Sodium batteries may have just crossed a critical threshold, moving into high-voltage territory and opening a realistic path toward sustainable, low-cost energy storage.

Unlike conventional lithium-ion batteries, sodium–sulfur batteries store energy using metallic sodium as the anode and elemental sulfur (S₈) as the cathode – two elements that are both abundant and inexpensive. ‘[They are a] much more sustainable and affordable way to store energy,’ says Hao Sun at Shanghai Jiao Tong University in China.

But traditional sodium–sulfur batteries come with serious drawbacks. Most operate only at high temperatures, while room-temperature versions suffer from low voltage, require large amounts of metallic sodium and are flammable.

To address these limitations, Sun and his colleagues introduced a new sulfur chemistry that operates at lithium-like voltages. ‘The key [is] a high-valent redox chemistry of sulfur (S0/S4+),’ says Sun.

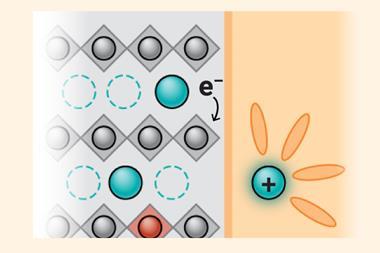

S8 molecules can be oxidised to a higher valence, such as S4+. Reaching these higher oxidation states is highly desirable because they allow batteries to operate at much higher voltages, dramatically increasing how much energy they can store.

‘This chemistry is typically inaccessible in room temperature Na–S batteries because standard battery electrolytes would decompose before the sulfur could be oxidised, and the resulting S4+ species are reactive and soluble,’ explains Serena Cussen at University College Dublin who was not involved in the study.

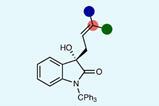

The team overcame this by enabling a reaction between S8 and sulfur tetrachloride (SCl4), which forms in situ from chloride species in the electrolyte with the help of a bismuth catalyst that is incorporated into the S8 cathode.

‘The key enabler here is a sodium dicyanamide (NaDCA) electrolyte,’ says Cussen, ‘composed of NaDCA and AlCl3 in SOCl2. The DCA anion plays a crucial and elegant role: it enables reversible S/SCl4 conversion and improves sodium plating and stripping. The use of highly porous carbon at the cathode further traps SCl4, limiting its dissolution and maintaining electrochemical reversibility.’

‘Reporting 3.6V in room temperature sodium–sulfur allows for significant gains in energy and power density with real potential … for grid level energy storage,’ comments Kevin Ryan at the University of Limerick, also not involved in the study.

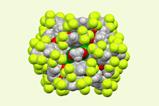

This represents a dramatic leap compared with existing sodium batteries, which typically deliver less than 1.6V. The battery also uses abundant, low-cost materials, including an S8 cathode, aluminum foil as the anode current collector and a non-flammable chloroaluminate electrolyte, enabling an anode-free design. Instead of relying on a built-in sodium anode, metallic sodium forms temporarily on the current collector during charging, reducing cost, weight and safety risks.

These safety gains were borne out in testing: the batteries neither caught fire nor exploded when punctured, and the electrolyte rapidly solidified when exposed to air, preventing leakage.

Together, these advances could reposition sodium–sulfur batteries from a scientific curiosity into a credible, scalable alternative for future energy storage.

‘There will be challenges in scaling this technology, mainly around the corrosiveness of the electrolyte and maintaining the stability of SCl4 as the charged product,’ comments Ryan. ‘However, if these can be surmounted, this work does open a very interesting route to lithium-free storage that crucially does not trade-off performance for cost and sustainability gains.’

Sun says his team is already working to address these hurdles and has already made encouraging progress. He estimates the technology could cost around $5 (£3.62) per kilowatt-hour based on current material prices, although achieving this will depend on successful large-scale manufacturing, with real-world costs likely to vary.

‘We expect small-scale battery products in about three years,’ he adds. ‘If everything proceeds smoothly, real commercial products could appear within five years.’

References

S Geng et al, Nature, 2026, DOI: 10.1038/s41586-025-09867-2

1 Reader's comment