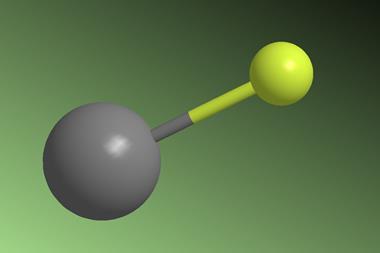

Two chemists are warning that using generative artificial intelligence (GAI) to produce chemistry-related images, such as molecular structures, is leading to serious errors and could end up damaging the education of the next generation of scientists.

Audrey Moores, a chemist specialising in nanoparticles, catalysis and green chemistry at McGill University, Canada, and Vânia Zuin Zeidler, a sustainability chemist at Leuphana University, Germany, joined forces to write a comment piece in Nature Reviews Chemistry in which they called on the chemistry community to ‘ban the use of GAI for any molecule or element representations’ after seeing numerous incorrect structures appearing in presentations and conference materials.

Moores says that what ultimately triggered her to write the opinion piece was a cover in a green chemistry journal where AI had been used to generate chemical structures that, she says, were clearly wrong. ‘It was on LinkedIn, it was really sleek, it was very nice. And [then] you [really] looked at it and the chemical structures were wrong.’

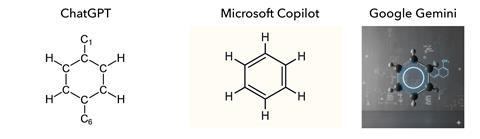

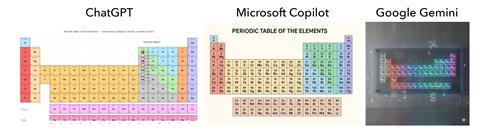

Moores says that she has played with the likes of ChatGPT and Copilot and asked both to produce different visuals for an inorganic chemistry course she teaches. ‘I wanted to make different illustrations for my course, and it was a disaster … specifically I asked Copilot to represent inorganic chemistry and I asked for the periodic table, and it was not at all the periodic table. I did a lot of prompt engineering to try to make it better, and it was clearly not able to handle that.’

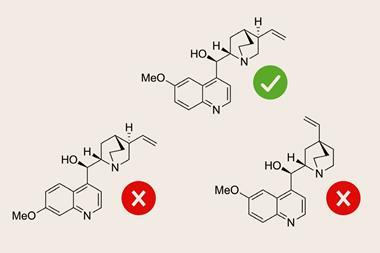

However, she stresses that the problem is not AI itself and that GAI has many useful applications for chemists. The issue, she says, is specifically related to chemical structures and the fact that, in a lot of cases, due diligence is not being applied when using AI for this purpose.

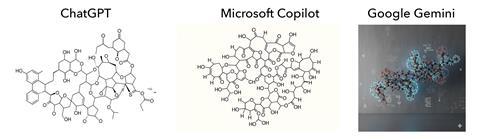

‘I don’t think we’re paying enough attention to this,’ says Moores. She says that when you first look at a generative AI picture, it’s superficially correct and your response is ‘Oh, it looks really sleek. It’s beautiful’. But she adds that ‘it takes a few more minutes of observing to get to, “oh my god, this is wrong”.’

‘The problem is that we tend to sometimes live in a world in which the second step is just never taking place, and so I think it’s easy to fool people. We need to be careful and we need to spend this extra time to look at things so that we can really see beyond the façade,’ she adds. ‘There’s a lot to learn from that perspective when we teach chemistry to really teach students to have this layered approach when they’re observing.’

In their article Moores and Zuin Zeidler warn that the inability of current GAI to generate representations of chemistry that are accurate and useful will not only have important consequences for the ability of the next generation to learn about chemistry but also change the way the chemistry community thinks and looks at itself. ‘The problem I see with generative AI is that for the first time, it’s started to create representation of chemistry that have not come from a thoughtful and [considered] decision from chemists of “let’s represent it this way because…”. Now we have an entity somewhere that decides “I’m going to make a benzene ring that is not even closing”,’ says Moores.

Publishing guidelines

Nature has decided that, for the foreseeable future and excepting articles that are specifically about AI, they will ‘not be publishing any content in which photography, videos or illustrations have been created wholly or partly using generative AI’.

Other publishers have issued their own guidance on the use of GAI for visual content.

The Royal Society of Chemistry’s guidance on visual content for individual journals states: ‘If using AI tools to help create the [graphic/cover artwork], authors must confirm that the AI tool has been trained using fully licensed datasets and the terms of the licence to use the AI output allow commercial reuse.’

Elsevier does not permit the use of GAI or AI-assisted tools to create or alter images in submitted manuscripts. This includes enhancing, obscuring, moving or removing, or introducing a specific feature within an image or figure. It says the only exception is if the use of AI or AI-assisted tools is part of the research design or research methods. However, it says this must be done in a ‘reproducible manner’ and include an explanation of how the tools were used.

Elsevier states that in some cases GAI can be used to produce cover art, if the author obtains prior permission from the journal editor and publisher, can demonstrate that all necessary rights have been cleared for the use of the relevant material and ensures that there is correct content attribution.

A spokesperson for Wiley told Chemistry World that it does not permit the use of AI to generate or modify images that support scientific, clinical or technical claims. ‘In cases where AI use is permissible, for instance by visualising a researcher’s data, we require disclosure of the use,’ they add.

However, Moores and Zuin Zeidler believe a stronger stance than that of Nature is needed, and that the chemistry community should ban the use of GAI ‘for any molecule or element representations in their visual content for as long as they create the major errors discussed herein’.

‘With the current state of AI, we should not let AI generate molecules,’ says Moores. ‘If you need to use AI for creative content, go ahead, but then paste your molecules yourself. We think that, for now, we should not let AI draw chemistry until it’s better at it,’ she notes. ‘We have a responsibility as scientists when we represent the world, to be attentive to how we do it, because it has consequences on how we see the world.’

References

A Moores and V Zuin Zeidler, Nat. Rev. Chem., 2025, DOI: 10.1038/s41570-025-00757-9

1 Reader's comment