2025 was another eventful year for the Chemistry World team as we’ve sought to keep on top of the issues that matter the most to those working in the chemical sciences. It’s obviously impossible to revisit absolutely everything that happened over the last 12 months, but here’s a recap of some of the year’s biggest stories.

UK chemistry departments in crisis

A major story in recent years, and something that continued in 2025, has been the slew of announcements from UK chemistry departments on plans to downsize, cut courses, merge with other departments or close down entirely. With university budgets under severe pressures, many institutions are viewing chemistry – traditionally an expensive subject to teach – as an easy area to make savings.

This year, the University of Bradford announced that it would close its chemistry courses, while Cardiff University and the University of East Anglia both unveiled plans to reduce faculty numbers. Cardiff has also confirmed plans to merge its school of chemistry with two other departments from the start of the next academic year. Uncertainty also surrounds the future of chemistry provision at the University of Sheffield and the University of Leicester due to financial difficulties.

The latest cuts to chemistry departments followed a string of similar announcements made last year by other UK universities. The ongoing crisis has caused the Royal Society of Chemistry to warn of the emergence of ‘chemistry cold spots’ across the UK where the subject cannot be studied within a reasonable travel time. The organisation notes that this trend will hit students from lower socio-economic backgrounds the hardest. The RSC also warns that the reduction in the provision of chemistry skills could have consequences for the government’s industrial strategy.

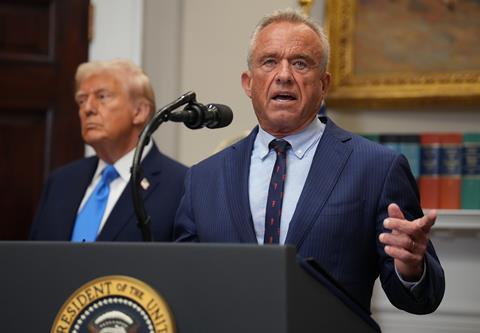

Trump 2.0 brings chaos to US academia

Almost immediately after coming to office in January, Donald Trump’s administration launched an assault on the country’s research enterprise, marking the start of a deep uncertainty for universities, funders and researchers.

A federal hiring freeze, followed by swingeing cuts to the federal workforce enacted by Elon Musk’s Department of Government Efficiency paralysed work at funding bodies like the National Science Foundation and the National Institutes for Health. Meanwhile, the administration’s drive to eliminate federal support for any form of diversity, equity and inclusion, as well as specific topics like mRNA vaccines, saw research grants cancelled, rewritten and rescrutinised.

Several measures that sought to reduce the amount of federal support for ‘indirect research costs’ – covering things like lab maintenance, utility bills and the management of hazardous materials – drew immediate legal action and criticism from the academic community. At the same time, individual universities found themselves locked in individual legal battles with the federal government over decisions to terminate billions of dollars of research funding.

As the administration cracked down on inward migration, many foreign students and researchers found themselves targeted. In terms reminiscent of the ‘China Initiative’ that operated during Trump’s first presidential term, in May the administration said it plans to ‘aggressively revoke’ Chinese students’ visas.

Generative AI poses headaches for publishers

The emergence of easily accessible AI tools like Chat GPT and Microsoft’s Copilot continued to dominate news headlines. For chemists the tools offer many benefits in terms of making computational research more accessible, and providing new ways to probe large datasets. But these tools are also a double-edged sword – in particular they bring new challenges for peer reviewers and chemistry educators, with fears growing that the chemistry literature is at risk of being flooded with AI-generated slop.

In September, nanomaterials researchers asked 250 of their peers to distinguish real microscopy images from fakes produced using AI tools. The results suggest that it is now impossible to do so, even for experts. The experiment implies that AI-generated images could make research fraud near undetectable, posing an existential threat for many areas of science.

The following month, researchers called for the chemistry community to ban the use of generative AI for drawing chemical structures. Audrey Moores and Vânia Zuin Zeidler highlighted images used in chemistry journals and others widely shared on the internet that included nonsensical chemical structures. Speaking to Chemistry World, Moores warned that ‘for the first time, [AI has] started to create representation of chemistry that have not come from a thoughtful and [considered] decision from chemists’. The calls shone a spotlight on the shoddy efforts from tools like Chat GPT, Microsoft Copilot and Google Gemini, which fare poorly when asked to draw simple molecules.

October also brought a first-of-its-kind settlement, with AI company Anthropic reaching a deal to pay $1.5 billion (£1.1 billion) to authors of books – including many academic titles – that were downloaded from pirate websites and used to train the company’s Claude models, without the authors’ consent.

Iupac projects grab headlines

2025 has been a busy year for the body that rules on chemistry’s terminology and definitions. In June, 20 prominent experts on per- and poly-fluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) voiced serious concerns about a new International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry (Iupac) project to redefine PFAS. With numerous definitions being used by different states and bodies, the Iupac project committee hopes to provide clarity that could help ‘national and global regulation’. However, its critics question the motives behind the project, and fear that any new definition that is narrower than the current Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development definition – which is used by many policymakers – could lead to less effective regulation.

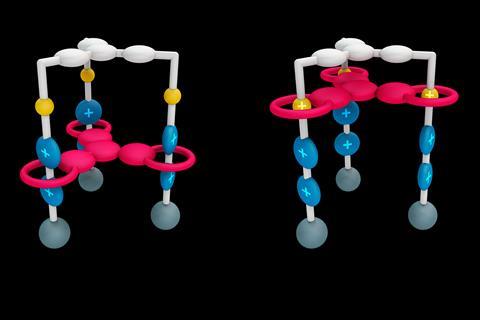

Another Iupac project is seeking to define the key terms used by researchers working on molecular machines. The project team want to end semantic debates that have dogged the field and provide clarity in the event of any future legal battles that involve the technology. However, speaking to Chemistry World in April, the University of Manchester’s David Leigh – a trailblazer in the field – noted that terms like molecular pump and molecular motor are widely used by scientists in many different disciplines, and so any new definitions would need to be consistent with these wider uses and should avoid being too prescriptive.

This year, Iupac also unveiled a set of ‘guiding principles for responsible chemistry’ that it hopes will encourage chemists to practise their work safely and sustainably, while upholding values of inclusivity, integrity and accuracy. The organisation hopes to spark a conversation about the ethical dimensions of chemistry, and is keen to reach the next generation of scientists by getting the new principles into undergraduate textbooks.

Challenging situation for research funders

Across the globe, governments have been tightening budgets, putting research funders in a difficult position. In Europe researchers raised the alarm and even staged protests against cuts to research funding that have been announced in numerous countries that are considered some of science’s major powerhouses. The Netherlands, France, Italy, Germany and Switzerland have all announced cuts to research funding. Meanwhile Serbian scientists were ordered to spend no more than five hours a week in the lab amid a broader dispute with the country’s government.

In the UK, the government did announce the return of 10-year budgets for research funders to try and provide some stability. However, UKRI was faced with a real-terms cut to its budget (after having already promised PhD students their biggest pay rise in over 20 years).

Meanwhile, the UK government’s health department opted to pull its support for the Fleming Fund, with critics saying the move would threaten global efforts to fight antimicrobial resistance. The £256 million initiative ran for 10 years, supporting efforts to build lab capacity and data sharing in low- and middle-income countries. A government spokesperson told Chemistry World that the decision to end the programme was taken to ‘fund a necessary increase in defence spending’.

Warnings over UK visa policy

Throughout the year, numerous organisations have sounded the alarm over the UK’s visa system. With the Labour government eager to appease persistent calls from the right to reduce immigration, new policies are making it even harder for international students and researchers to come to the country. Various groups highlight that with the UK in a global fight for top talent, these policies are harming universities’ abilities to attract the brightest and best.

In February, the House of Lords’ science and technology committee described the UK’s approach to attracting scientific talent as ‘an act of national self-harm’. Speaking to Chemistry World in August, Edmund Derby from the Campaign for Science and Engineering pointed out that the number of visas granted for science, research and engineering roles during the second half of 2024 was one third lower than in the same period a year earlier. In October, an analysis by the Royal Society showed that upfront costs for researchers seeking to move to the UK are up to 22 times higher than the international average.

Earlier in the year, the presidents of 21 international science unions published an open letter calling on immigration authorities worldwide to ‘favourably consider’ awarding entrance visas to scientists. They noted that scientific collaboration is essential for addressing humanity’s biggest challenges and provides economic benefits for the countries involved.

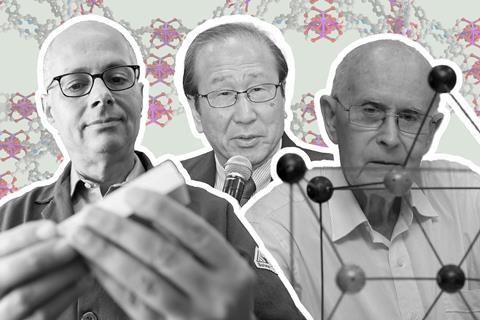

Nobel prize for MOF pioneers

In October, the Nobel committee opted to honour Richard Robson, Susumu Kitagawa and Omar Yaghi with this year’s chemistry prize for their work on metal–organic frameworks (MOFs). In particular, the Nobel committee highlighted Robson’s early work demonstrating how these structures could be designed, while Kitagawa and Yaghi were credited for a series of milestones that showed how the materials’ exceptional porosity could be fine-tuned and put to good use.

It’s a topic that had been tipped for a Nobel for many years. When Robson first published his initial ‘coordination polymer’ in 1989, just 100 or so structures that could be described as MOFs had ever been studied. Today that figure stands at over 100,000 and a raft of companies have started working towards commercialising products based on these highly porous materials. From carbon capture to hydrogen storage, MOFs offer a way to tackle many great challenges – time will tell just how effective they prove to be.

Speaking to Chemistry World shortly after the Nobel announcement, Kitagawa noted that while some of his peers had described his early MOF research as ‘boring copper(I) chemistry’, it had turned out to be a ‘gold mine’.

PFAS: the problem that won’t go away

Barely a day goes by without a new report relating to PFAS, and it’s hardly surprising given the ubiquity of these ‘forever chemicals’. The compounds, which are widely used in non-stick cookware, firefighting foams and waterproof clothing, have been detected in drinking water the world over, and 99% of us have them in our blood. This year evidence has emerged that they may even be more acidic and, therefore, more mobile than had previously been thought.

In January, a YouGov poll commissioned by the Royal Society of Chemistry found that 90% of the UK public believe that it is ‘very important’ that PFAS are controlled in food, drinking water and the environment, but less than a third trust the government to take action.

In February, PFAS were linked to livestock deaths and illnesses among agricultural workers in Johnson County, Texas. High levels of PFAS were detected in the environment and in the bodies of farm animals, fish and farmers, which many believe is due to the use of fertiliser derived from PFAS-contaminated sewage sludge.

That same month, France became just the second country to ban PFAS in certain products – in this case, cosmetics, textiles and ski wax. While campaigners welcomed the ban as a start, many noted the need for broader regulation at the multinational level.

Meanwhile, three UK military bases – RAF Marham in Norfolk, RM Chivenor in Devon and AAC Middle Wallop in Hampshire – were accused of leaking high levels of PFAS into local drinking water sources.

Environmental protection efforts struggle against realpolitik

Planet Earth is faced with numerous pollution challenges that its inhabitants have caused and are struggling to control. While many multinational efforts are underway to tackle various forms of chemical pollution, most are hitting familiar stumbling blocks.

This year, the UN established a new scientific panel to provide authoritative advice on chemical pollution. The panel is to function as an equivalent of the IPCC and IPBES – the bodies that provide policymakers with guidance on climate change and biodiversity loss. But while several years of negotiations between UN member states have finally led to the establishment of the chemical pollution panel, there is still little agreement on exactly what the panel’s scope will be, who will be appointed to it, how it will be financed and how it will avoid conflicts of interest.

Meanwhile efforts to negotiate a global agreement to end plastic pollution have yet again failed to reach consensus on the treaty’s text. While a majority of countries want the treaty to address the full plastic lifecycle, including measures to curb production and phase out toxic additives, a smaller set of countries with large petrochemical industries have blocked any agreement. As the latest talks broke down in August, one delegate noted that the majority of countries’ red lines had been ‘stomped, spat on and burned’.

Even in cases where controls have been agreed on harmful chemicals, complications still arise. In October, an investigation by Public Eye, Unearthed and Greenpeace UK revealed that almost 122,000 tonnes of pesticides that are banned in the EU had been exported by companies in the bloc last year. The figure is up 50% since 2018. One expert told Chemistry World that the findings represent an ‘astonishing hypocrisy’. ‘We show no regard for preventing harm to humans or the environment elsewhere in the world, exporting chemicals deemed too dangerous to use ourselves,’ added Dave Goulson from the University of Sussex.

No comments yet