When it was announced in 2023 that the world’s first Crispr-based gene-editing therapy had been approved in the UK there was much excitement. After all, it was a mere three years since the development of this gene-editing tool was recognised with the Nobel prize in chemistry. It went from lab tool to the clinic to market in record time.

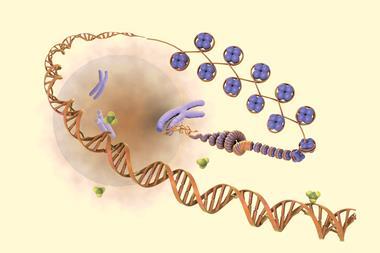

The creation of Casgevy (exagamglogene autotemcel) was a scientific masterclass. The treatment was developed to help those with sickle cell disease and β-thalassaemia – crippling genetic disorders that warp red blood cells and can leave sufferers in great pain, struggling to lead normal lives. Its approach was innovative. Casgevy wasn’t designed to tackle the faulty genes associated with misshapen haemoglobin in these diseases – a tricky prospect – instead it snipped and disrupted a single gene that stops us from making foetal haemoglobin. When we were in the womb we all made foetal haemoglobin. This kind of haemoglobin is very similar to adult haemoglobin and can function perfectly well in an adult – the only difference is foetal haemoglobin has a higher affinity for oxygen, allowing a foetus to strip oxygen from its mother’s blood as it flows through the umbilical cord. Guide RNAs lead the Cas9 enzyme – the ‘scissors’ of the gene editor – to a site where they can cut the targeted gene. In theory, once patients start making foetal haemoglobin again, it can take over oxygen transport from the misshapen red blood cells and relieve their symptoms. Brilliant science, I hope we can all agree.

However, despite positive results in clinical trials, early indications from clinicians are that treatment with Casgevy is not quite the cure patients had hoped for. On top of this, the treatment regime is gruelling, with patients’ immune systems needing to be wiped out and the edited stem cells then reintroduced. One clinician we spoke to said that preparing a patient for this kind of stem cell transplant can even lead to deaths as it put such stress on the body and leaves them open to infections following the erasure of their immune system.

In time we’ll get a better understanding of how Casgevy is performing, but as a first-in-class drug with a novel mode of action it was always possible it wouldn’t be plain sailing. However, this is no reason to throw the baby out with the bathwater. Crispr therapies still hold so much promise with trials in the pipeline to treat everything from cancer and HIV to rare genetic conditions. As the technology matures we can expect to see improved treatments for a wide range of diseases, with gene editing potentially taking place in the body, sparing patients from more invasive procedures. There’s still a long road ahead for this technology but these are exciting times for medicine. Let’s see where it takes us.

No comments yet