Rising antibiotic resistance caused by pollutants needs action

Our environment is contaminated with antibiotics. While this is often at a dilute level, sometimes the concentrations are surprisingly high. There is a growing recognition that this is a public health issue.

Antibiotic resistance accounts for hundreds of thousands of deaths each year and is a major global health threat. While attention has focused on antibiotic overuse, hospital outbreaks and new drug-resistant superbugs, antibiotics in waterways and soils is now viewed as stoking a rise of antibiotic resistance.

How do bacteria become resistant to antibiotics?

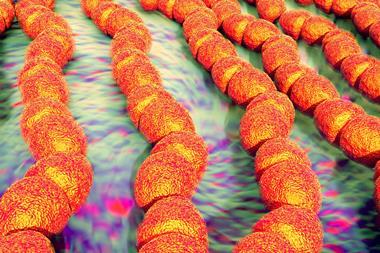

Mutation and evolution. Much of the resistance in disease-causing bacteria originate from existing genes. Antibiotics are part of many microorganisms’ natural armoury, so all sorts of resistance genes have always existed. What has changed is that these genes, one by one, jump from harmless bacteria to those that cause disease.

A bacterium may mutate and gain a small advantage in the presence of an antibiotic. And a gene that confers a competitive advantage can spread fast amongst bacteria because of their high rate of replication.

Having locations where bacteria can mingle in a thin soup of antibiotics and resistance genes is a recipe for resistance transferring between different species… and potentially creating new superbugs.

Where do antibiotics in the environment come from?

When we use an antibiotic, typically between 30–90% of the active compound will get excreted and flushed down the loo. This means sewage plants are chock full of a city’s medicines. But humans are not the only source. Globally, two-thirds of antibiotics produced are used on animals. They secrete them onto land and into slurry pits, which can run off into rivers, lakes or groundwater. In low- and middle-income countries, fish farms also produce antibiotic waste. And finally there is waste from pharmaceutical factories, which can also pollute waterways.

Why should we be concerned?

Blanketing the environment results in conditions that encourage bacteria to evolve ways to protect themselves. Worse, these bacteria, most of which are strains harmless to humans, can then share this resistance mechanism with disease-causing microbes. Antibiotics also offer a competitive advantage to any bug that already has a ready-made antidote or is unaffected by that particular drug, resulting in blooming populations that would otherwise have been kept in check.

The exposure of microorganisms to chronically low levels of biocides and metals is also suspected to boost the number of antibiotic resistant bacteria. This can be a result of cross-resistance, where one gene protects against multiple threats to the bacterium – including the drugs used to kill it and potentially save a patient’s life.

How big a contribution is the environment making to the rise of resistant bacteria?

The precise contribution cannot easily be quantified as tracing back where a resistance gene came from is extremely difficult. However, in 2017 the United Nations warned that the release of antibiotics in the environment was driving bacterial evolution and the emergence of more resistant strains. Wastewater treatment plants cannot remove all the antibiotics and the WHO noted that multi-drug resistant bacteria are prevalent in sediment near industrial and urban discharges.

Are there any examples of resistance moving from environment to patients?

In 2015, resistance to colistin (an antibiotic of last resort) was detected in E. coli bacteria from pigs, pork products and people in China. It is possible this emerged in bacteria found in pigs, which ultimately moved into human bacteria. Variants of the colistin resistance gene have since been detected all around the world, although it is not certain where the resistance first arose. Several other resistance genes to other antibiotics seem to have arisen from aquatic bacteria.

Are there hot spots for antibiotic pollution?

Yes. Concentrations of antibiotics in a river near manufacturing plants in India and China have been found to be higher than needed to treat a patient. For instance, the antibiotic ciprofloxacin was recorded at 31mg per litre in effluent entering a river in India, a million times greater than levels usually found in sewage outflows. Modern sewage plants have levels of antibiotics in the nanograms or micrograms per litre, and may provide fertile conditions for resistance to emerge. And, as sludge from plants is often spread on agricultural land, it offers an easy route for people, domestic and wild animals to encounter drug-resistant bacteria.

What can be done?

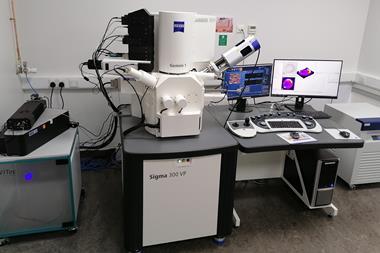

One solution is to take a precautionary approach and minimise concentrations as best we can. There have been positive developments. In April 2017, India announced it would regulate antibiotic discharges from drug makers within three years. Some companies have also committed to voluntary restrictions. GlaxoSmithKline has promised to have suppliers comply with its standards too. Greater transparency will help. Wastewater treatment plants can also be upgraded with new technology, such as ozone treatment, to more thoroughly clean the water.

The unresolved over-use of antibiotics by people has been in the spotlight, but the huge quantities needlessly applied in farming and aquaculture get less attention. Better stewardship can slow the rate of emergence of new superbugs. Improved DNA detection will also help to monitor resistance genes in the environment and allow us to prioritise the steps needed to tackle the problem.

Acknowledgment

The author would like to thank Andrew Singer, NERC Centre for Ecology & Hydrology, UK, and Joakim Larsson from the Centre for Antibiotic Resistance Research at University of Gothenburg, Sweden.

No comments yet