Meera Senthilingam

This week, podcast regular Brian Clegg is sweetening things up

Brian Clegg

It seems unlikely that the name of a chemical compound could also be an adjective. A few are twisted into adjectival form - watery, for example - sugary or salty. But the subject of this podcast is an adjective in its own right - and it's not a very positive one. Benzoic sulfilimine takes its common name from the word sacharrine (with an 'e' on the end), meaning 'excessive sweetness'. To call something saccharine is to suggest that it is too sweet; that it's sickly and unattractive. And yet this is exactly the property that made the world's first artificial sweetener such a success.

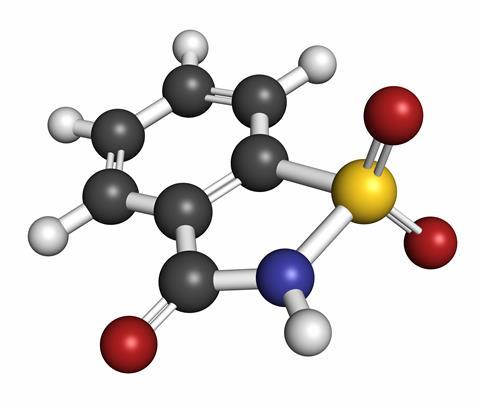

C7H5NO3S was patented as saccharin by Constantin Fahlberg in 1884 and is a wonderful example of an accidental discovery. Fahlberg had returned home from a day working on compounds derived from coal tar at Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore. Eating something with his hands, he noticed a sweet taste on his skin, which he guessed might be caused by the compound he was working on. This was in 1879, and five years later, Fahlberg patented his discovery: the perfect example of an ingenious inventor making a fortune from a serendipitous occurence. Except this is only one version of the story.

The alternative history of saccharin has the head of Fahlberg's lab, Ira Remsen making a very similar observation to the one in Fahlberg's story while eating a bread roll. In this version, it was he who went back to the laboratory and tracked down the sweetness to benzoic sulfilimine.

Whoever really found saccharin to be finger-licking good, the fact remains that, although the pair published the finding together, it was Fahlberg who took out the patents, not Remsen. By then Fahlberg had left the university. Remsen is said to have remarked 'Fahlberg is a scoundrel. It nauseates me to hear my name mentioned in the same breath with him.'

Oddly, the Oxford English Dictionary gives a third heritage for the compound and its name. It claims that the substance was 'discovered and named by P?ligot in 1880.' Eugene P?ligot certainly did work on 'saccharine' (with an E) materials and in 1879 he produced a crystallised lactone which he thought (incorrectly) was an isomer of sucrose and to which he gave the name saccharin - but he was not involved in the compound of our story.

It was shortages of sugar during the first world war that really saw saccharin take off as a sugar substitute that stayed in use when the war ended. But it was in the 1960s and 1970s that saccharin reached its zenith, when the idea of counting calories was taking hold in Western countries obsessed with diet. Because it sweetens with zero calories, it seemed an excellent alternative to sugar, although its bitter after taste has always limited its appeal. Little pink packets with brand names like Sweet'N Low began appearing on cafe tables alongside the sugar.

You'll still find those pink packets, and it is still used in food manufacturing but sacharrin has had a bumpy legislative ride over the years. As early as 1907 it was investigated in the US, not for potential health problems but because it was a low price substitute that devalued sugar-based products. Since then there have been a number of cancer scares, but these were based on experiments with rats, and there have been no equivalent discoveries with primates. Countries that did ban saccharin have now largely restored the compound as a safe product for use in foodstuffs.

In practice, the substance we encounter is likely to be a sodium or calcium salt as the pure acid form does not dissolve in water. It also tends to be mixed with other artificial sweeteners, as each compound has different taste issues, and the mix tends to balance out the bitter aftertaste of saccharin. Another reason for these mixes is varying lifespans - saccharin has a longer shelf life than the more popular aspartame, so is sometimes included to keep a product sweet as aspartame loses its impact.

Artificial sweeteners like saccharin are not going to go away. Not only can they be produced more cheaply than sugar, they have real health benefits. They allow those suffering from diabetes to satisfy their natural craving for sweet food - which seems to be an ancient response to detect energy content in foods (and the absence of toxins). And for those looking to lose weight, the idea of sweetness without calories attached will always be attractive.

These days saccharin is less popular at the tea table. Aspartame has taken over as the artificial sweetener of choice, and sugar remains the best for flavour. But saccharin will never be forgotten because of its unusual position as the adjectival compound.

Meera Senthilingam

So, despite a decrease in popularity, when thinking of sweetness, this compound will always come to mind - and to the dictionary. That was science writer Brian Clegg with the sickeningly sweet chemistry of saccharin. Next week, we go nuclear!

Phillip Broadwith

To make it, you either have to react uranium metal with elemental fluorine, or take purified uranium ore, dissolve it in nitric acid, treat it with ammonia and then reduce it with hydrogen to make uranium dioxide. Reacting that with hydrofluoric acid makes UF4, and finally oxidising with fluorine gas makes UF6. Neither of those are processes I'd be too keen to try in a hurry!

Meera Senthilingam

And to find out why scientists do endure this process, and the uses of uranium hexafluoride in nuclear reactors and bombs, join Phillip Broadwith in next week's Chemistry in its element. Until then, thank you for listening, I'm Meera Senthilingam.

(Promo)

Chemistry in its element comes to you from Chemistry World, the magazine of the Royal Society of Chemistry and is produced by thenakedscientists dot com. There are more compounds that count on our website at chemistryworld dot org slash compounds.

(End promo)

No comments yet