Our 2015 entrepreneur of the year is Ray Fisher of Peakdale Molecular

The 2015 Chemistry World entrepreneur of the year is Ray Fisher of Peakdale Molecular. Sarah Houlton talks to him about his career crafting molecules – and companies

Chemistry World entrepreneur of the year Ray Fisher has spent his career creating jobs for chemists. His route into chemistry followed the familiar pattern of a fascination with the bangs, smells and pops created by an excellent chemistry teacher at his Stourbridge grammar school in the UK. ‘He directed us to some good books that explained what chemistry is really about, especially when applied to civilisation, and what it can do – and has done – for people,’ Fisher says.

A chemistry degree at the University of Hull was followed by a PhD at the University of Manchester Institute of Science and Technology in organofluorine chemistry under the guidance of Robert Haszeldine and Tony Tipping. This sparked his interest in the industrial world – he describes them as both enthusiastic and commercially aware. ‘I had an enjoyable three years with them, but made the mistake of leaving Manchester before I’d finished writing up,’ he says. ‘I went home to Stourbridge, but my father’s new wife, a rather austere German lady, thought sitting around scribbling in a notebook all day was not appropriate and I should be out working, so I applied for, and got, the first job I saw, at Maybridge Chemical.’

His career making chemicals began with nine happy years in the Maybridge labs in Tintagel, Cornwall, where he also finished writing up. ‘We could make pretty much anything we liked, as long as it was commercially successful!’ he claims. ‘We’d make a material, and offer it for sale to anyone anywhere in the world. The idea was to make things they would be interested in buying.’

But Fisher became increasingly frustrated at the lack of investment in future development. It was a family-run enterprise, and he felt they were using it to fund their lifestyle, rather than as a forward-thinking business. ‘I saw a tremendous opportunity being wasted – I thought they could have done so much better had they developed the company with the aim of growing and becoming more influential, rather than taking all the money out of the business,’ he explains.

We never had a problem finding talented chemists

The owner, Roden Bridgewater, offered to sell the company to Fisher and two colleagues, Colin Deane and Tony Cooper, and they were some way down the line of raising the funds when Bridgewater changed his mind, having been persuaded by the family not to sell. But with the money-men already in place, Fisher, Deane and experienced businessman Richard Masterman decided to start a new company. The result was Key Organics, whose Camelford labs opened in Cornwall in 1986. Its business model was similar to that of Maybridge, but they were looking for a different customer set, and aiming to make higher quality products.

Northern exposure

After three or four years, his next challenge beckoned, as Fisher started to think Key was going the same way as Maybridge, with money being taken out of the business by his partners rather than re-invested to prime future growth. An attempt to acquire Fluorochem, back in the north west of England, fell through, but the experience left him determined to return north. And in 1992, in a small industrial unit 15 miles east of Manchester, Peakdale Molecular was born.

‘I divested myself of the past entirely, starting anew with the proceeds of selling my share of Key and a little help from Richard Masterman, but eventually I was on my own,’ Fisher says. Peakdale’s birth coincided with a tremendous demand for outsourcing in the pharmaceutical sector, particularly compounds for screening libraries. Fisher’s main business strategy was to sell custom-made intermediates that could be elaborated into library compounds, and it worked – by the end of the 1990s, they had outgrown their Glossop home.

In 1995 Fisher had met Christine Jones, a business studies graduate then employed as a training manager for chemical distributor Ellis and Everard. A year later, they married and she joined Peakdale, ultimately becoming operations director. To solve the space problem, the couple approached their bank manager, and the result was a custom-designed 40,000ft2 (3700m2) building – 20 times the size of the old facility – in Chapel-en-le-Frith, paid for on a mortgage-like basis. The building costs over-ran a little, but the funding gap was filled by venture capital investment from Close Brothers, now called Albion Ventures.

‘We devised a phased roll-out model for the building – duplicating what we had in Glossop in little profitable compartments of six or eight chemists,’ he says. ‘We started up in Chapel with 30 employees in 2001. But within a year there was a noticeable downturn in business post-9/11, with a lack of confidence in the biotech industry leading to the investment bubble popping. Big pharma was also beginning to experiment more with far eastern outsourcing, leaving us in a constant battle with procurement departments’ purchasing strategies, where lowest cost was more important than quality.’

Big pharmaceutical companies had invested in fantastic facilities and the best people in the belief that sales would continue to grow, Fisher says, but then procurement groups were incentivised to save money at the cost of quality, producing their own metrics designed to prove they were doing the right thing. ‘It’s like a Formula 1 team investing in the best drivers, cars and engineers, but then insisting on putting the cheapest, low-quality fuel in the cars, and wondering why they were no longer successful,’ he says. ‘It was a struggle, but we survived as we’d shown ourselves to be very capable chemists.’

As well as making intermediates for library makers, they run specific projects making individual compounds for testing, where the ability to design a complex synthetic route is essential. ‘We train our people to be responsive to customers’ requirements, and try to avoid a very hierarchical structure, encouraging chemists and customers to talk to each other,’ he says. And Chapel-en-le-Frith is a glorious place to be, with the Peak District on its doorstep. ‘We never had a problem finding talented chemists, with the lifestyle on offer.’

Branching out

Business perked up substantially with the rise of the FTE, or full-time equivalent, business model. Peakdale switched completely from custom synthesis and making screening compounds, which many companies do well, to this new system of renting out people and their skills. Success results from the talents and creativity of the chemists. ‘We took on more venture capital, from Kaye Enterprises and then Solon Ventures, to enable us to roll out the remainder of the building,’ he says. The business continued to grow, with the exception of a short period in 2009 when a few lay-offs were made – a move Fisher describes as over-defensive by the board. ‘I was subsequently proved right, but it was a tremendously unsettling time,’ he says.

A further expansion came in 2010, when they entered into an insourcing arrangement with Pfizer in Kent, with Peakdale initially employing 50 chemists on the Sandwich site. ‘At its maximum, this rose to about 80, and had Pfizer not exited the site I think it could have got even bigger,’ he says. Peakdale still has more than 30 chemists working in Sandwich, as a leading tenant on the new business park.

Peakdale now employs about 100 chemists across the two sites. Most are permanent full-time employees, but zero-hours contracts are also used, to the benefit of both company and chemist, Fisher explains. ‘It’s allowed us to employ people who have been made redundant by Pfizer or AstraZeneca but don’t want to move, and may have taken early retirement on redundancy,’ he says. ‘They don’t want to work full time, but would like to do some work and earn a bit of money on occasion when we need extra chemists. This flexibility enables us to expand our capabilities to meet temporary demand, without having to lay people off when that demand is no longer there. It’s been an absolute boon to us.’

Fisher is now in the process of leaving Peakdale, having sold it in July 2014 to Concept Life Sciences. Set up by a pair of former pharma industry executives with venture capital backing, Concept’s aim is to develop a conglomerate operating within the life sciences arena, via the acquisition of a range of companies with complementary skills. ‘I was delighted it wasn’t going to be taken over by a competitor who would take all the best bits out, close it down and get rid of the staff,’ he says. ‘We’d had a plan to do something similar ourselves – a build-and-buy programme to pick up smaller businesses and add the Peakdale way to them – but Concept came along with a similar plan, and it looked like a way for Peakdale to continue into a bigger and brighter future.’

About 80% of Peakdale’s business comes from the pharma/biotech sector, although over the years there has been some diversification into oil, cosmetics and even materials. And this search for different fields where Peakdale’s chemistry skills could be applied has led directly on to Fisher’s new venture – NeuDrive.

A new drive

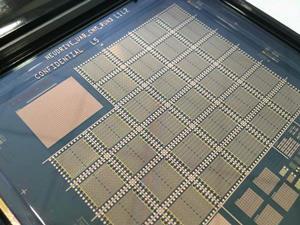

The technology that underpins NeuDrive came out of the UK government’s Northern Way initiative, a collaboration between the three northern regional development agencies (Yorkshire Forward, Northwest Development Agency and One NorthEast). Its aim, under the auspices of the Centre for Process Innovation (CPI), is to set up a supply chain for the printed electronics industry. Peakdale got involved in 2009 to supply specialist materials that make this technology possible.

‘Within a very short period of time, we had produced materials that had completely revolutionised performance,’ he says. ‘An additional layer of complexity was added because they have to be exceptionally pure, with just parts-per-million impurity levels. I was really excited by the project, and decided to buy this part of the business as part of the Peakdale sale.’

NeuDrive was set up with the intellectual property Peakdale had developed, and Fisher also acquired CPI’s IP late last year. ‘As a start-up business we’re now undertaking the battles of making ourselves known and finding customers to give us an income stream,’ he says. ‘It’s great fun. CPI put out a lovely press release saying we were a small company that took on a project that challenged the big players in the field, and smashed it. It just shows what a small company can do.’

The company’s technology platform allows them to produce high-performance, ultra-thin film organic transistors. Smartphones and screens have become thinner over the years, but they are set to get even more slimline. Transistors can now be printed onto flexible substrates, and then OLED (organic light-emitting diode) top planes added to give a high-definition screen that is almost as thin as a sheet of paper. It can even be rolled up without losing performance. ‘We’re creating alternatives to traditional electronics via organic materials that “talk” to each other,’ he says. ‘The list of potential applications is enormous.’

Rather than employing in-house lab-based chemists and technologists, NeuDrive is being run as a design house, instructing the manufacturers of materials, then application developers, and on to the prototype manufacturers of devices that can be made using the technology. These would then be sold on or licensed. ‘We have eight or nine people working for us in labs at the moment,’ he says. ‘We may even become a significant customer of Peakdale in the future.’

Sweeping changes

Although he no longer directly employs lab-based chemists, Fisher remains incredibly proud of the career opportunities his past and present businesses have provided to the chemistry community. ‘It’s great that we’ve been able to provide jobs and see people progress in their own careers,’ he says. ‘And many people have been given the chance to see the way commerce works, and go out and benefit from it.’

Chemistry will be at the heart of making it happen

And he believes his past experience of the pharma business, with its well-developed outsourcing model, will be of real benefit to the printed electronics world as it grows and matures. ‘I’m introducing new thinking to the team, and through the contacts I already have and the new ones I’m making I can see overlaps that hadn’t been thought of in traditional pharma,’ he says. ‘It’s great to live life at a more leisurely pace and do things I didn’t have time for in the past, but I still have the lovely excitement of being at the cutting edge of a technology that will be so important in the future.’

Fisher is greatly excited by the technology’s potential. ‘It will completely revolutionise the way industrialised nations operate,’ he sys. ‘As the 20th century saw a sweeping change from carts to cars to aeroplanes, this is going to be responsible for a huge change in this century.’

And the potential stretches a long way past ultra-thin display screens. Prosthetic limbs have come on tremendously in recent years, but how could a prosthetic hand, say, be made to behave like a real hand? ‘The hand has to communicate both ways – it has to operate mechanically, but would also have to feed back to the body information about what it is touching,’ Fisher says. ‘What if the materials themselves can act as sensors, and provide that feedback? Once that happens, the human brain might be able to take over anything. It could plug into a car and feel the tyres and engine. That’s just one idea, and it remains very blue sky and I doubt we will see it in my lifetime, but as long as it’s pursued it will happen, for sure. And chemistry will be at the heart of making it happen.’

Sarah Houlton is a science writer based in Boston, US

No comments yet