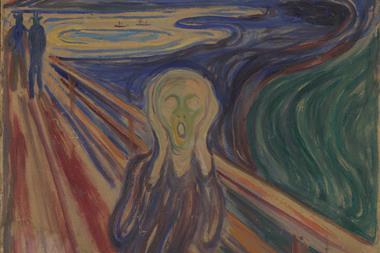

The priceless, porous artwork that adorns the walls of a US university art gallery probably hosts a surprising proportion of the chemicals that have been breathed and sweated out by its visitors, a month-long field study has found.

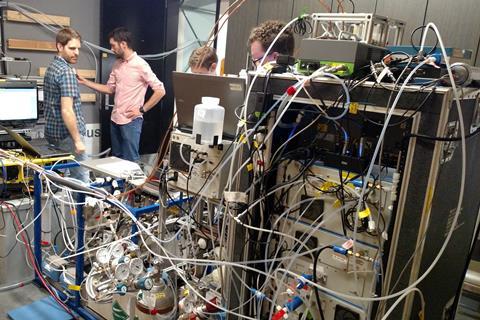

University of Colorado Boulder chemists spent four weeks monitoring the air inside a gallery at their university’s new art museum, looking at levels of volatile and semi-volatile organic compounds, carbon dioxide and other trace gases known to be given off by humans. The proportions emitted by a typical person has been determined by previous studies, here the team wanted to catalogue where these chemicals go – their fate.

‘The team were able to link the chemical properties of the molecules that they were studying to their fate in the indoor environment,’ says analytical chemist Delphine Farmer from Colorado State University, who was not involved in the study.

‘We saw that small, volatile organic molecules such as acetone preferred to remain in the gas phase,’ explains first author Demetrios Pagonis. The speed they were removed from the air inside the gallery therefore matched the room’s ventilation rate. ‘But molecules like lactic acid were getting removed from the air much faster than the rate the indoor air was being ventilated to outdoors. This tells us is that there’s an additional loss process for these indoors.’

Previous work has shown that an alternative fate for indoor air pollutants is sticking to surfaces, but it was thought that only very ‘sticky’ molecules such as plasticisers did this. ‘One of our significant new findings is that the compounds that stick to surfaces are a lot more volatile than people previously thought,’ says Pagonis.

‘This means that when you visit an art gallery you leave traces of your visit deposited on the artwork,’ explains Jonathan Williams at the Max Planck Institute for Chemistry in Germany, who has studied human emissions in locations including cinemas and a football stadium, and wasn’t involved in this work. ‘It [also] highlights how important surfaces are in the indoor environment when it comes to the persistence of chemicals.’

To demonstrate the sensitivity of their analytical instrument set-up, the Boulder researchers looked at alcohol-related emissions during an exhibit opening party when 300 people visited the gallery in a two hour period. The party was an alcohol-free zone, but air measurements showed that approximately 16% of the attendees had consumed one standard alcoholic drink before arrival. ‘When people drink they vent a fraction of the ethanol back to the air, and acetaldehyde increases as the body processes the alcohol,’ says Williams. ‘We have [previously] seen at football matches that goals are often closely followed by an ethanol peak.’

Efforts to unpick how humans inadvertently affect indoor air quality are ongoing, with the Boulder group now looking at the air inside an athletic centre. But this study was able to confirm that the university’s works of art are in safe hands, with all levels of regulated chemicals falling below the standards set by art museum conservation groups.

References

D Pagonis et al, Environ. Sci. Technol., 2019, DOI: 10.1021/acs.est.9b00276

No comments yet