A team at Wageningen University and TNO in the Netherlands has designed a device the enables reliable point-of-care tests for Covid-19 but is also cheap and easy to make. They are freely sharing the instructions to make the test to maximise its impact and accelerate uptake in remote and low-income regions.

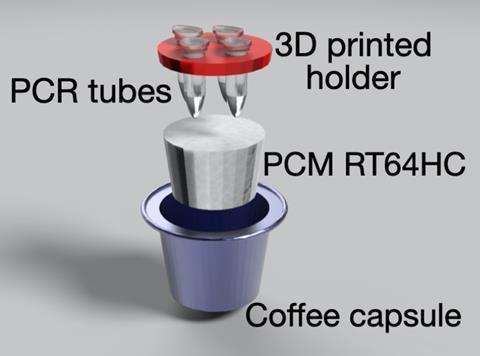

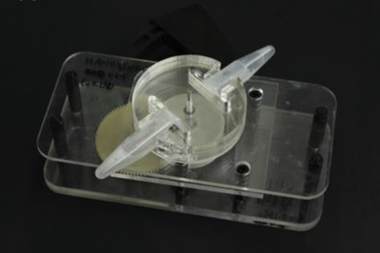

The team created their test by recycling empty aluminium coffee capsules into miniature chemical reactors. ‘We designed a 3D-printed plastic holder that fits four Eppendorf vials to perform the tests,’ explains Vittorio Saggiomo, who led the study. ‘We get the results in just 30 minutes.’

This new device uses loop-mediated isothermal amplification (Lamp), a reaction that heats different primers and enzymes to make several copies of the virus’ genetic material. If Sars-CoV-2 is present in the saliva sample, the Lamp reaction acidifies the solution, which is easily detected using a pH indicator such as phenol red. ‘It’s a very striking colour change – negatives are pink, and positives are yellow,’ says Saggiomo.

To make the test even more accessible, researchers discovered a way to heat samples without the need for electricity. ‘We filled the capsules with a phase-changing material, a wax that melts at 64°C,’ Saggiomo says. As temperature remains constant during phase changes, users just need to place the capsules in a pot with boiling water. ‘This wax is like paraffin, it is really cheap, the whole device costs under 20p,’ he adds. Moreover, the same capsule can be used many times, without generating any unwanted waste. ‘At the end of its life cycle, the aluminium can be recycled, the paraffin burned and the 3D-printed plastic biodegraded,’ says Saggiomo.

Simon Lewis, an analytical chemist who has developed frugal forensic tests at Curtin University, Australia, says creating point-of-care solutions for developing countries and remote areas is ‘a remarkable challenge’. ‘Often advanced analytical techniques are only optimised for lavishly equipped laboratories,’ he adds. For Covid-19, he says that we need tests that are safe, cheap and reliable even in remote locations. ‘However, we still need to validate the technology to assess if it’s fit for purpose,’ he adds.

‘This approach demonstrates the versatility of 3D-printing,’ says Henry Powell-Davies, a doctoral student at the University of Glasgow, UK, who develops 3D-printed labware. ‘These innovations will make Covid testing more efficient and democratic, streamlining an otherwise very invasive procedure.’

Saggiomo still wants to improve the tests further. Currently, the procedure requires an RNA extraction step before the test, which adds a layer of complexity. ‘Ideally, we would love to test saliva directly,’ he explains. Besides, researchers are confident they could adapt this methodology for other infectious diseases. ‘As long as we change the Lamp primers and enzymes, this would provide a very adaptable testing solution for many different purposes, from disease screenings in low-income settings to citizen science,’ he says.

References

A Velders et al, ChemRxiv, 2021, DOI: 10.26434/chemrxiv.14224481.v1

No comments yet