Albert Hofmann has largely faded from public view but his creation has become part of our cultural fabric. David Nichols reports

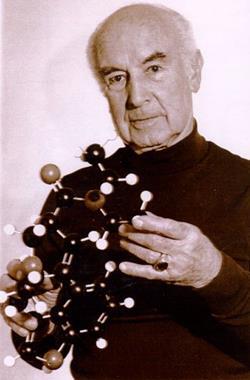

Albert Hofmann, who discovered LSD (d-lysergic acid diethylamide), is soon to celebrate his 100th birthday with his wife Anita, their children, grandchildren, and great-grandchildren.

Sitting in the quiet back yard of his little home in Switzerland, overlooking the long green hill that swoops down to the Alsace region of France, this gentle and unassuming man is anything but the stereotype of a world famous chemist. He brings out a bottle of home-made Kirsch, made from cherries grown on his own trees. He smiles as he pours a small glass to sample, and as I slowly sip he tells me about his life. The years have taken their toll on his now fragile body, but his mind is alert and his intellect intact.

He is warm and effusive. His love for nature and beauty is overwhelming. He is also a very spiritual man, and has a strong belief in God.

I ask him when he began to think of spiritual things. He talks about the time he was a child walking through the garden one May morning, that he remembers as vividly as if it were yesterday. As he was walking, he had an overpowering visionary experience, where suddenly everything shone with brilliant radiance and majesty. He stood spellbound. Afterwards he was filled with joy, but had no words to describe what he had seen and felt.

He had several more such deeply euphoric moments as a child on his walks through nature. These experiences shaped the main outlines of his world view and convinced him of the existence of a miraculous, powerful, unfathomable reality that was hidden from everyday sight.

He glosses over the details of much of his younger life, but notes that the decision to become a chemist was not easy. He had already taken a Latin matricular exam, and seemed headed toward a career in the humanities, although he was tempted to become an artist. Ultimately, he was more attracted by the theoretical foundations of chemistry, and to the surprise of his family and friends made the decision to study chemistry.

He pauses only briefly to comment on his doctoral studies at the University of Zurich, when he determined what lobster shells and insect skins are made of, a material now known as chitin. Yet, even as a novice chemist he was so accomplished that he finished the experiments for his doctoral degree in only a few months. He was now ’Dr Albert Hofmann’ in 1929, at the tender age of 23.

Chemistry and botany

The Swiss pharmaceutical industry was Hofmann’s next stop and home for the rest of his professional life. He began work as a natural products chemist at the pharmaceutical giant Sandoz, in Basel. He worked with Arthur Stoll, who directed a programme isolating and purifying the active principles in medicinal plants. The combination of chemistry and botany was particularly fascinating for Hofmann. After cutting his teeth on several projects focused on cardiovascular products, he began work on the ergot alkaloids. These powerful substances are produced by the ergot fungus that infects grain. They had not been extensively explored, and were a natural product chemist’s nightmare. They were complex, chemically unstable, and could rapidly decompose into useless black tars if not properly handled.

Ergot extracts had been used for hundreds of years by midwives to prevent death from excessive bleeding that often followed childbirth. Ergotamine, an alkaloid first purified from ergot in 1918 by Stoll, was used to treat postpartum bleeding, and migraine headache.

Medicines derived from ergot alkaloids were a significant market for Sandoz. Hofmann became a world expert on the chemistry of ergot alkaloids and he discovered a number of therapeutic agents that provided significant revenues for Sandoz. It was during this work that Hofmann’s journey took a side road.

Ergot-derived compounds are also extremely potent, with only very small dosages are required for a therapeutic effect. Hofmann realised that many new types of drugs, if built upon the basic ergot alkaloid chemical framework, might have exceptional potency as therapeutic agents.

Exploring lysergic acid

The essential molecular core for most of the ergot alkaloids is lysergic acid. Under the proper chemical conditions ergot alkaloids could be fragmented into lysergic acid plus other by-products. This lysergic acid could then be isolated and recombined with different chemical building blocks to create a variety of new ergot derivatives that did not occur in nature.

Hofmann began to explore ways to couple lysergic acid with other organic molecules to create potential therapeutic agents. It is unclear how many of these lysergic acid amides he ultimately created. He developed the Sandoz products dihydroergotamine, hydergine, and methergine, drugs used to treat migraine, circulatory disorders, and postpartum bleeding, respectively.

He created the 25th molecule in the series, LSD-25, by combining lysergic acid with a diethylamine building block.

The choice of building blocks for this particular molecule was not entirely random. Hofmann recalls: ’It is remarkable how clearly I remember the circumstances under which the idea of synthesising the substance lysergic acid diethylamide came to me. I was pacing back and forth, ruminating on my work. Suddenly there occurred to me the well-known circulatory stimulant Coramine, and the idea and possibility of synthesising an analogous compound based on lysergic acid, which is the basic building block of ergot alkaloids. Chemically, Coramine is nicotinic acid diethylamide, and I analogously planned to synthesise lysergic acid diethylamide. The chemical-structural similarity of these two compounds led me to expect analogous pharmacological properties. With lysergic acid diethylamide I hoped to obtain a novel, improved circulatory stimulant.’

LSD-25 was synthesised in November 1938. Pharmacological assessment revealed nothing of interest and further investigation of LSD was abandoned. The story might have ended there. But it didn’t. Five years later, in the spring of 1943, Hofmann synthesised another sample for further pharmacological testing, operating on no more than a hunch. He says that he ’liked the chemical structure of the substance’, which apparently was enough to motivate him to prepare a new sample. Hofmann himself cannot say why he had this hunch that the pharmacologists had overlooked something with this particular compound.

On Friday 16 April 1943, in the course of recrystallising a few hundredths of a gram of LSD for analysis, Hofmann reports that he ’was seized by a peculiar sensation of vertigo and restlessness. Objects as well as the shape of my associates in the laboratory appeared to undergo optical changes. I was unable to concentrate on my work. In a dreamlike state, I left for home, where an irresistible urge to lie down and sleep overcame me. Light was so intense as to be unpleasant. I drew the curtains and immediately fell into a peculiar state of ’drunkenness’, characterised by an exaggerated imagination. With my eyes closed, fantastic pictures of extraordinary plasticity and intensive colour seemed to surge towards me. After two hours, this state gradually subsided and I was able to eat dinner with a good appetite.’

As he reflected on the experience, and what might have caused it, he concluded that it must have been an accidental exposure to the LSD-25 he had been preparing.

He resolved to carry out an experiment on himself with LSD-25 to determine whether it had been responsible. He took what he believed to be a miniscule amount, one-fourth of a milligram. Forty minutes later and after he wrote less than 50 words in his observation log, he stopped writing because, ’the last words could only be written with great difficulty’.

A bicycle ride

The rest of his story is now a classic. ’I asked my laboratory assistant to accompany me home as I believed that my condition would be a repetition of the disturbance of the previous Friday. While we were still cycling home, however, it became clear that the symptoms were much stronger than the first time. I had great difficulty in speaking coherently, my field of vision swayed before me, and objects appeared distorted like the images in curved mirrors. I had the impression of being unable to move from the spot, although my assistant told me afterwards that we had cycled at a good pace.’

Hofmann was convinced that he had poisoned himself, even with the extremely small quantity he had ingested. ’The faces of those present appeared like grotesque coloured masks; strong agitation alternating with paresis; the head, body and extremities sometimes cold and numb; a metallic taste on the tongue; throat dry and shrivelled; a feeling of suffocation; confusion alternating with a clear appreciation of the situation. I lost all control of time: space and time became more and more disorganised and I was overcome with fears that I was going crazy. The worst part of it was that I was clearly aware of my condition though I was incapable of stopping it. Occasionally I felt as being outside my body. I thought I had died. My ’ego’ was suspended somewhere in space and I saw my body lying dead on the sofa. I observed and registered clearly that my ’alter ego’ was moving around the room, moaning.’

Overwhelming images

A doctor arrived at the height of the intoxication, but found nothing life-threatening, only dilated pupils and a somewhat weakened pulse. Six hours after he began his experiment with LSD, Hofmann’s condition was definitely improving, although ’the perceptual distortions were still present. Everything seemed to undulate and their proportions were distorted like the reflections on a choppy water surface. Everything was changing with unpleasant, predominantly poisonous green and blue colour tones. With closed eyes multihued, metamorphosising fantastic images overwhelmed me. Especially noteworthy was the fact that sounds were transposed into visual sensations so that from every tone or noise a comparable coloured picture was evoked, changing in form and colour kaleidoscopically.’

In the morning he felt relieved and rejuvenated. He described himself as ’in excellent physical and mental condition. A sensation of well-being and renewed life flowed through me. Breakfast tasted delicious and was an extraordinary pleasure. When I later walked out into the garden, in which the sun shone now after a spring rain, everything glistened and sparkled in a fresh light. The world was as if newly created. All my senses vibrated in a condition of highest sensitivity that persisted for the entire day. It also appeared to me to be of great significance that I could remember the experience of LSD inebriation in every detail.’

He wrote the report of his experiences and sent it to Stoll, who read it and immediately called Hofmann to ask: ’Are you certain that you have made no mistake in the weighing? Is the stated dose really correct?’ Ernst Rothlin, director of the pharmacology department at Sandoz, had the same questions. Rothlin and two of his colleagues repeated Hofmann’s experiment, but using only one-third of the dose. Even with this reduced dosage, the effects were characterised as ’extremely impressive and fantastic.’ As Hofmann has since put it: ’All doubts in the statements of my report were eliminated’.

Hofmann had discovered LSD’s extraordinary potency. The world would never be the same again. Hofmann says he knew immediately that LSD could be of great value to psychiatry, and until the early 1960s, Sandoz made LSD readily available to scientific and clinical investigators for medical research under the trade name Delysid.

Hofmann soon became a world authority on the chemistry of naturally occurring psychoactive materials. He isolated the active principles of the so-called magic mushrooms of Mexico, which were ritually used by the Indians to get in touch with the gods. He determined the chemical structure of the active principles and developed a synthesis method enabling medical research on them to begin.

Hofmann also analysed psychoactive decoctions that had been prepared by the Aztecs from species of morning glory seeds. Surprisingly, that material proved to contain lysergic acid amides. Thus, investigation into the ceremonies of Meso American Indians led to the discovery that their sacred preparations contained compounds intimately related in structure to LSD and the alkaloids of European ergot.

With a few key collaborators, including amateur mycologist R Gordon Wasson, and Harvard University’s ethnobotanist Richard Evans Schultes, Hofmann co-authored books on ethnopharmacology, and the ritual use of psychoactive materials by other cultures.

LSD soon escaped from the laboratory and became the most widely used psychedelic. It was touted as the cure-all for cultural stagnation by former Harvard professor Timothy Leary with his prescription to ’turn on, tune in, drop out’.

Hofmann thought Leary was intelligent and charming, but also believed that Leary’s need for attention and delight in being provocative shifted the focus from the essential issue of the medical value of LSD. Hofmann was convinced that LSD would be a boon for psychiatry. For him, personally, LSD had provided a deep and mystical experience. He says, with some dismay, ’I never imagined that it could be used as a pleasure drug’.

Did Hofmann’s discovery really change the world? Yes. If the only thing that came from the discovery of LSD was a potent new psychedelic drug that has been used by millions of people, Hofmann’s discovery would still have changed the course of history.

No one today will deny that the use of LSD became intertwined with the culture of the 1960s. LSD helped to catalyse a cultural revolution that led to a whole new vocabulary for describing colours, clothing, art, and music, to name but a few.

LSD also changed attitudes; it tested our cultural values, and helped to push generations into conflict. In the minds of many of my father’s generation, and even many of their children, the use of LSD remains inextricably linked with the Vietnam war protests. Many a frustrated and angry parent believed that using LSD had caused their son or daughter to reject their time-honoured values, or become a war protestor. Thus, for many in the mainstream, LSD even took on an ’anti-American’ character.

Impact on medicine

But Hofmann’s creation did much more than just influence Western culture. It has had a tremendous impact on medicine. In the 1940s, research on the brain was in its infancy. Better biochemical and analytical chemistry tools and techniques were becoming available for biomedical research. Scientists were just beginning to identify and measure the amounts of the various chemicals found in the brain.

The discovery of the profound effects of LSD occurred at nearly the same time as the identification of the molecular structure of serotonin and the detection of its presence in the brain. It was then apparent that serotonin had the same chemical framework that was embodied within the core structure of LSD.

Researchers at numerous laboratories hypothesised that serotonin might play an important role in mental function; that alteration of brain serotonin might be involved in mental illness. Indeed, when Sandoz initially began supplying LSD to scientists, it was provided in the belief that it produced a model psychosis, so that psychiatrists could take LSD and gain a glimpse into the world of the mentally ill.

The connection between mental illness and disturbances of neurochemistry was firmly cemented into place by the discovery of LSD. The idea was extremely controversial and not widely embraced, and the implications were enormous.

This LSD-serotonin connection served as a major catalyst for the revolution in neuroscience that continues unabated today. The role of serotonin in the brain continues to be a topic of extremely high research interest. Drugs that alter serotonin neurotransmission include the new generation antidepressants such as Prozac (fluoxetine), Zoloft (sertraline), and others, which lack the toxic effects of older generation drugs. Modern treatments for migraine are also based on drugs that interact with serotonin receptors. Some of the best drugs to treat schizophrenia also bind to brain serotonin receptors.

In the intense study of brain serotonin systems that followed the discovery of LSD, many new tools, insights, and perspectives were gained that spilled over into related research areas. It is simply impossible to imagine what the neuroscience research world and our understanding of the brain would be like today had LSD never been discovered.

No matter how you feel about the social aspects of LSD, it did have a profound effect on society. More importantly, we can never fully appreciate how different the face of medicine and psychiatry, and our understanding of the brain would be today without Hofmann’s discovery.

David Nichols is professor of medicinal chemistry and molecular pharmacology at the Purdue University school of pharmacy and pharmaceutical sciences, US, and founding president of the Heffter Research Institute, which supports research into the medical uses of psychedelics

Further Reading

A Hofmann, LSD, my problem child, 1980, McGraw-Hill

A Hofmann, Sandoz Excerpta, 1955, 1, 1

LSD research today

LSD, d-lysergic acid diethylamide, has been studied for its potential to treat alcoholics, help terminal cancer patients and rehabilitate convicts.

After Albert Hofmann discovered LSD’s potency in 1943 there was considerable research interest. But this came to an end after LSD was placed under the US controlled substances act in 1970 and classed as a schedule 1 drug, meaning that it was considered to have a high abuse potential and no accepted medical use. By the early 1970s research was almost entirely stopped by regulatory agencies around the world.

The last project, which ran until the 1980s, was Jan Bastiaans’ work in the Netherlands. He used LSD psychotherapy to treat people with concentration camp syndrome.

Currently, there are no legal human studies with LSD, although there are some with other psychedelics such as ecstasy or MDMA (3,4-methylene-dioxymethamphetamine), DMT (N,N-dimethyltryptamine) and psilocybin. It is possible to get permission for human LSD studies from the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and the Drugs Enforcement Agency but it takes time and there is unlikely to be any funding forthcoming.

The FDA has recently approved a human study looking at how LSD affects the brain’s neurotransmitter systems. The institutional review board (IRB), still has to give its approval, which could take until next summer. Until then, the researchers don’t want to reveal any specifics about the study location or design.

Also, Andrew Sewell and John Halpern, at Harvard Medical School, US, are developing a study to look into the use of LSD and psilocybin to treat cluster headaches. They have collected responses from internet questionnaires of people who have used psychedelics to treat cluster headaches and are hoping to submit the project to the Harvard IRB in the next few months and after to the FDA.

Meanwhile, David Nichols, at the Purdue University school of pharmacy and pharmaceutical sciences, US, researches the effects of LSD, and other drugs, on brain neurochemistry and behaviour in rats.

No comments yet