Meera Senthilingam

This week, what do scientists in Stockholm and Quentin Tarantino have in common? Revealing all is Lars Öhrström:

Lars Öhrström

In Quentin Tarantino's 1994 movie, Pulp Fiction, gangster hit-man John Travolta saves the life of his boss' wife, played by Uma Thurman, by slamming a syringe of adrenaline into her heart. It is interesting, or perhaps disquieting, that among all of Tarantino's blood splatter, this is the scene many people find the hardest to watch.

Some 50 years earlier, during the Second World War, a similar scene was unfolding in the badly ventilated basement of a grey and anonymous building of what was then the university blocks in central Stockholm. Two young men sat opposite each other, one of them shirtless with a black circle inked on his chest, and between them, a syringe full of adrenaline solution.

Although this scene took place in the midst of a city then infested with spies and other clandestine operators, the bare-chested man, a student named Bengt Lundkvist, was not tied to his chair being subjected to interrogation. Instead, Lundkvist and his friend and colleague, Nils Löfgren, were testing the preparations of the Stockholm University organic chemistry group led by the young Löfgren.

Lundkvist had just injected in himself with a solution of white crystals, prepared by the female member of the team, Inga Fischer. The compound, at that point known simply as LL30, was a new anaesthetic and occasionally during these unauthorised tests, Lundkvist's pulse would drop below 25 beats per minute and Lundkvist himself would drop to the floor. But no matter - Löfgren would then invigorate him with a shot of adrenaline, as he matter of factly told the audience in a 1963 television show. LL30 was quite safe, however, and the two scientists soon went on to try out different concentrations and preparations, mostly on their fingers, although their successful experiments did have the awkward side effect of making the bike ride home difficult.

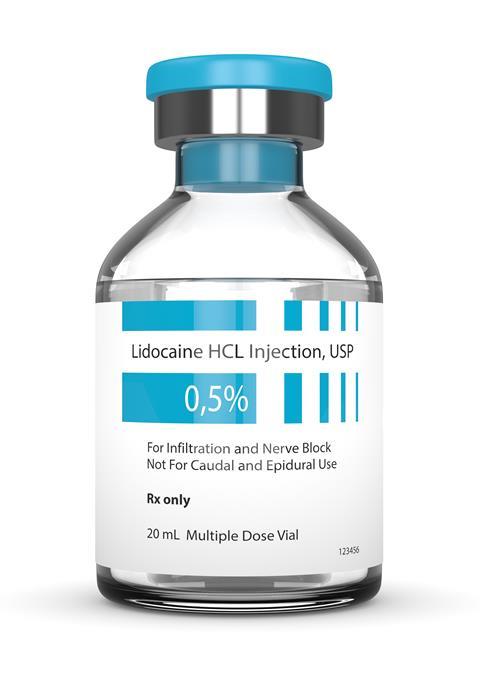

This compound is known today as lidocaine and its pain-relieving properties have probably cured more than a few people of their dentophobia, thanks to its extensive use in dentistry. A dose of lidocaine will make your mouth go numb so that you feel no pain from the dentist's drill. The molecule has been used as an anaesthetic since 1949 and was originally marketed as xylocaine because it can be thought of as a derivative of the aromatic compound xylene. Most often we encounter it in the dental clinic, but also in other types of local anaesthesia by injection or as a cream. Another use is as an antiarrhythmic drug, and in this role it gained some fame by curing US president Eisenhower's heart problems in 1960. There are also other indications, as the medical professionals say, for this drug, but quite which one prompted the physicians of Pope Pius XII to administer lidocaine as a cure for his Holiness' hiccups is not clear. Nevertheless, it remains another feather in this molecule's cap.

Following their successful (if somewhat irregular) trials, Löfgren and Lundkvist sold the rights to a small pharmaceutical company in Södertälje, just south of Stockholm, for a small sum but a hefty deal in subsequent profits.

That company, Astra, went on to become a pharmaceutical heavyweight, merging with UK based Zeneca in 1999. At one point during the 1950s, Löfgren had one of the highest taxable incomes from work in Sweden, probably higher than the CEO of Astra at the time. This seems unthinkable in our times of fat cats and overpaid board room executives.

In his doctoral thesis, Löfgren describes lidocaine as a 'synthetic drug', a word that nowadays makes some people suspicious. They prefer 'natural' alternatives but in this case that would be inadvisable, as the all-natural alternative to lidocaine is cocaine. The truth is that although lidocaine is not naturally occurring, as far as we know, this substance and the whole class of anaesthetics to which it belongs, are closely modelled on the naturally occurring cocaine, but having none of this molecule's undesirable side effects.

Before lidocaine, the standard anaesthetic was another relative of cocaine: novocaine. Lidocaine was a major improvement on novocaine, as novocaine was unstable in water and so had to be freshly prepared before each use - a very time consuming procedure. In lidocaine the presence of a peptide bond where novocaine has an ester bond makes lidocaine much more stable in water.

The particular targets of this anaesthetic family are the proteins making up the ion channels in neurons. Lidocaine and its chemical cousins block these channels to hinder the transport of sodium ions, the means these cells use for transmitting the pain signal.

Lundkvist did not enjoy fame and fortune for long, dying from an accident in 1953, apparently unrelated to the many experiments he performed on himself. Löfgren, on the other hand, had a short career as a professor of organic chemistry in Stockholm, but resigned in 1964 in apparent disgust over the decline of the Swedish university system in general and the increased administrative load of researchers and teachers in particular. He passed away a few years later. In an interesting twist of fate, the chemist who first synthesised this molecule, Inga Fischer, went on to become a legendary professor of theoretical physics at Stockholm University and died at the age of 90 in 2008, seven years after AstraZeneca had sold most of its lidocaine business. But by then Löfgren's and Lundkvist's patent had long since expired.

Meera Senthilingam

So a fair bit of drama and excitement behind this otherwise calming sedative sompund That was Lars Öhrström from the Chalmers tekniska högskola in Sweden with the stroy and chemistry of lidocaine. Now, next week: the compound keeping us fresh all day long.

Josh Howgego

I recently spoke with a fragrance scientist and she explained that for a customer to feel they're getting good value from their deodorant, they want to be able to smell it for as long as possible. To do that, it's important that the fragrance chemists get a good balance of odour molecules in the product, so that they evaporate into our noses in a constant stream over the course of the day - not too quickly, but fast enough that we notice them.

The goal these days though, is to go even further and create 'smart' fragrances that can provide a booster hit of scent when needed. In an ideal world, smart fragrances would be able to start releasing a higher frequency of pleasant-smelling molecules as you start to exercise, for example.

Believe it or not, cyclodextrins hold the answer to this need.

Meera Senthilingam

And to find out how, join Josh Howgego in next week's Chemistry in it's element. Until then, thank you for listening. I'm Meera Senthilingam

No comments yet