The discovery of catalytic RNA transformed our understanding of life’s beginnings. Clare Sansom explores how the RNA world hypothesis bridges the gap between non-living chemistry and the first cells

- The RNA world hypothesis proposes that early life relied on RNA alone to store genetic information and catalyse chemical reactions, resolving the apparent chicken‑and‑egg problem posed by the modern DNA–RNA–protein system.

- The discovery that the ribosome is a ribozyme, along with the versatility of RNA, provides strong evidence that RNA pre‑dated both DNA and proteins in the evolution of life.

- Recent work in prebiotic chemistry suggests that many of life’s essential building blocks could have arisen together from simple molecules such as hydrogen cyanide, enabling the emergence of RNA‑based protocells without stepwise assembly.

- Although the RNA world hypothesis cannot be proven and may not tell the whole story, it remains central to theories of abiogenesis on Earth and informs the search for life, including possible RNA‑based systems, beyond our planet.

This summary was generated by AI and checked by a human editor

Imagine boarding a time machine that takes you back through the whole history of life on Earth. You would rapidly travel through the thin sliver of time that covers human history and pre-history; reach the age of the dinosaurs within a few hundred million years, and then see animal life crawl back into the oceans. Those ancient seas were still teeming with life, but you would soon observe the reversal of the Cambrian explosion that gave rise to invertebrates like ammonites and trilobites. You would then pass through perhaps a couple of billion years of primitive, mainly single-celled, life.

Somewhere in the darkness you would pass the primitive microbe known as Luca, or the last universal common ancestor of eukaryotes, bacteria and archaea. We know almost nothing about what Luca would have looked like or even when it appeared: it might have been 3.5 billion years ago or up to 800 million years before.

At the very far end of the timeline, we know that Earth was formed about 4.5 billion years ago, and that during the next 100 million years it cooled sufficiently for liquid water, one of the main prerequisites for life, to exist on its surface. From this point, the early Earth could be classed as habitable: that is, its temperature and pressure were such that some form of life could, potentially, form.

The central dogma’s dilemma

The unknowingly huge gap of time between the first liquid water and the emergence of Luca will have been filled by abiogenesis, or the process through which life originated. This occurred during the Hadean or early Archean eon, the first two of four geological eons of our planet’s history as defined in earth science. The earliest life forms have left no traces behind, so we can know very little of how the complex and long-drawn-out process of abiogenesis occurred. We do know, however, that it took place on a planet that was very inhospitable to life as we know it today, with no atmospheric oxygen.

But how, exactly, should life be defined? Perhaps surprisingly, this is not a straightforward question to answer. One definition, coined by Nasa, states that ‘Life is a self-sustaining chemical system capable of Darwinian evolution’ and further describes it as ‘chemical in essence’.

Scientists have been fascinated by, and have speculated on, the origin of life since well before Darwin’s theories became widely accepted. It seems obvious that the process must have started with a mixture of abiotic but increasingly complex chemicals and ended with ‘protocells’ that evolved into cells as we know them, with chemical components capable of replication (DNA), metabolism (proteins) and compartmentalisation (lipids). The ordered steps in between, and the nature of the first molecules that were able to self-replicate, self-assemble, catalyse chemical reactions and form membranes, are still partly mysterious.

Once the basic principles of the deceptively simple central dogma of molecular biology had been discovered, some of the greatest minds in molecular biology became captivated by what appeared to be a classic chicken and egg dilemma: it was difficult to imagine how any of the steps ‘from DNA to RNA to protein’ could arise independently, so which came first?

The ribosome is a ribozyme

Francis Crick and his long-time colleague Leslie Orgel started from the big picture. ‘How could life get started … it would need an informational molecule, and a catalytic molecule [to arise simultaneously] … All of this would be solved if only RNA could be catalytic … which seems unlikely,’ mused Orgel. The microbiologist Carl Woese, who held a chair at the University of Illinois Urbana–Champaign in the US, is best known for defining the Archaea as the third domain of life. He paired up with Harry Noller of the University of California Santa Cruz and started by focusing on RNA. ‘Woese and Noller were captivated by the ribosome … they became convinced that RNA was its catalytic heart … but at that time no-one had observed RNA catalysis,’ explains Thomas Cech of the University of Colorado, US.

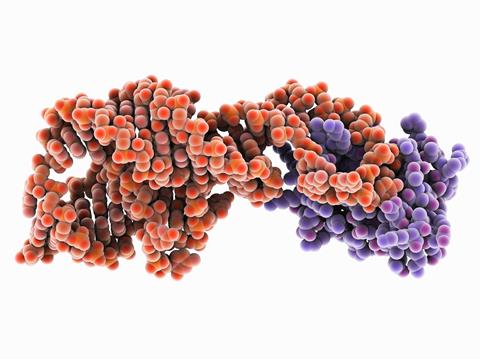

In the early 1980s, Cech became the first to observe and recognise catalytic RNA and to coin the name ‘ribozyme’; he shared the 1989 chemistry Nobel prize with Sidney Altman of Yale University in Connecticut, US, for their independent discoveries. And once the first low-resolution ribosome structures had been solved it became clear that Woese and Noller’s original hunch was also correct. The ribosomal catalytic site was, indeed, composed entirely of RNA, with the proteins acting as a scaffold. The ribosome is a ribozyme.

The discovery of ribozymes underlined the unique versatility of RNA. It can self-replicate and store information like DNA, but it can also catalyse chemical reactions, like proteins. It therefore seems very likely that ribozymes will have preceded proteins as the catalytic machinery of protocells. Many researchers believe that the gap in time between complex but non-living mixtures of chemicals on the early Earth and Luca will have been partly filled by simple RNA-based life-forms, with no DNA or proteins: life before the central dogma, then, would have been an RNA world. ‘Suddenly there would have been an RNA that was able to catalyse quite sophisticated chemistry with incredible accuracy and a trillion-fold acceleration over the [non-catalysed] chemical rate,’ proposes Cech. Nevertheless, he stresses that the historical accuracy of this can perhaps never be proven. ‘The transition from non-life to life has not been observed experimentally.’

We know that ribosomes go back through evolutionary history to even before Luca

The idea that RNA would have preceded DNA rather than the other way round can, however, be inferred from its basic biochemistry. While the synthesis of RNA requires a complex series of metabolic reactions, the chemical process of converting RNA into DNA is remarkably simple. It requires only two reactions: reducing the ribose sugar by deoxygenation at the 2’ position and methylating the pyrimidine base uracil at the 5-position to give thymine. Biochemically at least, DNA could almost be described as an afterthought.

The nature and functionality of the ribosome give further clues about the pre-eminence of RNA in the story of life’s origins. ‘As the molecular machines that catalyse protein synthesis, these ribozymes carry out one of the most important reactions in the cell,’ explains David Lilley of the University of Dundee in the UK. ‘Furthermore, we know that ribosomes go back through evolutionary history to even before Luca … this “molecular fossil” in our cells is a further bit of evidence for life evolving from a stage when RNA did all the catalysis.’

From primordial soup to protocells

But what could that RNA world have looked like, how could it have arisen from what some commentators term the primordial soup of pre-living chemicals, and how could it have transitioned into the molecular biology we see today? Cech has suggested that ‘the fun comes when we try to use our secure knowledge of the modern RNA world to infer what the primordial RNA world might have looked like’. This ‘secure knowledge’ of RNA has recently given us the vaccines that brought us through the height of the Covid pandemic, so what can it tell us about the more abstruse but no less fascinating questions of the origin of life?

A complete RNA world theory would need to include three essentially consecutive stages of evolution: from the synthesis of the molecular precursors to information carriers, catalysts and membranes, through a stage where RNA acted as both catalyst and information carrier, to the assembly of protocells. Even the simplest forms of life – that ‘self-sustaining molecular system capable of Darwinian evolution’ – requires chemical complexity, but you can’t put a number on how complex it would have to have been.

John Sutherland of the MRC Laboratory of Molecular Biology in Cambridge, UK, an expert on prebiotic organic synthesis, explains this memorably using, of all things, a quote from a Monty Python sketch. ‘The sketch names “Elk theory” as the trite observation that “All brontosauruses are thin at one end, thicker in the middle, and then thin again at the far end” – but not everything with these dimensions is a brontosaurus! Similarly, life demands a level of chemical complexity, say N, but not every chemical mixture with this complexity will have the qualities of life,’ he explains. ‘And we can’t expect the chemistry of very early life to be more than roughly equivalent to metabolism as we understand it today.’

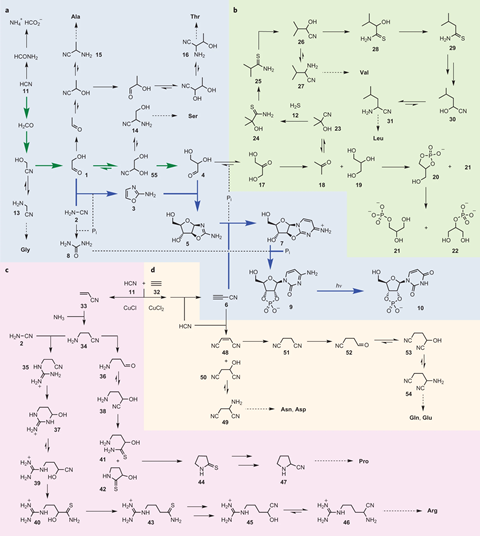

Until recently, it has been assumed that the informational, metabolic and compartment-forming systems necessary for protocells must have appeared consecutively. However, Sutherland and his co-workers are now suggesting an ‘essentially plausible scenario’ in which a necessary set of biomolecular building blocks could have been produced all at once from the same chemistry. Perhaps counter-intuitively, this would have started from a simple toxic compound: hydrogen cyanide (HCN).

The process that could have produced an astonishingly rich chemistry from such a simple molecule is known as reductive homologation. Essentially, this involves converting an organic compound into the next member of its homologous series by adding one unit at a time, so that, for example, the first stages of the reductive homologation of methanol give ethanol, propanol and butanol. ‘In fact, nearly half the proteogenic amino acids of modern biochemistry, plus nucleosides and lipid precursors, can be derived from HCN and some of its basic derivatives using this chemistry,’ explains Sutherland. ‘Furthermore, the carbon and nitrogen in HCN are at close to the ideal biological oxidation level.’

Evolution without catalysis

This idea poses a further question, however: where did the hydrogen cyanide come from? It can be made photochemically with ultraviolet light in a reducing atmosphere, but these conditions were rare on the early Earth. ‘Meteorite bombardment would have produced transient reducing conditions that could lead to the cyanide-based starting materials for life,’ explains Jack Szostak of the University of Chicago in the US. ‘Ultraviolet radiation would have been plentiful, as there was very little oxygen or ozone in the atmosphere to block it.’

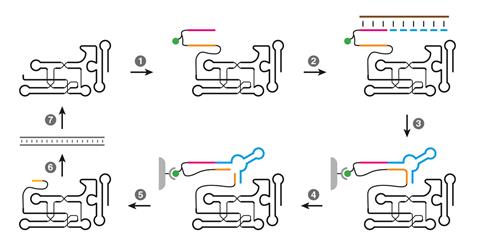

RNA must have evolved from its precursor molecules at the start of a process covering many millions of years. ‘Initially, Darwinian evolution could have taken place on a molecular level without macromolecular catalysis, just using chemistry and physics to drive RNA replication,’ adds Szostak. This replication would have occurred by synthesising a complementary strand on an RNA template and then synthesising a copy of the original strand on that one. The process would have been error-prone, and those sequence variants that replicated effectively would have come to dominate the mixture in a process resembling Darwinian evolution.

It is thought that this process could eventually have led to RNA evolving into a ribozyme that acted as its own polymerase, and that this RNA-directed RNA polymerase could generate larger RNA molecules with more complex functions. Although we know of no natural ribozymes with this type of polymerase activity, they have been synthesised in the laboratory using directed evolution methods in which large pools of random RNA sequences are generated and probed for sequences with a required function. ‘As the copying fidelity of artificial RNA polymerases increases, this “test tube evolution” will reliably generate longer RNA sequences with more complex functions,’ explains David Horning of the Salk Institute in California, US. Recent experiments by his team demonstrated that an artificial polymerase could evolve new variants of the hammerhead ribozyme, a compact polymer of approximately 34 base pairs with exquisitely precise self-cleaving activity. ‘We can imagine that, over millions of years, a form of RNA-only evolution could generate increasingly complex ribozymes,’ adds Horning.

This might even have led to a ribozyme that could catalyse an early form of protein synthesis, with a limited genetic code, tRNA and amino acid repertoire: an RNA-only proto-ribosome. Interestingly, a mechanism of this type was proposed as far back as 1976 in a paper by Crick, Sydney Brenner and others entitled ‘A speculation on the origin of protein synthesis’. The mechanism suggested would have imposed limitations on the base sequence and the proto-genetic code such that only four amino acids could have been synthesised: glycine, serine, aspartic acid and asparagine.

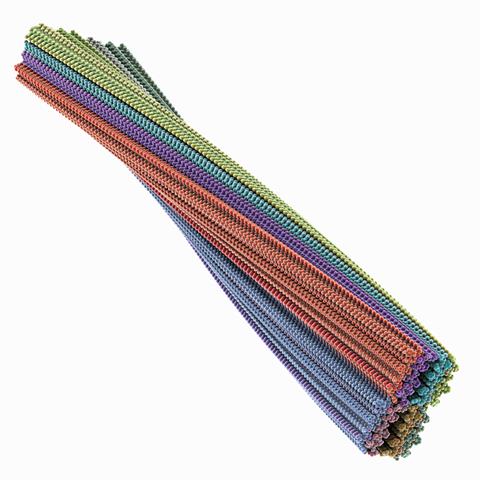

The RNA world hypothesis is an important and widely understood one, but it can never be proven. As it is, it still poses many questions about the origin of self-replicating RNA and its stability and functionality under early Earth conditions. Some scientists therefore propose that RNA may not have been the first self-replicating polymer after all. Peter Maury of the University of Helsinki in Finland is one of those who has suggested that self-replicating amyloid fibrils might have co-existed with, and formed a stabilising scaffold for, RNA. ‘We know that certain amino acids can be synthesised and polymerise into short peptides in harsh conditions like those on the early Earth,’ explains Maury. ‘And under the same conditions they can assemble into amyloid fibrils without enzyme catalysis.’ Furthermore, amyloid can form different polymorphs and the most stable, or fittest, of these will naturally expand over time. Amyloid, therefore, could have been the first self-assembling system, evolving without a genetic code and pre-dating and providing stability for an RNA-based system.

It is important to realise that these theories are not necessarily completely incompatible. Both propose that RNA pre-dated DNA as the main informational molecule by perhaps hundreds of millions of years, and both envisage a complex system comprising many different molecules. The main difference is in the nature of the first self-replicating molecule, and this must remain speculation; there are no molecular fossils that can be discovered.

Life beyond Earth?

Perhaps we can learn more by looking beyond the Earth for abiogenesis, with deep space replacing deep time. But how might the presence of extraterrestrial life be observed? Andrew Rushby studies the conditions necessary for habitability in the solar system and beyond at the Centre for Planetary Science at University College and Birkbeck College, London. ‘We use spectroscopy to look for biosignatures: molecules in planetary atmospheres that can only be, or are very likely to be, synthesised by biological systems,’ he explains. ‘But we need to be patient and look at other possibilities first, before jumping to conclusions; our first golden rule is “It’s probably not life!”’ Oxygen in an atmosphere, for example, is very likely but not inevitably a product of biosynthesis, so other evidence would be necessary before it can be accepted as a biosignature.

I am confident that there are no advanced civilisations within about 100 light years

Lilley has speculated that, as it is energetically cheaper to make RNA than proteins, it might be productive to look for modern organisms with RNA-catalysed chemistries in ‘very energy-reduced environments … such as in micro-organisms that have lived at the bottom of Lake Vostok [in Antarctica] for millions of years, or even floating under the ice of Saturn’s moon, Enceladus.’ It is not impossible that an RNA-based world, or, indeed, an amyloid one, might be found under the surface of Enceladus or another gas-giant satellite within our solar system.

But could life be found outside the solar system, if it is one day possible to look there? We have no evidence either way. As far as we can tell, life would only be possible in an environment with temperatures that support liquid water, on a planet or moon with a size and composition that gives it a gravity fairly similar to ours. ‘I personally am confident that there are no advanced civilisations within, say, about 100 light years of our Solar System,’ says Rushby. ‘Primitive life is another matter, however; we might find that the Universe is full of bacteria.’ Or perhaps we might find further RNA (or amyloid) worlds out there.

We can think of investigating the origins of life, on Earth or elsewhere, as like solving a multi-dimensional jigsaw puzzle. We have many more of the pieces than the mid-20th century molecular biology pioneers did, but the picture is still nowhere near complete. But there is one thing that we can be (almost) certain of: the pre-eminence of the versatile RNA, the central dogma’s molecule in the middle.

Clare Sansom is a science writer based in Cambridge, UK

1 Reader's comment