Scientists are using non-thermal plasma to produce fertiliser and long-chain hydrocarbons. Mason Wakley talks to the chemists harnessing the fourth state of matter

- Scientists are increasingly turning to non‑thermal plasma as a low-energy way to drive chemical reactions, offering an electrified alternative to traditional high‑temperature, high‑pressure processes.

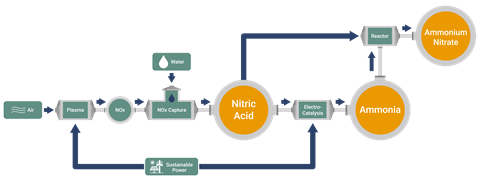

- UK spin-out Plasma2X is using cold plasma to convert air and water into nitric acid and ammonia, aiming to cut emissions and costs compared with the Haber–Bosch process.

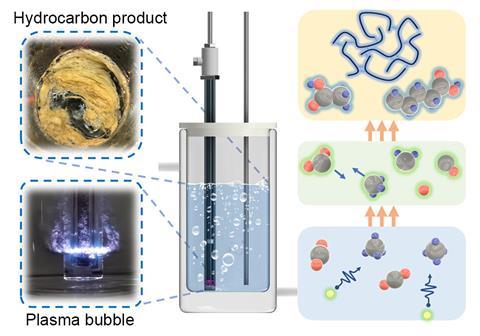

- Researchers are also using plasma to upgrade gases such as methane and carbon dioxide, with recent work showing that biogas can be transformed into long‑chain hydrocarbons using cold plasma.

- Beyond synthesis, plasma technologies are being deployed commercially to prime seeds for faster germination and higher yields, though scaling remains a challenge for both chemical and agricultural applications.

Article summary generated by AI and checked by a human editor

In the early 20th century, the Haber–Bosch process – which creates ammonia from hydrogen and nitrogen – revolutionised the world. About a decade earlier, in 1903, Kristian Birkeland and Samuel Eyde were instead trying to fix atmospheric nitrogen using plasma. Passing air through two highly charged copper electrodes and a strong magnetic field to create a plasma allowed the Norwegian chemists to eventually produce nitric acid. Unfortunately, the efficiency of their process couldn’t compete with Haber–Bosch and it has largely been forgotten.

As the world continues to move away from fossil fuels, scientists are looking for ways to harness the power of electricity for chemical applications. Using plasma – like Birkeland and Eyde – offers one way to do so. Sometimes named the fourth state of matter, plasma is a curious collection of ions, reactive species, electrons and neutral atoms. Plasma can conduct electricity and is influenced by both electric and magnetic fields. Irving Langmuir first named this state in the 1920s, as it reminded him of the analogous ‘way blood plasma carries red and white corpuscles and germs’.

It is estimated that nearly 99.9% of all observable matter in the Universe is made of plasma. Stars are large, condensed balls of plasma, while the plasma making up the interstellar medium is much less dense. Such matter is rarely seen on Earth, except in the form of the beautiful aurorae in the upper atmosphere, lightning, certain high-temperature flames and neon signs. Until recently, television screens also made use of plasma technology, though this has now been superseded by more efficient liquid crystals and organic light–emitting diodes.

How to make plasma

To create a plasma, there needs to be a source of energy to pull electrons from gaseous atoms. In places such as stars, the high temperatures and pressures cause atoms to collide vigorously and they subsequently break apart. In space and the upper atmosphere, high energy photons excite electrons in atoms and molecules, frequently leading to complete deionisation.

Elsewhere, the most common way of creating a plasma is by using an electrical discharge, in a similar vein to Birkeland and Eyde in the early 1900s. ‘A gas is passed through two or more electrodes of high voltage, which causes the gas to break down and creates a mixture of electrons and reactive species,’ says Xin Tu, an expert in plasma chemistry at the University of Liverpool in the UK.

In cold plasmas, most of the energy is used to create reactive species and electrons

He explains that different types of plasma can be created, depending on the voltage and frequency, technique, and whether an alternating or direct current is used. Using high energy sources such as microwaves creates what is known as a thermal plasma, one in which all species – including electrons, ions and atoms – are at the same temperature. Such plasmas can reach over 10,000°C in temperature.

In contrast, non-thermal or cold plasmas are much nearer to ambient conditions, as ‘most of the energy is used to create reactive species and electrons, rather than heating the gas’, explains Tu. Dielectric barrier discharge – where electrical discharge occurs between two electrodes separated by an insulating dielectric material – is a common way of producing such plasmas. An alternative method is corona discharge, as seen in the novelty plasma balls of the 1980s, where an electrical current passed through a conductor – such as a wire – generates a strong enough surrounding electric field to ionise the gas molecules.

Plasma for ammonia

In recent years, scientists have been using non-thermal plasmas to synthesise a variety of commodity chemicals. ‘By using non-thermal plasma for a chemical process, it means that you can significantly cut costs or even reduce the number of chemical steps,’ explains Tu. He adds that such plasmas do not require as much energy input compared to thermal plasma, as only the electrons are excited.

In 2023, Tu started Plasma2X with co-founder Mike Craven. Their UK-based spin-out focuses on using non-thermal plasma to generate nitric acid and ammonia from air and water. ‘The energetic electrons [in the plasma] activate the nitrogen and oxygen bonds, which opens up a pathway known as the Zel’dovich mechanism,’ Craven says, explaining that this is the most energy efficient pathway known to produce nitrogen oxides. This gas is then fed through water to create nitric acid, of which Plasma2X can currently produce several kilograms per day. Nitric acid can then be electrochemically catalysed to form ammonia. Combining both of these reagents together forms ammonium nitrate, one of the most common fertilisers globally.

The Haber–Bosch process – the typical method to synthesise ammonia – generates over 200 million tonnes of ammonia each year. Yet it is an expensive and highly energy intensive process, accounting for around 2% of the world’s yearly energy consumption. Plasma2X are hoping to cut emissions and costs by harnessing electricity generated from renewable energy. Craven explains that while renewable energy sources are often intermittent, the design of the system allows modules of reactors to be turned on and off as needed. This helps keep reactions operating at full efficiency.

Making hydrocarbons

Generating plasma is still a relatively energy intensive process, but certain reactions may benefit from using plasma, such as those that typically use large amounts of energy, either to create high temperatures or pressures. Patrick Cullen, a plasma chemist at the University of Sydney in Australia, explains that plasma is a platform technology. ‘If you can split nitrogen, you can also split oxygen or carbon dioxide [as] you’re using the plasma to do the heavy lifting,’ he says. Cullen is the founder of PlasmaLeap, one of the many other businesses also trying to commercialise the conversion of nitrogen in the air into ammonia.

As for his own research, he is also looking at using plasma to unlock reactions involving carbon-based gases and oxygen. In 2024, Cullen and his research group showed how they were able to use cold plasma to convert biogas – a mixture of methane and carbon dioxide – into long-chain hydrocarbons, reaching up to chain lengths of 40 carbon atoms. The researchers bubbled the biogas through water, before exposing the reactants to plasma discharges. By varying the ratio of methane to carbon dioxide fed into the reaction vessel, Cullen and his team were able to increase the selectivity of the specific hydrocarbon that formed. Cullen explains that ‘this [bubbling method] is beneficial because it helps control the diffusion and reactivity of species’.

‘[However], one of the problems with plasma is sometimes it’s not [always] that selective,’ explains Cullen. ‘Plasma often produces a cocktail of reactive species of widely different timescales and chemistry.’ To overcome this issue, he describes how there is growing tendency to couple plasma reactors with electrochemical systems and catalysts, to ‘target more complex chemistry or increase selectivity’. The ability to quickly turn on and off reactors – aside from the benefits of using intermittent energy sources – aids selectivity, particularly as some products equilibrate back to starting materials if left over long times in activated conditions.

Another challenge currently facing plasma technology is the scale of plasma generation. ‘As you scale up, you lose energy efficiency with these non-thermal plasmas – you don’t have that problem with classic chemistry of temperature and pressure,’ says Cullen. Expanding the electrode area destabilises the formation of plasma, so the surface area of the electrode needs to increase with the overall reaction volume.

Growing applications

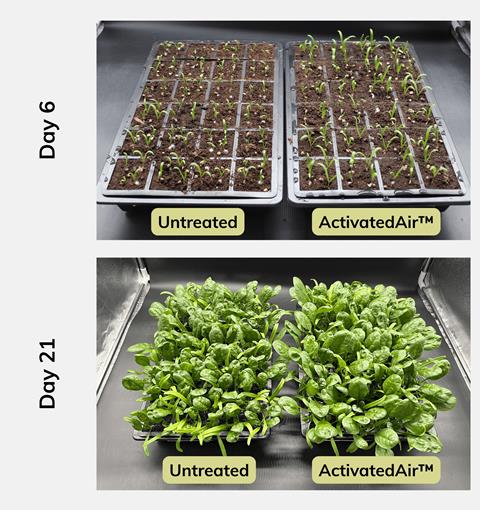

Away from synthetic chemistry, plasma has applications in many other areas. Several research groups have been looking at how to boost the efficiency of agricultural production by priming seeds with plasma before sowing. This method can help boost yields, shorten growth periods and subsequently increase the number of crop cycles per season. Zayndu – a company spun out of Loughborough University, UK – has developed the technology so that it is now viable on a commercial scale.

‘When air is converted into plasma, it generates reactive oxygen and nitrogen species which kick-start several biological processes in seeds,’ says Alberto Campanaro, head of research and development at Zayndu. He explains that one of the main benefits of such reactive species is the resulting increase in a seed’s permeability, owing to both physical etching and chemical modification of the seed coat. Both of these improve water uptake by the seed. Plasma can also reduce the number of seed-borne pathogens, lowering the risks of diseases that primarily affect seedlings.

Campanaro also explains that the main benefit of reactive oxygen species is that they trigger hormonal responses. Seeds produce abscisic acid, a hormone involved in inducing and keeping seeds’ dormancy, which prevents their germination even under favourable conditions. Another hormone – gibberellic acid – kicks in to promote seed germination when the time is right. Reactive oxygen and nitrogen species in the plasma can influence the hormone balance in the seed, enabling control over the germination process. ‘As soon as the seed receives humidity, some of the [chemical] processes are already done, so germination is just much faster,’ says Campanaro.

In one trial conducted by Zayndu, spinach plants that had their seeds pretreated with plasma had an increase of 18% plant weight at harvest, compared to the untreated equivalent. ‘Even a much more modest 5% increase can make significant financial gains for growers,’ he says.

‘What we’ve done is take a technology that was [initially] done on five, 10, 20 seeds at a time, and we developed equipment that can do kilograms of seeds in a go, day in and day out,’ says Campanaro. ‘We have two sizes of machine – one can do a kilo of seeds every few hours, the other, three to four kilos in the same time span.’

‘The majority of our customers are greenhouse vertical farmers,’ he says, adding that broadacre farms would require priming tens of tonnes of seeds per day in a very short period of time, which is currently unachievable with Zayndu’s existing technology, but still a target for them.

‘From leafy greens and salads to ornamental flowers and tree seeds for afforestation, there are many species that this technology can work on,’ says Campanaro, adding that around 100 species and 200 varieties of plants have been tested with to date. He also notes, however, that ’the process needs to be fine-tuned for each species, as not every species responds in the same way’.

A low energy plasma future

Like the variability among plant species, not every type of process will benefit from using plasma. Of course, plasma is largely limited to reactions where at least one of the reactants can be made gaseous. Certain chemical transformations – such as converting methane into hydrogen – still currently rely on high-temperature thermal plasmas, with further work needed to operate the reaction at ambient conditions. Jonathan Harding, who works at Plasma2X, adds that ‘there’s also the balance of not just picking the right reaction [to use plasma] but in matching the reactor with the type of plasma you’re using’, which adds another level of complexity to plasma chemistry.

Outside of chemical transformations, plasma is at the heart of efforts to fuse light elements together, by recreating conditions found within stars on Earth, as this potentially offers an untapped, renewable energy source. Sterilising water sources or treating bacterial infections using reactive oxygen species generated within plasma are another application. Non-thermal plasma devices are also increasingly entering the market as an alleged non-invasive way to promote skin rejuvenation.

From the early plasma chemistry of Birkeland and Eyde, the efficiency of plasma has greatly improved, opening up countless applications. Plasma’s use in society going forwards will likely only grow, particularly in the chemical industry, which Craven says is ‘one of the last big electrification challenges’.

Mason Wakley is a science correspondent for Chemistry World

No comments yet