Fernando Gomollón-Bel uncovers a link between his hometown and the 2025 Nobel prize in chemistry

The discovery of metal-organic frameworks has been recognised with the 2025 Nobel prize in chemistry. I was delighted when the decision was announced, and immediately started texting tons of friends in the field. I never worked with MOFs in the lab, however I feel strangely connected to the famous family of porous materials – maybe because of a little-known reference in the literature, dating back to 1973.

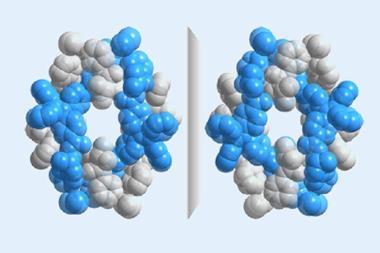

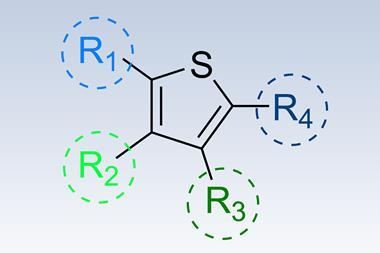

I first encountered MOFs in the process of preparing the first article around Iupac’s Top Ten Emerging Technologies in Chemistry in 2019. I interviewed the now Nobel laureate Omar Yaghi, who already predicted a great number of opportunities. ‘The flexibility of the MOF backbone [leads] to tens of thousands of structures,’ he said, which in turn creates countless applications, including carbon capture, water harvesting, gas storage solutions, and even hinted at biomedical solutions, such as imaging and drug delivery. And, despite the difficulties of divination, Yaghi was right.

My fascination with MOFs continued to the point of pitching papers to Chemistry World almost monthly. Some uncovered unexpected uses of metal-organic frameworks, including a ‘breathing MOF’ that inhales and exhales carbon dioxide, creating a cooling effect that could lead to greener alternatives for refrigeration, and the most mesmerising meltable MOFs, which could constitute stronger screens for smartphones. More recently, industrial applications of MOFs have started to surface. In Spain, the Familia Torres winery piloted applying pellets of metal-organic frameworks for capturing the carbon emissions of fermentation, which could cut down the climate impact of production as well as the costs of securing carbon dioxide for wine preservation.

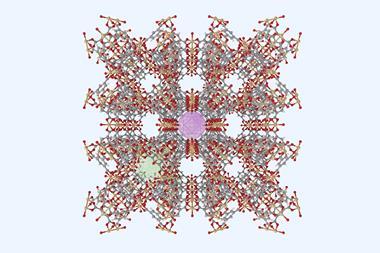

And speaking of Spain – it turns out my own hometown, Zaragoza, could be closely connected to the origins of MOFs. David Fairén-Jiménez, who studies monolithic metal-organic frameworks at the University of Cambridge, UK, pointed me to an arcane article from 1973 in the Journal of the Academy of Exact, Physicochemical and Natural Sciences of Zaragoza that looks into ‘the crystalline structure of iron and cobalt acetates.’ According to Fairén-Jiménez, this is ‘the first ever example of a structure resembling the primordial MOF,’ although at the time, the team didn’t study the compound’s porosity.

Fairén-Jiménez’s team selected the structures of symmetrical square tiles to illustrate one of their papers, which remind me of the Mudéjar architecture in Zaragoza, characteristic in constructions like our cathedral of ‘La Seo’ and St Paul’s church, both recognised as Unesco World Heritage Sites.

Maybe this mysterious manuscript explains my MOF mania. I could delve deeper, assuredly after addressing my addiction to alliterations.

No comments yet