Moisturisers, shaving foam and foundation investigated as sources of per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances

Swedish scientists have investigated the levels of a group of notorious fluorinated compounds in cosmetic products. Their findings indicate the presence of fluorinated substances unaccounted for by the listed ingredients, along with high concentrations of substances of concern.

PFASs, or per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances, are linked to adverse health effects and environmental concerns. The chemicals are still produced internationally and are ubiquitous in both commercial products and industrial processes, for applications from textiles to fire-fighting foams. ‘There’s significant contamination in drinking water supplies across the US and really every industrialised country that uses these so they’ve had a lot of attention lately,’ notes Scott Masten, who manages substance selection for the US National Toxicology Program and was not involved in the study. ‘There are so many of them and there’s very little known about which compounds are in cosmetics.’

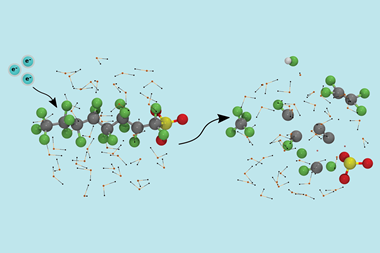

‘A big challenge in this work was to analyse both the listed and unlisted PFAS ingredients, since the concentrations varied so much,’ explains lead scientist Lara Schultes, of Stockholm University. Schultes and her colleagues studied 31 products including moisturising creams, foundations, pencils, powders and shaving foams from brands such as L’Oreal, The Body Shop and Gillette. By testing the products for 39 known PFASs using liquid chromatography with tandem mass spectrometry and comparing these results to their extractable organic fluorine and total fluorine data, the scientists were able to calculate the fluorine mass balance. This is a measure of the fraction of fluorine accounted for by known PFASs and has not been determined in cosmetic products before.

Around half of the samples contained measureable amounts of at least one PFAS. In foundations and powders, the group detected up to 25 PFASs. Some products contained high concentrations of perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA), a suspected carcinogen.

The study highlighted a significant difference between the detected levels of known PFASs and the total fluorine content for all samples, indicating that unknown fluorinated substances are present in these cosmetics. These compounds could result from active ingredients degrading or just be impurities.

Scientists have previously assumed that exposure to PFASs through the skin is negligible compared to routes like dietary intake. However, the group used their data to estimate exposure to PFOA from daily application of foundation and the upper end of their calculated range far exceeds estimates of Swedish daily intake through diet.

PFASs currently serve as emulsifiers and viscosity regulators in cosmetics. However, responding to initial data from this research, several companies have pledged to phase out certain PFASs from their cosmetics. ‘I think we need to ask ourselves whether these chemicals are really needed in certain consumer products,’ says Schultes.

Future work will be to study the dermal absorption of these chemicals in more detail to determine how significant cosmetics are among sources of PFAS exposure.

Correction: This article was updated on 7 December to correct Scott Masten’s job title

References

This article is open access

L Schultes et al, Environ. Sci.: Processes Impacts, 2018, DOI: 10.1039/c8em00368h

No comments yet