Sequential C–H activations open up the opportunity for an unusual transformation

I have never believed that all academic research should have real-world applications. Despite my day job as a process chemist, my sole criterion for picking papers for this column is that they showcase interesting chemistry, practicality be damned. Of course, the authors of these research articles will always remind you of the biological activity of their targets, the large number of drugs that are natural product-derived, or the way target-oriented synthesis can drive the development of new reactions. However, I’d guess that most of the time, total synthesis is done for fun rather than for practical reasons.

That said, I’m surprised how wounded academic researchers often look when I tell them that we don’t use their exciting new methodology in industry.1 Of course, it’s rarely personal; it’s just that we want reactions that are either efficient and practical (in the case of process chemists) or general and convenient (in the case of medicinal chemists), and new chemistry is rarely any of these things, as much as authors might sprinkle these adjectives into their papers.

On its face, C–H activation seems like it could fall into both of these classes. After all, what could be more efficient than directly changing C–H bonds into the functional groups that you want? However, over my decade in industry, I can’t recall a colleague ever running a transition metal-catalysed C–H insertion. The problem is that while these reactions do sidestep the need for pre-activation of the reaction site, they often still require a directing group that must be installed before and removed after the reaction of interest, dramatically detracting from the overall elegance of the approach. Other frequent drawbacks include high loadings of precious metals, questionable selectivity and a relatively small pool of groups that can actually be introduced directly.

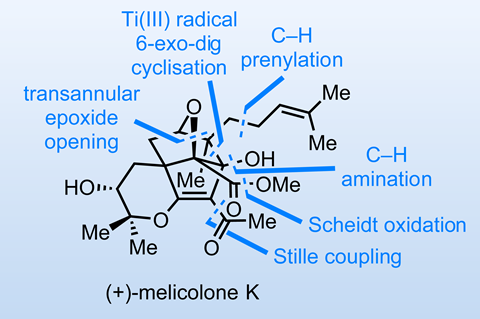

Perhaps for some of the same reasons, I don’t think I’ve featured this class of reaction much in this column. However, a recent synthesis of melicolone K by Ziqi Jia and coworkers at Zhejiang University in Hangzhou, China, is built around two sequential C–H activation reactions that prove highly enabling.2

Before we get to that, the group first assembles the tetracyclic core from a simple achiral cyclohexadienone. With a bicyclic ether in hand, reductive radical cyclisation closes the third ring. After eliminating the primary alcohol, epoxidation of the exo-methylene group and transannular etherification complete the caged core of the molecule (figure 1).

After sulfamate installation, it’s time for the C–H activation steps (figure 2). First, a Dubois-type rhodium-catalysed amination directly installs an amine group on the rather sterically hindered core. Although the new amine will ultimately be replaced by an acetoxy group via diazotisation in acetic acid, it is first used to direct an even more remarkable palladium-mediated C–H functionalisation on the adjacent equatorial methyl group. Under seemingly simple conditions, a formal (4 + 2) cyclisation with isoprene forms a piperidine, which can then be reductively opened. Overall, this accomplishes direct prenylation of an unactivated methyl group, an unusual transformation that I probably wouldn’t have planned a synthesis around!

From here, a handful of functional group interconversions complete the target. Interestingly, the endgame showcases a pair of uncommon oxidations: a Stahl-inspired air-driven oxidation of a primary alcohol and a Scheidt-type NHC-catalysed conversion of an aldehyde directly to the methyl ester. Congratulations to the team on an elegant synthesis that features interesting chemistry throughout!

References

1 For a serious discussion of the academia-industry disconnect, see: D Schultz and L-C Campeau, Nature Chemistry, 2020, 12, 661 (DOI: 10.1038/s41557-020-0510-8). Or, if you’re busy, just look at Figure 2.

2 Z Jia et al, J. Am. Chem. Soc., 2026, 148, 2119 (DOI: 10.1021/jacs.5c20001)

1 Z Jia et al, J. Am. Chem. Soc., 2026, 148, 2119 (DOI: 10.1021/jacs.5c20001)

No comments yet