From structure confirmation to methodology improvements, making complex natural products has driven innovation in organic synthesis for decades. Nina Notman looks at its current state, with threats from funding to academic pressures

- Evolving goals in total synthesis: Originally focused on structure confirmation and producing scarce natural products, the field now emphasises efficiency – shorter, more inventive synthetic routes that inspire new methodologies and drug development.

- Technological and methodological advances: Innovations include radical cross-coupling, domino reactions, enzyme cascades and late-stage diversification strategies, enabling faster access to complex molecules and derivative families.

- AI’s emerging role: While creativity in route design remains human-driven, machine learning and quantum-informed tools are being developed to predict selectivity and improve computer-aided synthesis planning for complex molecules.

- Challenges and future outlook: Despite pharmaceutical interest in complex molecules, funding declines, academic metrics and regional disparities threaten the sustainability of total synthesis research, raising concerns about training future medicinal chemists.

This summary was generated by AI and checked by a human editor.

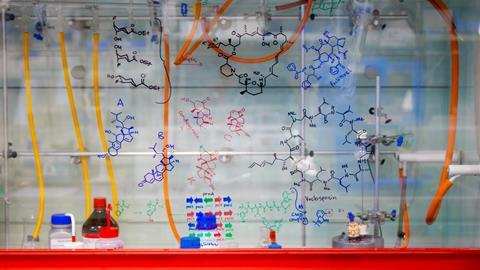

‘I went into this field because I read the book written by Stuart Warren about retrosynthetic analysis. It’s written in such a beautiful way [that it made me] fall in love with total synthesis,’ explains Jieping Zhu from EPFL in Lausanne, Switzerland. The book he is referring to is Organic Synthesis: The Disconnection Approach, and it outlines how to plan a synthetic route by starting with a drawing of the target molecule’s structure and imagining breaking its bonds one-by-one until easily available starting materials are reached. It’s like looking at a fancy wedding cake and trying to figure out what ingredients and processes could be used to replicate it. The concept of retrosynthetic analysis was first formalised by E J Corey in the 1960s and ever since then, organic chemists have been sitting in team meetings debating the best ways to disconnect the bonds in the molecules that they want to synthesise.

Natural products are metabolites produced by living organisms; they are relatively small molecules – compared to enzymes and proteins – with extremely diverse structures that are typically 3D and very complex. ‘Natural products tend to be polycyclic with lots of stereochemistry,’ says Sarah Reisman from the California Institute of Technology in the US. Complex small molecules can theoretically be deconstructed in a myriad of ways. But turning one of these into a viable synthetic route in the forward direction requires strong problem-solving credentials and an abundance of creativity. Natural product chemists are often compared to mountain climbers plotting the best route to a summit.

An evolution of purpose

Chemists have been trying to synthesise natural products in the lab for around two centuries – urea was the first to be made in 1828. Structure confirmation is one reason to attempt a total synthesis, especially so in the early years. ‘Most of the organisms that make these molecules produce them in very, very small quantities,’ explains Nigel Mouncey from Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory in California, US. This makes elucidating their structures challenging, even more so before the advent of modern spectroscopic and x-ray crystallography techniques. By making a sample of the compound with an assumed structure in the lab and comparing its analytical data with that of the natural compound, its structure can be confirmed or corrected. Chemists still sometimes find errors in long-assumed structures during total synthesis projects, especially at stereocentres.

Performing a total synthesis also provides scientists with enough of a molecule to study its biological function and potential medicinal properties. ‘These molecules are not random – they are the result of millions of years of evolution, designed by nature to perform biological processes with incredible precision,’ says Chao Li from the National Institute of Biological Sciences in Beijing, China. It is estimated that around 50% of approved drugs in the EU and US are currently either a natural product or a derivative of one. These include paclitaxel (Taxol), a compound found in the bark of Pacific yew trees that has been extensively used to treat breast, lung, ovarian and other cancers for over 30 years. A more recent example is voclosporin (Lupkynis), derived from cyclosporine A found in the Beauveria nivea fungus; it was approved for use as an immunosuppressant to treat kidney complications from lupus in the US in 2021 and the EU in 2022.

Another common reason academics participate in total synthesis projects is to train the next generation of medicinal chemists. ‘If you talk to any pharma company, the people they want to hire more than anyone else are those trained in the art of total synthesis,’ says Phil Baran, from Scripps Research in La Jolla, California. Problem-solving skills developed during this type of work is one reason, as is the breadth of experience gained – each step in a total synthesis typically requires a different type of chemistry. ‘In natural product synthesis, [students] have the chance to experience many different kinds of organic reactions,’ explains Jinghan Gui from the Chinese Academy of Sciences’ Shanghai Institute of Organic Chemistry

Improved route planning

For many organic chemists, however, the main attraction of total synthesis is the opportunity to add more tools to the synthetic chemistry toolbox. For much of the 20th century, the focus was on being the first to make a target molecule of interest. In recent decades, the goal has evolved into trying to make complex molecules using the shortest route possible. Returning to the mountain climber analogy, organic chemists no longer necessarily aim to be the first ever to reach a summit. Rather, they strive to be the fastest and use the fewest steps. ‘The goal should be an organic synthesis where you only make skeletal bonds and nothing else,’ says Baran. This means a route where each reaction builds a bond or two onto the molecule that is still present in the final product, with no detours (such as protecting groups) needed. ‘To achieve that requires that the practitioner become an inventor ,’ he explains.

The desire to make a complex molecule provides the inspiration to develop novel reactions and strategies, says Rebecca Goss, from the University of St Andrews, UK. ‘It’s just like developing new technologies to prepare for an Everest assault. The inspiration, the muse for developing new synthetic methodologies, [is the potential] to take greater strides up the mountain.’

Baran outlines the importance of these technological developments: ‘Those methods that come out as a consequence of coming up with innovative routes to natural products often find their way into the portfolio of methods that people use to design and invent new drugs,’ he says.

Growing the toolbox

New tools can come in many forms. A favourite category from the Baran lab is radical cross-coupling reactions. Radical retrosynthesis is a less common way to think about disconnecting molecules than polar bond analysis. ‘We’ve all been taught how to make molecules by assigning delta plus and delta minus partial charges to functional groups and then disconnecting between them,’ Baran says. Using a radical cross-coupling instead allows unique disconnections to be made and enables rapid access to complex 3D molecular motifs, he adds. In March 2025, Baran reported that sulfonyl hydrazides can be used to forge a wide variety of carbon–carbon bonds through radical pathways. In August, he demonstrated its utility in the synthesis of saxitoxin, a potent shellfish neurotoxin of interest to the pharmaceutical industry. Using this approach, his group made saxitoxin and related natural products all in fewer than 10 steps.

The Gui group also explores the potential for radical reactions in total synthesis. In February 2024, it reported the first laboratory synthesis of aspersteroids A and B in 15 and 14 steps respectively from commercially available ergosterol. These synthesises had several radical chemistry steps including a diastereoselective radical reduction of an epoxide to install a challenging stereocentre. Earlier attempts at this transformation produced the opposite chirality at this centre to the natural product. ‘It took us over a year to solve that issue,’ says Gui. ‘It was one of the most challenging projects we have worked on.’

Hong-Dong Hao, from Northwest A&F University in Shaanxi, China, also looks to use uncommon disconnection types. In December 2024, his group reported the construction of the four ringed (one six- and three five-membered rings) skeleton of marine cyclopianes with key steps including a gold-catalysed Nazarov cyclisation and Pauson–Khand reaction. Hao completed the asymmetric synthesis of conidiogenones C and K and 12β-hydroxy conidiogenone C, each in around 20 steps. He also collaborated with Houhua Li from Peking university to show that these molecules have anti-inflammatory activity. ‘The Nazarov cyclisation works smoothly on several substrates, and this is a disconnection that is not obvious using retrosynthetic analysis,’ says Hao.

Simplicity is a key goal of other natural product chemists. The Zhu lab bolts together a number of textbook reactions in a domino (also called cascade) sequence to rapidly build complex motifs. These reactions take place in a single pot without isolating or purifying any intermediates. In October 2025, Zhu reported a domino reaction in the first enantioselective total synthesis of (+)-punctaporonin U, a compound that is present in numerous plants including cannabis. It has a cage-like motif with five rings, two bridges and eight stereocentres and the team created it in 11 steps from cyclopentadiene. The domino sequence was a Michael addition, an aldol reaction and then a bromination, to make fused five- and seven-membered rings. ‘This is a very simple strategy using traditional textbook reactions, but when used in combination they allowed us to build this very cage-like structure,’ says Zhu.

An enzyme family business

Domino reactions are also possible using biology’s catalysts: cascades of enzymes can pass molecules from one to another in the style of a factory assembly line. This approach is particularly powerful in the synthesis of families of molecules. ‘We can build out expansive families of compounds using synthetic biology and do it very quickly too,’ says Mouncey.

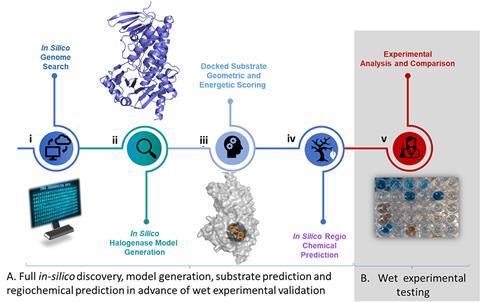

The Goss lab is using enzymes to access derivative families in a different way – by precisely editing complete natural product structures. ‘We are not changing the core structure,’ she says. Her lab uses halogenase enzymes to selectively replace one or more specific hydrogens on the periphery of a molecule with halogen atoms. ‘These enzymes can, with precision, take a carbon–hydrogen [group] to a carbon–chlorine, a carbon–bromine or a carbon–iodine,’ she says. In October 2025, she reported the use of a halogenase from brine cheese to regioselectively halogenate medicinally relevant heterocycles including quinolines, isoquinoline, phenylpyrazole and flavonoids. Since halogens are reactive, these can easily then be substituted with a wide range of functional groups to the periphery of these molecules. ‘You’re limited only by the imagination of the chemist’ when it comes to what to replace the halogens with, Goss explains.

Dale Boger, from Scripps Research, is using chemistry to rapidly access lots of derivatives of natural products for biological testing. ‘We design syntheses where at late stage we can use a common intermediate to access a whole series of structurally related compounds,’ he says. Molecules that Boger has demonstrated this approach with include the antibiotic vancomycin, produced by the soil bacteria Amycolatopsis orientalis. He has been working on modifying this structure for over a decade. His current version has a single altered atom in vancomycin’s bonding pocket, making it active against vancomycin-resistant bacteria while retaining activity against vancomycin-sensitive bacteria (such as MRSA). It also has two peripheral modifications that introduced two mechanisms of action that aren’t present with the natural product. ‘In the end, the molecule has three independent and synergistic mechanisms of action, only one of which is embodied in the natural product. This suggests that it would be almost impossible for bacteria to develop resistance to the antibiotic,’ says Boger.

The Li lab is also working to supercharge natural antibiotics with late-stage chemistry modifications. In September 2024, it reported the synthesis and structure optimisation of kibdelomycin, from the Kibdelosporangium bacteria. This molecule had previously been explored as a potential broad-spectrum antibiotic by Merck. ‘The compound did not progress to clinical trials [and] Merck scientists noted that structural modification would be essential to improve its drug-like properties,’ says Li. His lab took up the challenge, making a number of late-stage modifications to the natural structure. ‘We obtained an improved analogue with stronger antibacterial potency and reduced toxicity — a promising lead compound,’ Li explains.

AI assistance under exploration

AI tools for enabling natural product synthesis are currently being intensively explored. Computers were first used to help with retrosynthetic route planning by Corey in the 1960s but, despite significant advances, this approach still isn’t suited to complex molecules like natural products. ‘We are getting better and better at retrosynthesis [using computer software], but the algorithms still depend, at least right now, on past established chemistry,’ says Reisman, whereas ‘we’re very interested in using synthesis as a motivation for developing new chemistry’. Baran agrees. ‘The key thing here is to remember is that this field still has a high artistic component to it,’ he says. ‘Art needs soul and I’m not aware of any kind of algorithm yet that can code sentience or soul.’

But while the creativity needed to plan synthetic routes to complex molecules remains a human attribute for now, AI is starting to play a supportive role. Reisman is part of the National Science Foundation Center for Computer Aided Synthesis, which brings together synthetic chemists and data scientists to help AI find its place in organic synthesis. ‘What’s important is that we learn how to leverage [computational tools] to enable human creativity,’ she says. In February 2025, Reisman reported the training of machine learning models to predict the site selectivity of carbon−hydrogen functionalisation reactions in complex molecules containing multiple sites with apparently similar reactivity. The ability to do this prevents chemists getting part way through a long synthesis and then realising that the site selectivity needed for a particular step cannot be achieved. ‘This idea is how do we take data driven approaches … to de-risk the challenging steps of synthesis,’ she says. In the paper, she describes using a curated number of literature reactions to train machine learning models that are then able to extrapolate the published information to make accurate predictions as to which carbon−hydrogen group in complex molecules will undergo oxidisation and borylation. This approach, her group reported, was more successful than attempting predictions based on a larger collection of randomly selected literature reactions.

Ryan Shenvi, from Scripps Research, is also using computers to take the guesswork out of total synthesis. In February 2025, he reported a quantum-mechanical and statistically modelling ‘patch’ to improve the effectiveness of existing computer-aided synthesis planning software, and demonstrated its utility in the synthesis of 25 naturally-occurring picrotoxanes. This family of molecules has been found in diverse plant species, with some known to bind to ion-channels in the nervous system of mammals.

Shenvi’s group created this patch after it encountered problems trying to re-use a synthetic route template it had developed to reach picrotoxinin to make other molecules in the same family. ‘This happens quite frequently. You run into reactivity that you can’t explain,’ he says. ‘So, then it turns into this exercise of just throwing everything but the kitchen sink at a molecule to try to it do what you want.’ Computer-aided synthesis planning software assumes that chemical reactions in the literature can be ‘used as a template to assume the reactivity of millions or billions of analogous reactions. This doesn’t work because these are pen and paper approximations of what is a quantum world,’ he explains. ‘The solution to the problem of retrosynthetic computational tools is to have some interface with a quantum mechanical calculation,’ he adds. With the patch, Shenvi generated a virtual library of the intermediates needed to make the various routes suggested by a computer-aided synthesis planner and predicted which were the most achievable to make. ‘We used the computational tools to identify which [route] is best, and therefore try to minimise random experimentation,’ he says.

Challenges to be conquered

On the surface, the field of natural product synthesis appears to be thriving. This is especially true when you consider that the pharmaceutical industry is currently taking a renewed interest in using complex molecules as inspiration for drugs, after a prolonged period using the high throughput screening of libraries of simpler compounds as a starting point instead. ‘I fundamentally see a shift in pharma towards more complex designed compounds that are coming out more sp3 rich,’ says Reisman.

But beneath the surface, they are some major concerns about the health of the field. Most of this is due to changes in the global funding landscape in recent decades, with many saying that the UK has been one of the hardest hit. ‘I’ve seen big groups exit the UK or retire within the UK with no replacement, [as there is not] a massive backing for total synthesis here,’ says Goss.

Research funding in China is now increasingly directed toward emerging or more applied fields

‘I use the UK as the negative example of what happens when you rely too heavily on industrial support of graduate training … to offset changes in federal funding,’ Reisman says. ‘Those industrially sponsored research agreements tend to not be for natural product synthesis,’ she adds. The pharmaceutical industry favours methodology due to the shorter project timelines, Reisman explains – adding that this is counterintuitive as they prefer to hire employees trained in the art of total synthesis.

In recent years, China has bucked this trend with a growing and thriving total synthesis chemistry community. ‘In the past decade, China’s major talent programs and significant investments in basic research have certainly contributed to this growth,’ says Li. But the situation is changing. ‘Research funding in China is now increasingly directed toward emerging or more applied fields, while support for traditional disciplines such as total synthesis has relatively declined,’ he adds. ‘In China, for natural product synthesis it’s [also now] very challenging to get enough funding for research,’ agrees Gui.

The way that academic performance is measured today is another reason why fewer young chemists are choosing to pursue total synthesis projects. The publish or perish culture is incompatible with a field that has long timelines and generates fewer papers than its methodology counterpart. ‘The metrics that we’re using for things like tenure and promotion are very heavily based on publication numbers. This stops folks from strategically wanting to enter synthesis, because we tend to publish fewer papers,’ says Reisman.

‘It is an unfortunate confluence of factors ranging from funders wanting to support projects that generate numerous papers, to universities preferring to hire people with extensive publication records, and natural product synthesis not being amenable to rapid fire publication in the way that methodology development is,’ Baran says.

It’s hard to imagine that organic chemists will completely stop pursuing total synthesis projects, but the reality is that unless the funding situation and academic recruitment metrics change the numbers of these projects will continue to dwindle. When you consider the role of this work in training medicinal chemists and giving them the tools and inspiration to build the drugs of the future, this should be a huge concern for all of humanity.

Nina Notman is a science writer based in Salisbury, UK

Main image is © Edward Broughton/University of St Andrews, with thanks to Sunil Sharma, Jacob Peatfield-Muter, Piyasiri Chueakwon and Rosemary Lynch

No comments yet