A new biocatalytic pathway has been engineered that directly converts aldehydes into amides – essential for many drug molecules. The new approach, which uses oxygen from the air and water as the solvent, was used to redesign the synthetic routes for five drug molecules, demonstrating how it could offer a more sustainable, green and efficient approach for drug synthesis.

Amide bonds are common in drugs because they are chemically stable, form readily and are biocompatible. They also help control properties such as solubility, shape and a molecule’s interactions with proteins in the body. While an amide bond alone doesn’t make something a drug, it is often a crucial structural element that strikes a balance between a molecule’s stability and biological activity.

Usually, amide bonds are made via chemical synthesis by coupling carboxylic acids – which are derived from aldehydes or alcohols – with amines. However, the process requires high-activation-state precursors from acids, protecting group strategies, toxic coupling reagents and transition metal catalysts, as well as large volumes of organic solvents, which generates waste and requires more energy. In recent years, more sustainable, enzymatic routes have been engineered using ATP-dependent ligases; however, these are still dependent on carboxylic acid precursors.

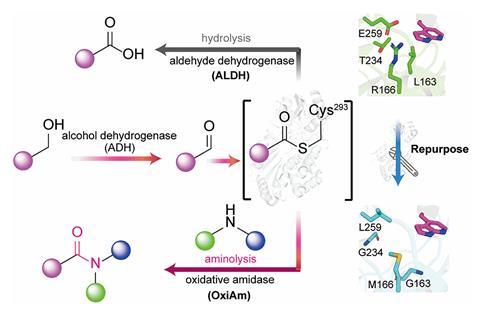

Now, Xiaoguang Lei and colleagues at Peking University, China, have engineered a new biocatalytic and ‘low activation’ pathway that bypasses carboxylic acids altogether, instead synthesising amide bonds directly from aldehydes or, in two-steps, from alcohols.

‘We started by asking whether an enzyme that normally turns aldehydes into carboxylic acids could be persuaded to do something different,’ explains Lei. ‘During its normal reaction, this enzyme, aldehyde dehydrogenase, briefly forms a highly reactive intermediate. We wanted to know if we could redesign the enzyme so that, instead of reacting with water to make an acid, the intermediate would react with an amine to form an amide.’

To do this, the team used protein engineering techniques to reshape the active site of aldehyde dehydrogenase, producing enzymes they dubbed oxidative amidases. When reacting with an aldehyde, the active site allowed an amine to enter and react with the intermediate instead of water, to produce amides directly. When starting from alcohols, a second enzyme was first employed to convert the alcohol to an aldehyde before following the same pathway.

Lei explains that the biggest challenge was stopping water from reacting with the intermediate inside the enzyme while encouraging an amine to outcompete water to be able to ‘hijack’ the intermediate. To do this, the team altered the pH to around 10, which ensured the amine was nucleophilic enough. Meanwhile, hydrophilic residues in the natural enzyme were swapped out with water-repelling ones.

‘Achieving this required careful structural analysis and precise redesign of the enzyme’s active site to control both space and chemical environment,’ says Lei. ‘One surprising result was how few changes to the enzyme were needed to redirect its chemistry completely. Just four targeted mutations were enough to switch the main product from an acid to an amide.’

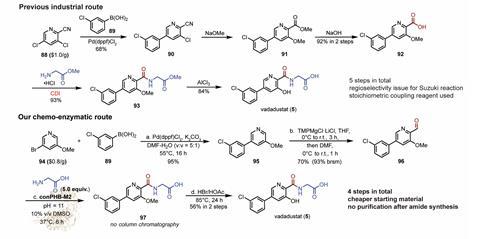

Results revealed that the system worked across many different aldehydes and amines, including substrates relevant to drugs. As proof-of-concept, the researchers demonstrated that the oxidative amidases could streamline the production of five major pharmaceuticals, including drugs used for treating anaemia and leukaemia.

‘The impressive enzyme engineering work by Lei and co-workers provides a new biocatalytic disconnection to amides, starting from amine and aldehyde precursors,’ comments Jason Mickelfield who investigates biocatalysis at Imperial College, London. ‘Any new biocatalytic alternative is valuable, and I am keen to see whether the method proves as versatile as the earlier ATP-dependent ligase approach.’

‘Our long-term hope is that this chemistry will allow chemists to design drug synthesis routes in entirely new ways, starting from simpler and more readily available building blocks such as alcohols,’ says Lei. ‘We are now working on expanding the range of enzymes and substrates, improving efficiency and exploring how this strategy can be applied to industrially relevant pharmaceutical manufacturing.’

References

L Gao et al, Science, 2026, DOI: 10.1126/science.adw3365

No comments yet