrared spectra of diverse exoplanets, from hot Jupiters to sub-Neptunes, uncovering atmospheric compositions including water vapour, carbon monoxide and sulfur dioxide, while probing the mystery of temperate super-Earths that may lack atmospheres.

- Origins of complex organics: Observations confirm that prebiotic molecules such as methyl formate and ethanol form on icy dust grains around protostars, suggesting cometary delivery of these organics could have seeded life on planets like Earth.

- Chemical diversity in star systems: JWST reveals striking variations in protoplanetary disk chemistry, including carbon-rich environments around low-mass stars with unexpected molecules like benzene, and provides evidence of rocky planet formation around rogue planetary-mass objects.

This summary was generated by AI and checked by a human editor

A long time ago in a galaxy no distance away at all, a cloud of gas collapsing under its own gravity birthed a new star. Around 4.5 billion years later, a tiny portion of the light from that star today powers the costliest, most carefully designed infrared spectrometer array ever assembled – in this solar system, at least.

As the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) observes the universe through its infrared eyes, it is capturing moments in protostar and planetary birth and evolution never previously witnessed.

‘With JWST, we’re following a molecular trail from the diffuse clouds between stars, to denser clouds collapsing to form new stars, to young stars’ protoplanetary disks, to planets themselves,’ says molecular astrophysicist Ewine van Dishoeck from Leiden University in The Netherlands. ‘The overarching question is always, what makes up the chemical composition of new planetary systems – and could they be habitable?’ she says.

For the first time, JWST has observed the earliest phases of planet formation in a system like our own, detecting tiny mineral grains condensing from the hot gases orbiting close to infant star HOPS-315 in the Orion nebula. In JADES-GS-z14-0, the most distant galaxy ever observed, JWST detected unexpectedly rich chemistry in a galaxy so remote that its light took billions of years to reach us – meaning we are observing it less than 300 million years after the big bang. And on potentially habitable exoplanet K2-18 b, a candidate ‘Hycean’ world hosting liquid water oceans, the tentative detection of a potential biosignature, dimethyl sulfide, has been reported.

Beyond detecting extraordinary astrochemical diversity hidden in starlight, JWST is returning stunning images of the universe around us.

Infrared vision

Infrared telescopes are the ideal tool to probe the molecular makeup of the cosmos, explains Eliza Kempton, an exoplanet researcher at University of Chicago, US. At the typical temperatures of planetary system formation and evolution, matter is mostly molecular. ‘Molecules absorb light most efficiently in the infrared, so observing at these wavelengths is exactly where you want to be,’ she says.

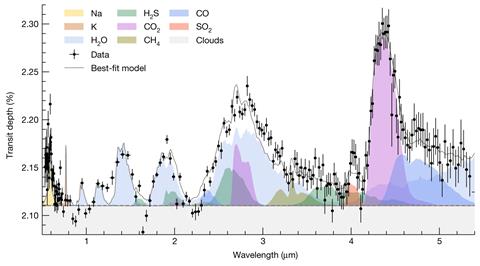

Kempton studies exoplanets orbiting distant stars, building a picture of these alien worlds by probing the chemistry of their atmospheres. The trick is to monitor the host star’s infrared spectrum as the exoplanet passes in front of it. As molecules in the exoplanet’s atmosphere absorb and emit infrared to transition between vibrational energy states, they leave their spectral fingerprint in the light gathered in by JWST’s mirrors. ‘You get a lens right through the planet’s atmosphere,’ Kempton says.

Primarily a theorist, Kempton models how different exoplanets’ atmospheres might appear in the infrared, based on their potential composition. ‘And I try to tie that back to the bigger picture questions – how did these planets form, how did they evolve?’ she says.

Because Earth’s atmosphere attenuates incoming infrared light, infrared astronomy is best done from space. The first exoplanet atmosphere observation was made in 2002, when Hubble’s Space Telescope Imaging Spectrograph detected sodium in the atmosphere of a planet orbiting star HD 209458. The following year Nasa launched JWST’s predecessor, the Spitzer infrared space telescope.

‘I started my PhD when the first exoplanet atmosphere measurements were just being made, for hot Jupiters, the easiest kinds of planets that you could hope to observe,’ Kempton says. These gas giants are about Jupiter-sized but far hotter because they orbit very close to their star.

The bigger and hotter an exoplanet, the easier its atmosphere is to observe. Detecting smaller, cooler, potentially habitable exoplanets’ atmospheres was beyond Spitzer’s capabilities. But with JWST’s launch on the horizon, Kempton started considering what it would take to observe atmospheres of planets more like Earth. ‘Observing planets as small as Earth is really hard, beyond even JWST’s capabilities,’ she says. But the larger rocky planets should be within range. ‘So we thought, let’s go for these bigger super-Earths instead,’ she says.

Once JWST launched in 2021, the step change in sensitivity and resolution over Spitzer was clear from the first spectra. ‘The first scientific dataset was for a hot Jupiter called WASP-39b,’ Kempton says. ‘You could see this beautiful, giant absorption feature in the middle, and I knew immediately, that’s carbon dioxide – even though we had never observed it before – because I’ve run so many models predicting spectra for exoplanet atmospheres.’

Seeing carbon dioxide in a hot Jupiter exoplanet’s atmosphere was a surprise, Kempton says. ‘But it was glaringly obvious – and that was that moment we knew this is going to be great!’

Hydrocarbon haze on sub-Neptunes

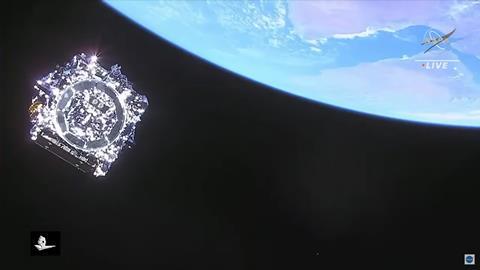

The largest and most complex space telescope ever launched, JWST is the result of an international collaboration including Nasa, the European Space Agency and the Canadian Space Agency.

Nearly five years after launch, JWST’s sensitivity still surprises Alexander Scholz , an observational astronomer at University of St Andrews, UK. ‘We were so used to looking at noisy data with large error bars, where you can’t really tell what you’re looking at,’ he says. ‘With JWST data, often we’re still blown away.’

Size is one factor in JWST’s favour. Compared to Spitzer’s 0.85m mirror, its 6.6m mirror array has a 45 times greater light gathering area. ‘The more mirror you have, the more light you can collect, and that makes it more sensitive,’ Scholz says.

JWST’s recent exoplanet observations, targeting relatively small gas planets called sub-Neptunes, have borne out the initial excitement. ‘There have been several sub-Neptune observations where we see these beautiful, featured spectra,’ Kempton says. ‘They’re diverse, chemically interesting, and probably telling us an exciting story about their atmospheres, their interiors, how they were formed – there’s a lot to piece apart!’

Sub-Neptunes are the most common exoplanet type seen in the galaxy – raising questions about their formation, since our solar system doesn’t have one. Some of the clearest insights yet have come from a sub-Neptune called TOI-421 b, which Kempton targeted because it is unusually hot.

Cooler sub-Neptunes often return featureless infrared spectra, probably due to atmospheric cloud or haze blocking the passage of infrared light. ‘We think these sub-Neptunes – like Saturn’s moon Titan – might be enshrouded by a hydrocarbon haze,’ Kempton says. As methane in these exoplanets’ atmospheres would be photolysed by UV light from its host star, it could initiate a radical cascade resulting in a complex hydrocarbon smog.

In hotter atmospheres, methane’s thermal breakdown should stop haze formation at source. ‘We proposed to look at a hot sub-Neptune expected not to have haze – and it worked,’ Kempton says. Analysing TOI-421 b’s atmosphere, the team found it was rich in molecular hydrogen, like a typical gas giant. They also saw clear traces of water vapour, and tentative signatures of carbon monoxide and sulfur dioxide.

Intriguingly, the team didn’t detect carbon dioxide or methane, which JWST has found to dominate the atmospheres of some cooler sub-Neptunes – such as K2-18 b, a potential water world in the habitable zone of its star. K2-18 b also has hints of dimethyl sulfide, a putative biosignature molecule, in the infrared spectrum of its atmosphere, although this finding requires confirmation.

‘We ultimately want to understand how these planets form – and their atmospheres are the next piece of the puzzle,’ Kempton says. The various theories predicting why the galaxy has so many sub-Neptunes have implications for their atmospheric composition, which Kempton plans to model. ‘We then want to see which of these theories the atmospheric evidence matches up with,’ she says.

Molecular dance on ices

To understand how exoplanets end up with their chemical composition, Robin Garrod at the University of Virginia, US, focuses higher up the molecular trail, at the point where the future exoplanet’s host star is just beginning to form.

Compared with the ultra-cold interstellar medium, where the typical molecule you might encounter is carbon monoxide, star-forming regions are much more chemically interesting. ‘The production of more complex, saturated organics – the kind of thing you might call prebiotic molecules – is particularly associated with star and planet formation,’ Garrod says. ‘The question is, why is star formation so rich in this kind of chemistry?’

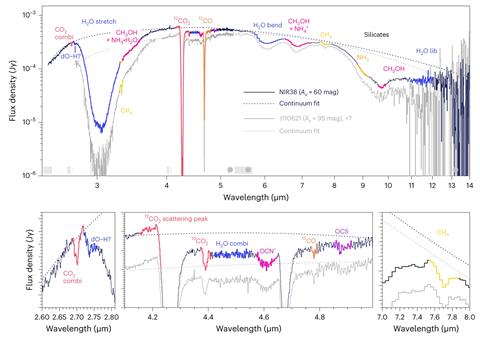

Star formation starts with a centrally condensed cloud of gas and dust. ‘It’s very cold to begin with, so you have this ice chemistry,’ Garrod says. Ices of water, carbon monoxide, carbon dioxide, methane and ammonia freeze out on silicate dust grains. But once the newborn protostar begins to warm its surroundings, the ices start to sublime.

Before JWST, the clearest view of this astrochemistry came from millimetre and submillimetre telescopes, which detect molecules in the gas phase via their rotational transitions. ‘We would see this exceptionally rich gas phase chemistry, telling us that we have a lot of complex organics,’ Garrod says. But it was unclear where these complex molecules came from.

One theory was that they formed by gas phase chemistry, following the sublimation of simple starting materials. Methyl formate is one commonly observed complex organic in protostar gaseous environments, says Garrod. ‘We had ideas for how it could form in a gas phase – but the more calculations and experimental work that was done, the more those ideas fell apart.’

Garrod’s computational studies support the theory that complex organics form on the ices themselves. The mechanism might start with a simple molecule like carbon monoxide, stuck to the ice, reacting with atomic hydrogen – of which space has a ready supply. The resulting radical might meet more atomic hydrogen, to form formaldehyde or methanol. ‘But sometimes, those intermediate radicals will react with each other,’ Garrod says. A new carbon–carbon or carbon–oxygen bond might result.

Because molecules in the solid state are invisible to millimetre and submillimetre telescopes, the idea that complex organics formed on ices couldn’t initially be tested. JWST, however, is perfect for the task. ‘Compared with previous instruments, Webb can analyse these ices with a factor of 100 to 1000 better sensitivity,’ van Dishoeck says. It also has improved spectral resolving power, pulling sharp peaks from previously broad blended spectral features – and confirming complex organics in protostar ices.

Aiming the JWST at iconic star forming clouds such as Chameleon I, and the Pillars of Creation of the Eagle Nebula, returned stunning images – and clear spectra capturing solid-state bends and stretches of ice molecules. Methyl formate, ethanol, acetaldehyde and acetic acid are among the complex molecules van Dishoeck and her team have identified.

Could these complex organics, formed around young protostars long before planets appear, potentially kickstart biological chemistry in these systems down the track? It’s unclear to what extent such molecules might survive the tumultuous phase of planet formation, Garrod says. ‘But we do know these complex organics are preserved in comets,’ he adds.

For a rocky planet such as Earth, formed relatively close to the Sun, even water was likely a scarce resource during its birth. ‘It’s almost certain that impacting comets subsequently brought some water to Earth – but did they bring complex organics too?’ Garrod says. Cometary deliveries might have enabled life on our planet in more ways than one. ‘If you get this kind of chemistry set delivered, rather than having to start from scratch, that could be quite important,’ he says.

Protoplanet chemistry

Beyond ices, JWST is cataloguing the overall chemical inventory of planet-forming disks around stars of different mass and age (and looking at our own solar system; see Backyard astrochemistry below). These observations underscore that the molecular resources available for planet formation vary strikingly from star to star, van Dishoeck says. ‘Just among solar mass stars, some protoplanetary disks’ spectra are incredibly rich in water lines, while others have almost no water but are very bright in carbon dioxide,’ she says.

The biggest surprise in protoplanetary disk composition was delivered in JWST spectra of very low-mass stars. ‘Once you get down to 20% of the mass of the Sun, all of a sudden the chemistry makes a flip,’ van Dishoeck says.

Hints of this chemical shift had been detected by Spitzer, although the data had raised more questions than answers, says Sierra Grant at Carnegie Science in Washington, DC. ‘Spectra from these low mass stars had a weird shape that we didn’t know how to interpret,’ says Grant. With its superior sensitivity and resolving power, JWST solved the puzzle. ‘The spectra still had that shape, but all the molecules popped out on top of it, and all these bumps could now be attributed to carbon-bearing species.’

Organic molecules completely dominate the disk around these small stars. ‘For reasons that we don’t yet understand, these disks have a huge amount of acetylene, almost a factor of 10,000 more than the disks around more massive stars,’ says van Dishoeck. Many complex organics could be identified in the spectra, she adds. ‘We could see diacetylene, the first detection of ethane outside our solar system, the carbon-13 isotopologues of acetylene and carbon dioxide, hydrogen cyanide, cyanoacetylene, propyne and even benzene.’

Benzene is a remarkable find in this astrochemical environment, Grant agrees. ‘That’s a huge ring molecule, and something that I really was not expecting,’ she says. Why these systems are so carbon-rich is a mystery. ‘But it’s telling us a story, and we just have to figure out what it is.’

Perhaps, around these smaller stars, dust settles out sooner and so we see these carbon species just because we have a clearer view into the inner protoplanetary disk, Grant says. Alternatively, because the disks around small stars are cooler and more compact, perhaps all the system’s oxygen – in the form of water ice – falls into the star early in its evolution, leaving carbon to dominate.

‘One of the best ways to test that would be to look at younger systems, to see if they’re full of oxygen,’ Grant says. ‘I’m hopeful, with the next JWST science cycle, that we’ll be able to do that.’

Backyard astrochemistry

At our solar system’s birth, when the Sun was but a fiery young protostar, what astrochemistry was at play as the Earth and its siblings formed?

Noemí Pinilla-Alonso from the University of Oviedo in Spain is leading a team using JWST to reconstruct that period, studying icy remnants of that time. Some of these small bodies were nudged toward the solar system’s outskirts, where they now orbit as trans-Neptune objects (TNOs).

JWST unlocks the capability to interrogate TNOs’ surface composition. ‘Studying their surface tells you the inventory of ices available in the region where they formed, billions of years ago,’ Pinilla-Alonso says. The team selected 54 TNOs for analysis, from 100 to 800km across and with differing visible colour and dynamical properties.

Our conclusion is that each trans-Neptune object class formed beyond a different ice line

Despite this diversity, the objects’ surface composition could be clearly divided into three subtypes. One was dominated by water ice, another by carbon dioxide ice, and the third was a complex mixture that included methanol and more complex organics.

At the time these objects formed, the protoplanetary disk likely had different chemistries in distinct bands moving outward from the young Sun, as temperatures fell and carbon dioxide, then methanol, froze out. ‘Our conclusion is that each TNO class formed beyond a different “ice line”,’ says Pinilla-Alonso. ‘We’re observing a clear snapshot of our solar system 4.5 billion years ago.’

Catching rogue planets

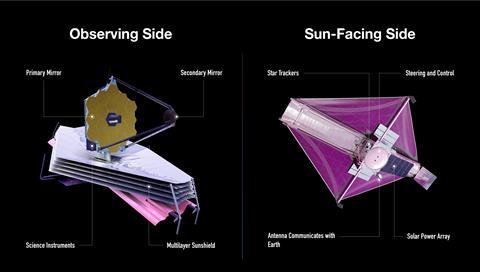

Another factor behind JWST’s high sensitivity is the lengths designers went to supress noise – which, for an infrared observatory, is everywhere in the form of heat. ‘Everything emits in the infrared, so your mirror is suddenly a source of noise, all your instruments,’ Scholz says. ‘You need to keep your telescope very cool, and Webb has a number of innovations that allow that.’

Unlike Hubble and Spitzer, JWST does not orbit Earth but is parked 1.5 million kilometres away in a solar orbit called the L2 point, further from the heat of home and the Sun. JWST also features a multilayer sunshield made of a thin film polyimide, coated with aluminium and doped with silicon to maximise emissivity and reflectivity.

Even heat-generating components of JWST itself, including its computers, solar panels, communications antenna and steering jets, are located on the shield’s sunny side, away from its observing instruments.

While JWST’s hot side sits at a noisy 85°C, its observing side is whisper quiet at –233°C, transforming the research that can be done. ‘Some of the astrochemistry that we have done over the past year only happened because we now have these fantastic spectra,’ Scholz says.

Scholz studies rogue planets – lonely objects of planet-like mass, free-floating in space. ‘Either these objects are giant planets that formed around a star, but somehow got kicked out and are now roaming the galaxy – or, they’re the lowest mass objects that form like stars, from the collapse of molecular clouds,’ Scholz says.

Theory suggests that the fundamental lower mass limit for molecular cloud collapse is somewhere between one and 10 Jupiter masses. ‘With JWST, that’s exactly the mass range we are operating in,’ Scholz says. So far, two surveys have detected a low mass cut-off around five Jupiter masses, and two others have found objects down to one or two Jupiter masses. ‘Either some of us are wrong – missing some of these tiny little dots, or accidentally detecting things in the background or foreground – or we are all correct and you see different results in different star forming regions,’ he says.

These objects are so low in mass, they are too small for fusion reactions ever to ignite in their core, so they will never become stars. They can, however, host orbiting disks of gas and dust like a fully-fledged star – from which little rocky planets might form, Scholz recently showed.

In some of these disks, Scholz found the spectral fingerprint of silicates – some pristine, but some more evolved. ‘That tells you that dust in this disk has started to clump together – which is the starting point of rocky planet formation,’ he says. It’s the first evidence that little planets – or moons – could orbit these planetary mass objects.

What to call such systems is still to be resolved, Scholz adds. ‘We’d like to call them planets rather than “free-floating planetary mass objects”, but they’re not really planets … and the objects that form around them, are those planets, are those moons?’

Naming aside, it is possible these rocky companions might be able to harbour life, Scholz adds – albeit relatively briefly, before the starless system becomes too cold.

Mysterious missing atmospheres

One of the few areas where JWST observations are yet to dazzle is the atmospheres of temperate super-Earths, the most Earth-like exoplanets we might hope to see. But is that because there is nothing to observe?

Compared to sub-Neptunes, super-Earths are smaller and denser, suggesting they are rocky planets with an iron core. ‘Like Earth, Venus and Mars, these planets might have a thin but very interesting atmosphere,’ says Grant. If so, JWST should be able to detect them. ‘We’ve made a lot of measurements, but so far, they’ve indicated that temperate super-Earths don’t have atmospheres. And that is a bit of a bummer,’ Grant says.

That finding might be due to the types of super-Earth analysed so far. ‘A super-Earth passing in front of a Sun-like star is going to block such a small fraction of starlight, it’s going to be really hard to see – so we tend to observe them around smaller host stars,’ says Grant. But these smaller M dwarf stars tend to be very active with lots of flares, UV and x-ray emissions that could strip off an orbiting exoplanet’s atmosphere.

JWST was launched so accurately into its orbit that it still has plenty of fuel still on board

‘There should be a dividing line – a “cosmic shoreline” – between super-Earths that have and haven’t retained a primordial atmosphere,’ says Grant. ‘But we’re not good at predicting exactly where that line is.’ Trying to pinpoint that boundary is the biggest target in exoplanet research right now, she says.

In the meantime, super-Earths without an atmosphere might reveal something about their planetary surface. ‘Different rock types can have different spectroscopic signatures,’ says Grant. ‘It’s a subtle effect, but if we make enough sufficiently precise measurements, we might be able to distinguish them.’

Hopefully, we still have plenty of time to study temperate super-Earths, van Dishoeck says. ‘When I started working on JWST 25 years ago, in the team that built the mid-infrared instrument, we designed it for a five-year lifetime, with perhaps another five years on top of that,’ she says. ‘But Webb was launched so accurately into its orbit, it used almost none of its fuel for course corrections, so has plenty of fuel still on board.’ With luck, JWST might keep going another 15 years, she says.

To tell the full story of star and planet formation, that long lifetime could be key. ‘Because we cannot follow a star system through millions of years of evolution, the only way to complete the story is to study multiple systems in each age band,’ van Dishoeck says. ‘We now have a handful of sources in each band – and we’re literally just scratching the surface of what Webb can do.’

James Mitchell Crow is a science writer based in Melbourne, Australia

No comments yet