Combination strategy developed by BASF and Givaudan is the first complete replacement for animal testing

The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) has approved the first overall testing strategy to predict skin allergic reactions without using animals. The strategy was developed in a decade-long collaboration between German chemicals company BASF, and Swiss flavour and fragrance specialist Givaudan. According to Givaudan’s head of in vitro molecular screening, Andreas Natch, it is better at predicting human allergy risks than traditional animal testing.

Skin sensitisation is one of the potential effects that must be assessed for a cosmetic product. As Robert Landsiedel, vice president of special toxicology at BASF, explains, the team analysed the sensitisation process from a substance’s first contact with human skin to the outbreak of allergic contact dermatitis (ACD) upon repeated contact, and identified several key events that lead to ACD. Various in vitro methods had been approved by the OECD in the past decade for specific key events, but not an overall strategy that could remove the need for animal tests.

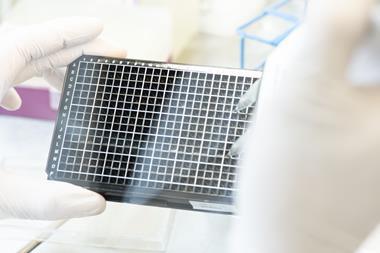

The team found that combining methods to evaluate three of the key events would suffice. The first, the direct peptide reactivity assay, looks at whether the test substance binds to skin proteins (the first step of the sensitisation process) using synthetic heptapeptides as surrogates.

This binding event causes dendritic cells in the skin to migrate to the lymph nodes. The second test, a human cell line activation test, measures changes in the dendritic cells when incubated with the test substance.

The immune system normally only responds to the altered proteins if they also cause stress or injury. A third method uses a cellular stress response pathway linked to a bioluminescence reporter gene, and two luminometer-based methods are available to detect the response.

While combining these three methods can detect if a test substance is a skin sensitiser, quantification of its potency was missing. To address this, the first test was expanded to measure how fast the binding happens. This new kinetic test has now also been adopted by the OECD.

‘For skin sensitisation, unlike almost all other toxicological effects, good human data are available,’ Landsiedel says. ‘Hence, we can compare the results from the standard animal tests and the new non-animal approach to actual human skin-sensitising potential of test substances.’

The OECD’s approval of the strategy was welcomed by Fiona Sewell, head of toxicology at the UK’s National Centre for the Replacement, Refinement and Reduction of Animals in Research (NC3Rs). ‘This is an important step forward in realising the goal of reducing reliance on experimental animals in the safety assessment of chemicals and drugs,’ she says, adding that the new kinetic assay also represents a significant step forward.

Landsiedel says that BASF and Givaudan are continuing to work on other alternative methods, including for reproductive toxicity and respiratory toxicity. ‘Methods and testing strategies on endocrine effects are currently a priority of our alternative method development,’ he says.

No comments yet