RRS Sir David Attenborough scientists are trying to measure the potentially crucial role of ocean manganese, finds Andy Extance. But how do you do cutting-edge science in the inhospitable Southern Ocean?

- Climate and ecosystem concerns: The Southern Ocean absorbs about 40% of human carbon dioxide emissions, aided by phytoplankton and krill. However, climate change threatens this process, with declining krill populations and uncertain phytoplankton growth challenging carbon absorption predictions.

- IronMan project goals: Led by Alessandro Tagliabue, the £4m IronMan project aboard the RRS Sir David Attenborough aims to study the roles of iron and manganese in phytoplankton growth and carbon cycling – elements overlooked in climate models but potentially critical for global climate regulation.

- Extreme sampling challenges: Researchers face harsh Antarctic conditions while measuring trace metals at concentrations as low as a teaspoon in the River Thames. They use specialised titanium equipment, clean labs and advanced techniques to avoid contamination and gather over 1000 litres of seawater samples.

- Broader scientific impact: The project combines chemical, biological, and genetic analyses to understand nutrient recycling, organism metabolism and gene expression. Findings could reshape climate models and reveal how rapid sea ice loss and ecosystem changes affect global climate resilience.

This summary was generated by AI and checked by a human editor

In the Southern Ocean near Antarctica, the head of a young blue whale emerges from the water and unexpectedly moves towards a drone flying above. The subtle movement of recognition excites British Antarctic Survey (BAS) scientists watching nearby on 10-metre-long workboat Erebus, five miles away from its home on Royal Research Ship (RRS) Sir David Attenborough. Blue whales, the largest animals on Earth, are unusual in this area. They have recovered since hunting cut their numbers in the Southern Ocean to around 3000, but no-one knows the extent of their recovery.

Since 2023, BAS researchers have been measuring whale numbers, and the volume of the tiny crustaceans called Antarctic krill that they eat. The blue whale is on video footage from the RRS Sir David Attenborough’s last visit to Antarctica during its spring and summer at the end of 2024 and beginning of 2025. ‘We are concerned with climate change that we’ll see less krill,’ says Stephanie Martin of BAS, project manager on the Hungry Humpbacks project.

As well as affecting whale recovery, climate-driven krill decline would have even broader implications. ‘Whales are a good bellwether species to figure out what’s going on within the habitat,’ says Martin. ‘People like whales, but krill is important too.’

The Southern Ocean, where these whales and krill live, currently absorbs around 40% of the carbon dioxide taken up by the oceans, which themselves absorb about 25% of human emissions. That is helped by microscopic plants in the ocean called phytoplankton that suck up carbon dioxide as they grow. Tiny animals called zooplankton eat phytoplankton. Krill also eat phytoplankton before other creatures, including whales, eat them, naturally capturing carbon.

Yet researchers are uncertain whether this food chain will reliably keep absorbing ever more carbon dioxide. Climate models predict that phytoplankton should prosper as temperatures rise, explains Alessandro Tagliabue from the University of Liverpool in the UK. If this were true it would act as a brake on global heating. But observations ‘appear to show the opposite’, Tagliabue tells Chemistry World.

If creatures in the Southern Ocean absorb less of humanity’s carbon emissions as the planet heats up, that will further accelerate heating. ‘We urgently need accurate climate-model projections to assess the response of Southern Ocean ecosystems and biogeochemical cycles to climate change,’ says Tagliabue.

Therefore, as the RRS Sir David Attenborough’s bright red hull slices through the Antarctic chill in January 2026, Tagliabue will lead a biogeochemical quest. Hidden in the icy blue expanse a surprising chemical culprit might explain how much carbon dioxide the oceans will absorb. Since the 1990s scientists have thought that iron is the key nutrient driving phytoplankton growth. That’s why some people want to add iron to the ocean to fight climate change – but the reality could be more complex.

Overlooked by climate models, the element manganese could be as critical as iron in many parts of the ocean. Get the chemistry wrong, and our predictions for future biodiversity, carbon cycling, and global climate suffer. Tagliabue will therefore lead the £4m IronMan project studying the iron and manganese mystery.

In one of Earth’s most extreme environments, the scientific and practical challenges facing IronMan take on new dimensions. Researchers are measuring tiny amounts of iron and manganese – their concentrations are equivalent to dissolving one teaspoon in the entire River Thames. Yet the team must find the precision to do this amid winds regularly exceeding 60km per hour, sub-freezing temperatures and waves over 10m in height.

Mysterious manganese

Iron has long been thought to be the limiting nutrient that controls how fast organisms in this area turn carbon dioxide to other compounds. Climate models predict that this process, known as primary production, should increase as the Earth heats up, but it has slowed down. The models also overlook the role of manganese, which scientists have recently found to be another factor limiting primary production.

IronMan is now looking to explore the role manganese plays in the Southern Ocean. This will include the fact that Antarctic organisms are uniquely adapted to their environments, and climate models may need to explicitly represent this. Iron and manganese are both predominantly linked to photosynthesis, so it’s important to understand which organisms favour iron, and which favour manganese.

Measuring trace metals in extreme conditions

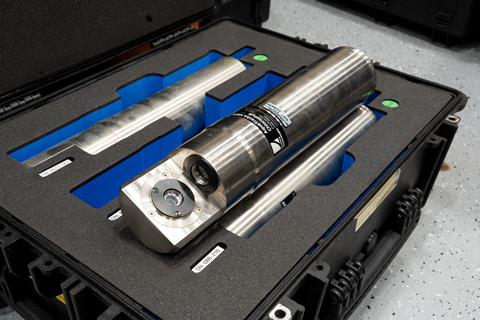

When Chemistry World visits the RRS Sir David Attenborough in dock at Harwich, UK, in October 2025, a cylindrical cage known as a rosette is at the ship’s heart. Several tubular Niskin bottles are mounted on it, each looking like an elongated scuba tank. As crew prepare for the upcoming journey around her, Sophie Fielding, the ship’s science capability coordinator, explains that the rosette also carries a conductivity, temperature and depth (CTD) recorder.

The rosette is what researchers use to sample tiny traces of metals in the sea, so it can’t contain the same metals, Fielding explains. The cage and bottles are therefore made of titanium rather than steel, whose iron content would interfere with measurements. The IronMan team will lower the cage into the ocean using a winch kept in a separate room to ensure it’s contaminant free, Fielding explains. The steel cables that lower the recorder and communicate with it into the water are encased in Kevlar to prevent them releasing contaminants.

The rosette rests on doors above a hole running right down to the ocean, known as a moon pool, in which researchers aboard other ships sometimes play on inflatables, Fielding notes. A moon pool’s primary purpose is to provide a sheltered place to lower the cage. ‘The water can freeze in the bottles if you bring it up in the wind,’ says Fielding. Bringing bottles up inside the ship means that the contents remain liquid, so that researchers can process them quickly.

Studying trace metal chemistry is laborious, because there are no sensors to do it directly in the ocean. Instead, scientists must collect large volumes of ocean water in Niskin bottles, explains Kate Hendry a chemical oceanographer and marine biogeochemist with BAS. They then test it on the ship and back in the UK. Researchers like Hendry process the bottles in a clean lab on the RRS Sir David Attenborough with filtered air and protective clothing to prevent sample contamination. They’ll collect over 1000 litres of samples during the voyage.

In the clean lab, researchers filter out particles larger than 0.2µm from the seawater, explains Lavenia Ratnarajah from University College London. Filtering separates out the living creatures and leaves behind the dissolved elements. Ratnarajah explains that phytoplankton need light and nutrients to grow, just like plants on land. Unlike on land, however, there is usually plenty of nitrogen for them in the Southern Ocean, but not enough iron. New research has shown that manganese could also limit phytoplankton growth, explains Ratnarajah.

The ship can rock dramatically as scientists filter seawater, Hendry notes. ‘It can be blowing 40 knot [75kph] winds, and you can still be sampling and working,’ she says. Just trying to stand up with one hand stabilising herself or her equipment is tiring. ‘You do develop a particular stance working at a laboratory bench in rough weather. You have to plant your feet very firmly, and I usually balance myself by resting my stomach against the laboratory bench whilst using my hands to hold the equipment steady.’

Revealing ocean chemistry secrets – in a lab

By contrast Hendry calls working in 24-hour Antarctic summer daylight ‘amazing’ – even though it can be a mixed blessing. ‘It feels like you’ve got extra energy,’ she says. She sometimes finds herself still working in the lab at 2am. ‘You never really want to go to bed. You have to be very disciplined on yourself and stop yourself and get a proper night’s sleep.’

Deploying the CTD rosette alone can lead to long days. It can contain up to 24 Niskin bottles, which are open when they enter the sea, Tagliabue explains. The researchers can lower them up to 6000m, triggering signals for the Niskin bottles to close regularly as the rosette ascends. Every 1000m of descent (and subsequent return) takes around an hour. A full-depth ‘cast’ will therefore take at least six hours, and the ship has multiple rosettes. ‘When the rosette comes back onto the deck, you’ve got snapshots of seawater collected at different depths,’ says Tagliabue. As well as iron and manganese, the researchers are interested in nutrients like nitrates, phosphates, silicates, plus carbon and oxygen.

After filtering, the researchers store samples for thorough nutrient concentration analysis by mass spectroscopy at the University of Southampton back in the UK. On the ship, researchers use flow injection chemiluminescence, a colour-based method. They compare the colour the system returns with calibrated standards for the nutrients. This helps test whether they are contaminating their samples before they return, so that they can rerun sampling if needed. It also helps the scientists plan their next experiments, Tagliabue explains. ‘Any voyage you go on, I think you’ve got to be prepared that plan A might go out the window,’ he says. ‘You might need to really think on your feet about what exciting science can we do.’

The researchers will also study the creatures that they filter out. They’ll keep some in two temperature-controlled labs near the moon pool, watching how fast ‘primary consumers’ like zooplankton and krill eat phytoplankton, Tagliabue explains. That will help work out whether the current low phytoplankton levels are because more is being eaten. But the IronMan project is also interested in the fact that the primary consumers don’t absorb everything they eat. Tagliabue and colleagues want to measure what they excrete, to see whether that recycles nutrients. Dense faecal material would sink and leave the food chain, but urine could stay in the water, he explains.

Zooplankton should be recycling a lot of their manganese – but we don’t really know

Algae, which include single-celled phytoplankton as well as multicellular seaweed, use enzymes containing iron and manganese, Tagliabue continues. These enzymes help algae photosynthesise and run the metabolic machinery keeping them alive. But the key scientific challenge facing IronMan is that scientists ‘still don’t really understand that’, Tagliabue says.

The project will therefore study how algae and the organisms consuming them use the elements. Much like humans don’t photosynthesise but need iron in haemoglobin to carry oxygen around our bodies, zooplankton also need iron to run their respiratory systems. They may also use manganese in enzymes called superoxide dismutases that mop up free radicals, but the default hypothesis is that they don’t need any manganese. ‘They should be recycling a lot of their manganese,’ says Tagliabue ‘But we don’t really know – there is a massive knowledge gap.’

The IronMan team will also freeze some filter samples in liquid nitrogen for later genetic analysis in the UK to identify which organisms are present. Sequencing will go beyond studying DNA, reading the RNA instructions cells are producing, or expressing, from their core genetic code. This ‘tells us, effectively, what are the organisms trying to do’, Tagliabue explains. If there is lots of RNA related to proteins that help iron uptake, it indicates that the organisms are not getting enough from seawater. There are also proteins that enable photosynthesis without using iron, albeit less efficient ones. If phytoplankton are using the less efficient proteins, it’s evidence that nutrient supply is limited, Tagliabue says. ‘One part of the project is trying to link the availability of iron and manganese in seawater to the expression of different genes.’

Going against the floe

This season, Hendry is based at the BAS research station at Rothera, on an island near the coast of Antarctica closest to South America. As well as sampling the deep Southern Ocean, the shipboard IronMan team is due to meet up with her there. They will go in a small boat to a nearby rapidly melting glacier to study particles coming from the glacier, exploring how that sudden melting might affect organisms. To do this they will lower bottles down to 500m using a hand winch, which is ‘a good way to keep people warm’, Hendry jokes.

Tagliabue is excited by bringing these different experiments together, as that’s never been done in a single voyage before. ‘It’s trying to put all these elements together – no pun intended – which is exciting, but it’ll be challenging,’ he says. ‘Each approach has their own strengths and weaknesses, their own challenges.’ Tagliabue is also wary of psychological challenges from ‘having 40 people trapped in a metal ship for seven weeks’. So he’s looking forward to mooring at Rothera for a few days. ‘It’ll be good, a morale boost for everybody on board to get off.’ And those psychological challenges can be even greater when experiments go wrong.

In January 2018, aboard another ship, the RRS James Cook, Tagliabue was part of a team who had several malfunctions when measuring iron concentrations near deep sea volcanoes. Their CTD rosette even got stuck 3000m under the sea. The ship’s crew generally fix these issues, ‘but equipment malfunction starts to cost you time’, Tagliabue says. If the rosette didn’t work correctly, ‘do I really deploy again and invest another six hours?’, he must ask himself. And sometimes researchers lose equipment entirely. ‘An old professor of mine said “If you put something over the side of ship, you can’t guarantee you get it back.”’

Will Whatley, the captain of the RRS Sir David Attenborough, likewise faces pressure in breaking through sea ice without sinking the ship to get to Rothera on schedule. ‘Sometimes we can’t get to somewhere because there’s too much ice and there’s lots of flights booked and plans in place – and we have to say “sorry”,’ Whatley admits. On another ship in 2017, he remembers heavy ice affecting the whole research season.

To help the RRS Sir David Attenborough get to Rothera on time, it has strain gauges in its hull, Whatley explains, ‘so we can see how close to the limits of strength the structure we’re getting to’. It’s designed to make break ice a metre thick at three knots. It can break thicker ice at slower speeds, but often he just pushes it gently along instead. ‘As ice gets older, the salt can leach out of it. It gets denser and much harder,’ Whatley says. ‘You hit it, then you back up and hit it again to try to make progress. Those are the tough times you would be getting towards the structural limits of the ship. We try to avoid it.’

This challenge is lessening as the climate heats up, but that’s not good news. ‘In December 2016, Antarctic sea ice declined abruptly, and over the following two years, Antarctica lost as much sea ice as the Arctic had lost in three decades,’ Ratnarajah says. By February 2023, sea ice reached a record low, over a third below the 1979 to 2022 average for the summer minimum, she adds. 2025 marked the third consecutive year of low sea ice extent. These rapid changes in sea ice are reshaping the Southern Ocean’s chemistry and biology ‘with major implications for global climate regulation and the resilience of polar environments’, Ratnarajah stresses.

Yet Antarctica’s unpredictability still threatens IronMan’s efforts to understand it better. ‘When you’re the chief scientist, you can’t leave the plan B, C, D, for when you’re at sea, so you’re preparing a lot,’ says Tagliabue.

‘You’re at the whim of Antarctica,’ Hendry agrees. ‘I need to get to the research station at the time that the ship gets to the research station. Making sure that those things align, it’s probably the thing I’m most nervous about. I’m going to be flying down to Antarctica, and either the ship or the plane could be delayed. There are always those concerns of Antarctic research – it’s much more challenging to get science done.’

Andy Extance is a science writer based in Exeter, UK

Article updated 10 December 2025 to correct mistakes around Stephanie Martin’s role and the design of the Kevlar-encased cables

1 Reader's comment