The UK’s drug agency has become the first to authorise a Crispr gene-editing therapy. The new treatment has been approved for sickle-cell disease and transfusion-dependent β-thalassaemia and has the potential to cure patients with these conditions.

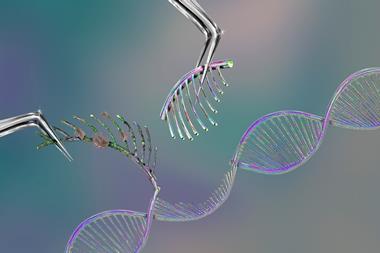

Both genetic conditions are caused by errors in the genes for haemoglobin, a protein found in red blood cells which carries oxygen around the body. Casgevy, manufactured by Vertex Pharmaceuticals and Crispr Therapeutics, uses Crispr to alter a specific gene in a patient’s bone marrow stem cells called BCL11A, to enable the production of a functioning haemoglobin.

To do this, stem cells are taken from the patient’s bone marrow and edited in a laboratory. Patients must then undergo conditioning treatment to prepare the bone marrow before the modified cells are infused back into the patient. The results of the treatment have the potential to be lifelong.

Casgevy has been authorised by the Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA) for patients from 12 years old for whom haematopoietic stem cell transplantation is an appropriate treatment but a suitable donor is not available. Vertex and Crispr Therapeutics estimate that 2000 patients will be eligible for treatment in the UK.

‘Both sickle cell disease and β-thalassaemia are painful, life-long conditions that in some cases can be fatal,’ said Julian Beach, interim executive director of healthcare quality and access at the MHRA. ‘To date, a bone marrow transplant – which must come from a closely matched donor and carries a risk of rejection – has been the only permanent treatment option.’

Fast-tracked treatment

The decision to authorise the Crispr treatment was based on a review of the available evidence including interim outcomes from two ongoing trials. In the sickle cell disease trial, 45 patients have received Casgevy, although only 29 patients have been on the trial long enough to qualify for the primary efficacy interim analysis. Of these patients, 97% were free of painful blood vessel blockages that characterise these diseases for at least 12 months after treatment.

In the transfusion-dependent β-thalassaemia trial, 54 patients received Casgevy, with 42 included in the interim analysis. Of these, 93% did not need a red blood cell transfusion for at least a year after treatment and the remaining three had more than a 70% reduction in the need for transfusions.

Alena Pance, a senior lecturer in genetics at the University of Hertfordshire, said the authorisation was a ‘great step’ to tackle genetic diseases ‘we never thought would be possible to cure’.

‘Modifying the stem cells from the bone marrow of the patient avoids the problems associated with immune compatibility, ie searching for donors that match the patient and following immunosuppression, and constituting a real cure of the disease rather than a treatment,’ she added.

‘The exciting aspect of this is the strategy used for the gene editing because blood diseases can be caused by a number of different mutations that it would be difficult to target individually. This therapy relies on switching off a transcription factor (BCL11A), which is a protein that enables the transition from foetal haemoglobin to adult haemoglobin at birth. This results in the making of foetal haemoglobin that can overcome the defects or absence of the adult beta globin, which makes this approach applicable independently of the specific mutation affecting beta globin present in individual patients.’

Steve Bates, chief executive of the UK Bioindustry Association, said the UK was ‘well set’ to be the first place in the world to license, manufacture and provide access to gene editing treatments via an ‘equitable health system’. ‘Not only do we have today’s world first regulatory approval via the MHRA but we already have in place the NHS innovative medicine fund as an explicit policy route to enable rapid adoption of innovation,’ he added.

In the UK, Casgevy was granted an MHRA ‘innovation passport’ which helps to speed up the approval process with the aim of getting treatments to patients sooner. Vertex said it was already working closely with national health authorities to secure access for eligible patients ‘as quickly as possible’, although it has not yet disclosed the treatment’s price.

No comments yet