The global market for alternative products based on ‘green’ chemistry is growing fast, fuelled by regulation and consumer demand

The market for so-called ‘safer chemistry’ is set to outpace the overall global chemical market during the current decade. Companies are reducing their use and generation of hazardous substances, creating safer products and lowering the impact of processes on human health and the environment. The impetus comes from a combination of tightening regulations and demand from consumers for more sustainable products.

A recent report, conducted by Trucost for the American Sustainable Business Council and the Green Chemistry & Commerce Council says the global market for ‘green chemistry’ – defined to include biobased chemicals, renewable feedstocks, polymers produced using more sustainable chemistry and less-toxic formulations – is projected to grow from $11 billion in 2015 to nearly $100 billion by 2020.

Although the report says investment in safer chemistry is ‘nascent and difficult to quantify,’ there are signs that it is growing. For example, the number of US patents for more sustainable chemistry jumped from 27 in 2000–2004 to 761 in 2010–2014. This indicates increasing momentum and evolving industry capacity, the report said.

Bend, don’t break

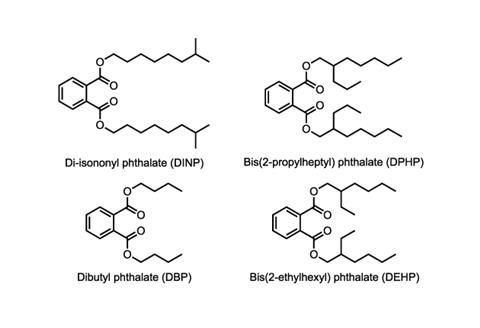

The example of phthalate plasticisers is a good case study to highlight these phenomena. In response to concerns about plasticisers leaching out of products that infants and children put into their mouths, companies have developed molecules that work as plasticisers but have higher molecular weight that helps them to stick more effectively inside the polymer structure and not leach out.

The European Council for Plasticisers and Intermediates (ECPI) says the plasticisers market is strongly influenced by the EU’s Reach (Registration, Evaluation, Authorisation and Restriction of Chemicals) legislation and other EU chemical regulations. ECPI spokesperson Michela Mastrantonio notes that 12 low molecular weight phthalates have been identified in Europe as substances of very high concern (SVHCs) and placed on the Reach Candidate List, which triggers various information requirements and means that they may subsequently be phased out.

ECPI data from the last 15 years show that use of higher molecular weight orthophthalates like di-isononyl- (DINP), di-isodecyl- (DIDP) and bis-(2-propylheptyl) (DPHP) phthalates has significantly increased, while consumption of classified orthophthalates like di-butyl- (DBP) and bis-(2-ethylhexyl) (DEHP) phthalates has decreased. In parallel, non-phthalate plasticisers like di-isononyl cyclohexane dicarboxylate (DINCH) and less problematic para-isomers like di-octyl terephthalate (DOTP) have become more prominent.

Beyond plasticisers, other recent examples of products being chemically reformulated to make them less toxic and greener include the yellow and red pigments based on heavy metals like lead, chromium (iv) and cadmium, with azo-pigments, according to Ciara Dempsey, a regulatory affairs specialist with the Royal Society of Chemistry.

Dempsey also points to the lead-free solder that has been introduced following the EU waste electrical and electronic equipment (WEEE) and restriction of hazardous substances (RoHS) directives. These aim to promote recycling and re-use of materials, while also preventing the use of substances considered hazardous to human health or the environment.

More recently, Dempsey notes, many personal care companies have agreed to stop using plastic microbeads, which can end up in the marine environment and are thought to act as a vector for persistent organic pollutants. ‘This is an example of companies working more pro-actively rather than reactively to regulation,’ she says.

Libby Bernick, Trucost’s senior vice president for North America, points to other examples of products in which chemicals are being substituted for less objectionable alternatives. For instance, she says Construction Specialties has begun manufacturing non-PVC wall coverings and other building materials for use in hospitals, where volatile chemicals emitted from PVC items can affect indoor air quality. The company uses an engineered copolyester made from glycol-modified polyethylene terephthalate (PETG) for these applications.

In addition, Bernick cites Johnson & Johnson’s reformulation of over 100 of its health and beauty products to eliminate ingredients of concern, including formaldehyde-releasing preservatives like quaternium-15. She says Adidas and Puma have pledged to remove polyflourinated chemicals from their clothing.

There are various reasons why companies are making substitutions towards safer chemicals, but regulation is generally the main driver especially in the UK, according to Dempsey. However, she also says re-branding and marketing issues could be a motivator for some companies, especially when they are under pressure from campaigners or consumers.

No comments yet