The UK is on the brink of being frozen out of Europe’s largest research funding programme as a result of political disputes between the British government and the EU.

The deadlock over the UK’s involvement in Horizon Europe is a serious concern for the country’s research community, with university leaders warning that the ‘window for association is closing’. Meanwhile, many UK-based researchers have already lost out on grants and leadership roles on major international projects due to the uncertainty.

The UK’s continued participation in EU research programmes was negotiated as part of the UK–EU Trade and Cooperation Agreement signed on the eve of Brexit in December 2020. But the UK’s status as an associated member of Horizon Europe has never been fully ratified, and has since become a political bargaining chip in the on-going dispute over UK threats to override the Northern Ireland protocol – the customs and immigration deal struck to avoid the need for a hard border on the isle of Ireland.

While the UK government claims that it remains committed to achieving association to programmes like Horizon Europe, Copernicus and organisations like Euratom, science minister George Freeman stated last week that ‘time is running out’ and that the UK is ‘ready to launch’ its own alternative £15 billion research programme if an agreement cannot be reached in a ‘last round’ of talks.

In recent weeks, many organisations representing researchers and institutions have expressed deep concerns about the situation. In a policy briefing document on Horizon Europe, the Russell Group – a body representing 24 of the UK’s top research universities – notes that: ‘The scale, ambition and associated financial risk assumed by the EU programmes, far exceeds anything that could be achieved on a bilateral basis.’ It also highlights the benefits that come with Horizon Europe’s existing funding streams, processes and networks that ‘can be tapped into as soon as association is secured’.

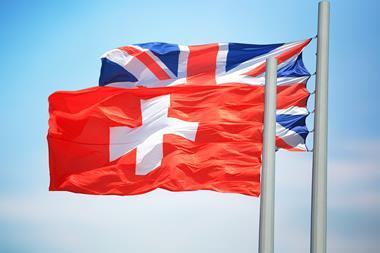

Switzerland finds itself in a similar situation to the UK with political disputes leading to its ejection from Horizon Europe. As a consequence, the UK and Switzerland are now exploring efforts to deepen research ties between the two countries.

Plan B being drawn up

At a recent conference, Tim Bradshaw, the Russell Group’s chief executive, said that the government was right to consider ‘Plan B’ options, but that ‘failure to move forward with UK association would be bad news for research and a second-best outcome for both the UK and the EU’.

‘I can tell you today that the window for association is closing, and closing fast,’ he added. ‘Indeed, it increasingly feels as if we are right on the brink, with association to be snatched away before the summer.’

While UK-based researchers can still be part of Horizon Europe, they cannot sign grant agreements to receive funding from the European commission. The UK government has committed to underwrite the funding for researchers who lose out on grants because of the situation, but it cannot replace the opportunities to lead on international collaborations that are currently unavailable to the country’s researchers. Science Business reports that at least half a dozen UK researchers have lost coordination roles on Horizon Europe consortia, with the true tally ‘likely much higher’.

In a recent letter to commission vice president Maroš Šefčovič, Paul Boyle, who leads on research policy for Universities UK, called for an ‘urgent resolution’ to the situation. ‘Many of our members have reported that their researchers have been forced to leave research consortia that are working on projects that would have a tangible positive impact on European and global prosperity, like improving climate data and addressing food security in sub-Saharan Africa,’ said Boyle. ‘The situation is deteriorating every day that the uncertainty drags on.’

On 8 June more than 140 UK-based researchers who had won European Research Council (ERC) grants were informed that their grants would be terminated. This followed a warning from the ERC in April that unless the grant winners moved to an institution in a participating country, they would be ineligible for funding.

‘The situation is deeply depressing, because continued lack of association is harmful to UK research,’ says Teresa Thurston, a cellular microbiologist based at Imperial College London who was one of the researchers informed that they would lose their ERC grant. ‘There have been great scientists leaving the UK because of this and the longer it continues the worse it will become.’

While the UK funding body UK Research and Innovation should cover the funds for researchers who have missed out on ERC support, Thurston points out that association to Horizon Europe brings more than just financial benefits. ‘I think three things come to mind,’ she tells Chemistry World. ‘The first is alternative UK-based funds that try and replace ERC funding will not carry the prestige, second, they will lack the breadth of network to [help researchers] progress their career, and third, the collaborative opportunities for research across Europe will be significantly harder without association.’

No comments yet