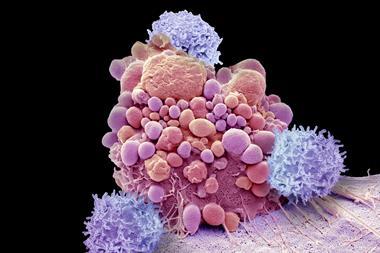

The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has revealed that it is investigating a serious side effect of a revolutionary class of cancer therapies. The agency announced reports of T-cell malignancies in patients receiving CAR (chimeric antigen receptor)-T cell therapies, surprising researchers in the field. CAR-T is often the last resort treatment for patients with blood and blood tissue cancers.

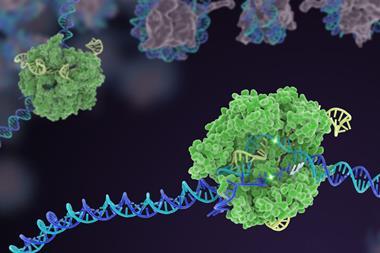

CAR-T requires a patient’s T cells to be extracted and their receptor genetically modified using a viral vector. This programs them to target proteins on the surface of diseased B cells.

CAR-T requires the engineered T cells to be grown up in a lab and reinfused into the original donor. The modified T cell receptor latches onto the target protein and kills cancerous B cells. The first two CAR-T therapies were approved in the US in 2017 to treat a blood cancer.

Patients with no therapy options have been cured by CAR-T therapies, causing great excitement, although costs can be in excess of $350,000 (£260,000) per treatment.

The FDA said it had received clinical trial and post-marketing reports of T-cell malignancies in patients. This risk applies to all currently approved CAR-T therapies, it concluded.

‘Although the overall benefits of these products continue to outweigh their potential risks for their approved uses,’ the FDA said it ‘is investigating the identified risk of T cell malignancy with serious outcomes, including hospitalisations and death, and is evaluating the need for regulatory action.’

The agency listed six approved products under investigation – Abecma and Breyanzi from Bristol Myers Squibb; Yescarta and Tecartus from Kite Pharma/Gilead; Carvykti from Johnson & Johnson; and Kymriah from Novartis.

The possibility of secondary cancers developing after modification of the DNA of T cells using lentivirals or retrovirals had long been a concern. During early clinical trials for an immunodeficiency disorder a therapeutic retroviral vector had inserted genetic material into a pro-cancer gene and caused a leukaemia-like illness.

One possible mechanism in the case of CAR-T therapies is activation of a cancer gene close to the site where the virus integrates, says Michel Sadelain, a CAR-T pioneer at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Centre. Sadelain and colleagues reported earlier this year that disruption of a regulatory gene (TET2) during T cell modification could unleash runaway T cell proliferation. Meanwhile, a recent study profiled how lentivirals and retrovirals can affect CAR-T cell products.

‘It is noteworthy that more of the newly reported cases may have used a lentiviral vector than a γ-retroviral vector, but more data are needed to reach any conclusion,’ says Sadelain. ‘An important mechanism to consider is a genetic predisposition in certain individuals.’

Initial approval of CAR-T by the FDA had required companies to follow patients for 15 years, with observational studies to assess the long-term safety and risk of secondary malignancies. The FDA now says that ‘patients and clinical trial participants receiving treatment with these products should be monitored life-long for new malignancies’.

Gilead said that it had treated 17,700 patients in clinical trials and commercial settings and was not aware of any evidence that Yescarta or Tecartus caused any malignancies. Both Novartis and Bristol-Myers Squibb released similar statements reporting no causal link between their CAR-T therapies and secondary cancers.

Fierce Pharma reported that a search of FDA adverse events revealed a total of 12 T-cell lymphoma cases for Breyanzi, Carvykti, Kymriah and Yescarta.

‘This announcement was surprising to us. We have treated hundreds of patients with CAR-T cells, including over 400 manufactured in our centre, and have not observed any such occurrences,’ says Sadelein. He adds that the incidence of these secondary cancers in around 0.1% of cases should not end CAR-T therapies’ bright future.

Asked what could be done to reduce the risk of secondary cancers, he says: ‘We need to identify the mechanisms to be able to prevent them. One feasible step would be to screen for pre-existing mutations that can promote haematopoietic and T cell expansion.’

No comments yet