Step on the road to sustainable fuel production as iron–porphyrin catalyst comes through under mild conditions

Carbon dioxide can now be reduced to methane using a cheap iron-based catalyst and a bit of help from the sun.1 The process is a promising step towards recycling carbon dioxide and producing fuels from renewable resources.

Methane is burnt in ovens, water heaters and turbines, but is almost exclusively extracted from non-renewable geological sources. Being able to selectively convert atmospheric carbon dioxide into methane and other fuels using a renewable energy source would be a great advance on the way to a low-carbon economy. However, this requires inexpensive and efficient catalysts, but only a few known compounds are selective for carbon dioxide reduction. Also, common catalysts primarily generate products such as carbon monoxide or formic acid instead of highly reduced hydrocarbons.

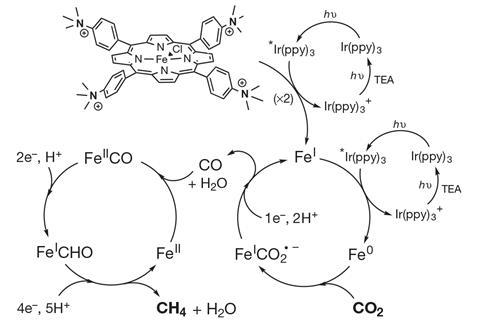

Scientists at Paris Diderot University, France, and the National University of Cordoba, Argentina, have now developed an inexpensive catalytic system that reduces carbon dioxide to methane at ambient pressure and temperature. To mimic sunlight, the researchers used a solar simulator equipped with filters. ‘It is remarkable that the relatively unreactive carbon dioxide is reduced under such benign conditions,’ says Marc Robert who led the study. ‘Using only visible solar light as the energy source, we have transformed this gas into methane with the help of an iron molecule.’ He and his colleagues illuminated a carbon dioxide-saturated solution of acetonitrile containing an electron donor, a photosensitiser and a small amount of the catalyst, which consists of an iron tetraphenylporphyrin complex functionalised with trimethylammonio groups.2,3

Energetic mixture

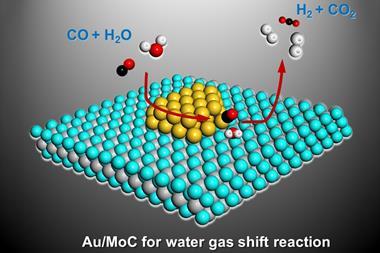

After several hours of irradiation, the scientists analysed the products and found that they had a mixture of methane, carbon monoxide and hydrogen. While carbon monoxide was the main product of the direct reduction reaction, followed by methane and hydrogen, a two-pot procedure generated methane with a selectivity of up to 82%. ‘The authors describe an interesting approach, first converting carbon dioxide to carbon monoxide and then converting the carbon monoxide to methane with high selectivity,’ says Paul Kenis, a chemistry professor at the University of Illinois at Urbana, Champaign, US, who also adds that applying a two-step process is not new. ‘However, the use of earth-abundant iron-based catalysts and the resulting high selectivity for methane in the second step is a significant achievement.’

‘I really like this process,’ says William Mustain at the University of Connecticut, US. ‘The catalysts are reasonably simple to make and inexpensive. Also, using light to enhance chemical reactions is a very interesting area for research. If this can be scaled, it would be huge not only for renewable fuels but lowering the amount of greenhouse gases as well.’

Nate Lewis, who works on solar fuels at the California Institute of Technology, US, agrees that the process could be a step towards the production of carbon-neutral fuels from sunlight, but he says that the product yields, energy efficiency and selectivity of the direct reaction could be significantly improved. ‘Challenges will involve the efficiency and stability of the system, competition from the reduction of atmospheric oxygen, simultaneously effecting efficient water oxidation while achieving product separation, and overcoming the limited flux of atmospheric carbon dioxide at the earth’s surface,’ he says. Kenis points out that the low solubility of carbon dioxide and carbon monoxide in electrolytes might also be a major bottleneck when trying to improve the performance of the system. He thinks that testing the process using a gas diffusion electrode – which facilitates the contact between catalyst and reactants in liquid and gas phase – could help. ‘A simple experiment and the result can be immediately used to assess potential for scale up,’ Kenis says.

Air capture

For the study, the team used pure carbon dioxide from a commercial cylinder, but in the long term, they imagine grabbing the gas directly from air. A problem could be the influence of impurities, says Mustain. ‘Catalyst poisoning and regeneration will need to be considered and will eventually dictate where the carbon dioxide comes from and if the process will be economically viable.’

Robert’s group is now trying to uncover the details of the reaction mechanism. The team know that in the first step, the iron centre binds to carbon dioxide to form Fe-CO2, which is then reduced to carbon monoxide upon cleavage of a carbon–oxygen bond. ‘But the further steps with hydrogenation of the molecule remain mysterious,’ Robert says. ‘It is thus a high priority to understand them if we want to optimise and scale up the process to produce methane in large quantities. A long and bumpy road is still ahead of us.’

References

1 Rao et al, Nature, 2017, DOI: 10.1038/nature23016

2 C Costentin et al, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA, 2015, 112, 6882 (DOI: 10.1073/pnas.1507063112)

3 I Azcarate et al, J. Am. Chem. Soc., 2016, 138, 16639 (DOI: 10.1021/jacs.6b07014)

No comments yet