Fuel production slowdown will favour more flexible refiners as demand for petrochemicals is stable or increasing

The oil price crash under the weight of the Covid-19 pandemic has brought mixed fortunes for the petrochemical industry. In 2019, the Brent crude benchmark hovered around $60 a barrel, but in April 2020 it crashed below $20/barrel as demand – particularly for fuel – collapsed with society lockdowns. Gradual easing of restrictions has seen prices recover to over $30/barrel.

Typically, global daily consumption is 100 million barrels, but demand was down by 15–20 million barrels/day in April. The demand slump led to brim full inventories especially of gasoline and jet fuel. Complicating matters, while demand for some chemicals has fallen with the shrinking world economic output, demand for others is surging. Refineries are having to adapt, if they can, and some are more flexible than others.

Many crude oil producers lose money once oil prices dip below $50/barrel. ‘As much as 25 million barrels a day of crude is actually losing money,’ says Alan Gelder, refining and chemicals analyst at consultancy Wood Mackenzie.

Shale worries

Much US shale oil production becomes uneconomic when oil dips below $40/barrel. ‘Shale wells in progress are being stopped or suspended, and there are not going to be new wells drilled, for a while’ says James Ray, plastics consultant at ICIS. Some US shale basins produce more gas than oil, however. ‘Marcellus basic accounts for around 35% of all shale gas in the US, and that is all they do,’ explains Hassan Ahmed, an investment analyst at Alembic Global Advisors. ‘Production there continues.’

There is strong incentive. Natural gas prices have ticked upwards, with concerns over reductions in gas produced as a by-product of shale oil operations. This has upended cost disparities in producing ethylene. ‘There are roughly 700,000 different commercially available chemicals,’ says Ahmed, ‘but in terms of volume, 40% of the business of chemistry is done with this one molecule.’

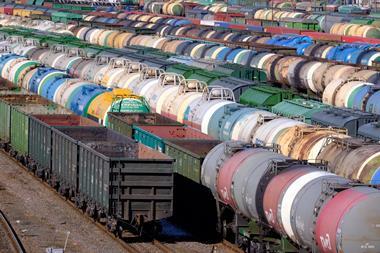

Refiners have invested in increasing the flexibility of their refineries in producing other products, particularly petrochemicals

Ethylene is produced either using naphtha from oil or ethane from natural gas. Facilities in Asia and Europe consumed pricier naphtha, while US producers had access to copious cheap ethane. ‘It looked very attractive to invest in the US Gulf Coast to use ethane to make polyethylene and other ethylene derivatives,’ says Gelder. ‘The oil price collapse has destroyed that competitive advantage.’

Refinery flex

On the face of it, lower oil prices cut input costs for chemical companies and boost their margins. But with consumption of some transport fuels in freefall, refineries do not need to be run as hard, and may cut production even further. ‘Refineries won’t be producing quite as much diesel or gasoline, says Mark Porter, global head of the chemicals at consultancy Bain & Company. As refiners slow down, the supply of some chemical feedstocks is squeezed and prices are rising – particularly with increasing demand for plastic packaging and personal protective equipment (PPE). The misalignment in supply versus demand balances has yet to hit much of the chemical chain.

In low oil scenarios, recycling operations struggle to be competitive, because most of their costs don’t go down with oil prices

Porter says one factor keeping supplies of chemicals on track has been the expansion of Chinese refining capacity, which generates naphtha. Second, lots of oil companies, in planning for reduced fuel demand as transport is electrified, have ‘invested in increasing the flexibility of their refineries in producing other products, particularly petrochemicals,’ says Porter. As a result, at the moment, there is no shortage of petrochemicals.

The pure ethane-based crackers built in the US may turn out to be misjudged investments, says Ahmed. ‘The winner is someone who can quickly change their feedstock between all available options,’ he adds. More adaptable refineries can also vary their product output, Porter explains, ‘So less jet fuel, more naphtha say.’ Even so, no refiner can make excess jet fuel disappear.

The effects on two different solvents used in hand sanitisers exemplify the complicated picture of demand and supply. Ethanol has a huge global market, primarily as a fuel. Prices have dropped about 40%. On the other hand, prices for isopropyl alcohol (IPA), which is made in far smaller quantities and a significant portion goes to hand sanitisers have spiked 170% over the same time period, notes Porter. Some companies reformulated products to use ethanol, while others built new factories to make more IPA products. ‘That is just one example,’ says Porter, ‘but we see that dynamic playing out over and over across the chemicals world.’ At a more granular level it is a mixed bag. Personal care and cleaning products will be in demand, and may well be reformulated to include more antimicrobial ingredients, for example. ‘Electronics, automotive and construction are all likely to head into a downward trend which will overshadow this near term boost, particularly as the market moves into recession and activity declines,’ says Patrick Kirby, petrochemical analyst at Wood Mackenzie.

Reversing circles

Before the pandemic, industry was moving away from single-use plastics and towards greater recycling of plastics. The collapse in oil price will impact the economics of recycling, as virgin plastic costs are nose diving, while recycling processes remain steady or may even go up. ‘Recycling uses labour-intensive supply chains to collect and sort recycled material to bring to processing facilities,’ notes Kirby, and Covid-19 and social distancing rules are likely to disrupt recycling operations. ‘In low oil scenarios, recycling operations struggle to be competitive, because most of their costs don’t go down with oil prices,’ says Ray.

The winner is someone who can quickly change their feedstock between all available options

Also, with an emphasis on hygiene, single use plastics are back in demand, with disposal now seen as preferable to reuse in some items. ‘The fundamentals of the trends are still in place [for more sustainable plastic use],’ says Kilby, but it is likely to be seen as less of a priority.

In terms of transport fuels, a huge boost in demand for oil and gas can be expected once populations return to work. That said, if some trends remain, such as more home-working and less business travel, oil demand would stay lower than pre-pandemic. In the longer term, ‘the fundamentals [of the petrochemicals] industry are still very good,’ Kirby believes. ‘The big driver is the emerging middle classes in Asia Pacific, which consume probably one-tenth of the plastics as in the Western world.’

In the short- to medium-term, capital investment is expected to slide, if not crash. Ahmed says that publicly traded energy and chemical companies will be wary of spending, even after the situation normalises. ‘When times are good, the industry goes and spends like a drunken sailor. When times are bad, the industry curtails production as if the bad times will last forever,’ he says. Gelder agrees that uncertainty will likely mean less capacity will be added than might have been seen otherwise. ‘In the second half of this decade, you could see a cyclical upturn in the industry, as demand solidifies and capacity hasn’t been developed to meet that future demand.’

No comments yet