Ben Valsler

Many people live out much of their lives completely unaware that there could be any downside to eating asparagus – it’s delicious and healthy, after all – but those who experience its noxious effects know it all too well. Here’s Helen Arney…

Helen Arney

This episode’s compound might send you round the bend, or at least round the U-bend. It’s responsible for something known in our house as ‘asparagus wee’

We all know it. It’s the pungent, sulfurous aroma that taints your toilet bowl after eating fresh asparagus.

Benjamin Franklin knew it too, as far back as 1781, describing it as a ‘disagreeable odour’ in his essay on flatulence, Fart Proudly.

Even Marcel Proust knew it, although he described it as filling his chamber pot with ‘aromatic perfume’ which makes me wonder what his famous memory of tea-soaked madeleines really smelt like.

I say ‘we all know it’ but actually, my husband doesn’t. Which makes him a very lucky man. Not just to be married to me, but also to have never experienced the repellant scent of asparagus wee.

So what’s going on here?

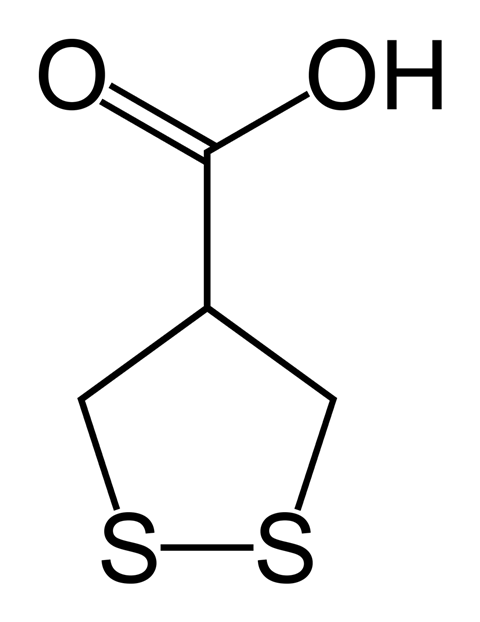

There’s nothing in fresh asparagus itself that smells rancid. But it does contain a unique compound that can’t be found in any other plant: Asparagusic acid. It’s an organosulfur compound, structured from carbon, hydrogen, oxygen and – you’ve guessed it – sulfur.

That’s the element that comes to the fore when asparagusic acid is digested. Yes, it’s your own digestive process that takes asparagusic acid and transforms it into a collection of sulfur-containing compounds including dimethyl sulfide, which smells a lot like boiled cabbage, and methanethiol, another distinctive scent you might recognise from farts and halitosis. Only other people’s, of course. Not yours.

This cocktail of sulfurous metabolites emerges in your urine as volatile organic compounds – that’s both a description of their physics, and of their effect on your nose. Volatile compounds easily evaporate from warm liquid as it exits your body, skittering through the air and into your nose where the scent triggers off a reaction that can also be described as volatile - well, for me at least.

But why do I get all the ‘benefits’ of this extraordinary chemical reaction, and my husband does not?

There are two factors at play here: how the smell is produced, and how the smell is… err… smelled.

First, the matter of production. There’s some debate in the research community about whether different people produce different amounts of these sulfuric compounds after eating asparagus. It’s not a totally far-fetched idea. Different people have different genes, which means everyone produces slightly different combinations of the many metabolic enzymes that break down our food. Some might lack the enzyme that breaks down asparagusic acid and so produce less of the stinky chemicals in question, making it much harder to ‘sniff out’ at the other end, so to speak.

I’ve got to say that I’m a little disappointed that the research conducted in this area is slight, and the results inconclusive. It’s almost like medical researchers don’t have something better to do with their time right now.

However, it’s the second part of the journey from asparagus field to olfactory system that I find more interesting: whether some people are simply unable to smell it.

The research seems to indicate that most people produce asparagus wee but, in the lavatorial lottery that is life, only some of us can detect it with our own nose. The rest have the almost magical gift of ‘asparagus anosmia’.

In a 2016 study, the genetic data of nearly 7,000 participants was recorded along with their ability to smell sulfurous compounds after eating asparagus. 58 percent of men and 61.5 percent of women reported that they didn’t detect a sulfurous smell, making asparagus anosmia a lot more common than I expected, and also offering a real chance to establish a genetic link to this weird phenomenon. By analysing the participant’s answers and their DNA, researchers identified three areas of Chromosome One that seemed to be important for smelling this particular aroma.

So nowadays you can find out your chances of being able to detect asparagus wee without going to the trouble of sourcing, eating and excreting any actual asparagus. If you take a genetic home testing kit, their DNA analysis will give you a percentage chance of being ‘likely to smell asparagus wee’ – alongside other similar genetic dispositions such as whether you’re ‘likely to enjoy coffee’ or ‘dislike coriander’.

It’s possible that the genetic factors which affect production and detection of asparagus wee are interlinked, and perhaps these competing theories are not so separate after all. But my husband doesn’t need to take a DNA test to know his genetic make-up differs massively from mine. As he makes himself a cup of tea, and grudgingly pours me a coffee, or as he picks the coriander leaves out of a salad I’ve lovingly prepared for him, I remind him that one of us is a genetic mutant, and I think it’s probably him. But he’s my genetic mutant, and I wouldn’t swap him for all the organosulfates in the world.

Ben Valsler

That was Helen Arney from the Festival of the Spoken Nerd – you can catch the entire first series of their Podcast of Unnecessary Detail now on their website, or through your preferred podcast platform. Next week, Mike Freemantle keeps bacteria at bay…

Mike Freemantle

Every antiseptic has its pros and cons. Chlorhexidine salts have a broad-spectrum of biocidal activity. They are also fast acting, although not as fast as the alcohols ethanol and iso-propanol that are currently employed as antiseptic ingredients in the ubiquitous alcohol-based hand sanitisers.

Ben Valsler

So if you’re looking for an alternative to alcohol to keep your hands hygienic when you’re away from soap and water, join Mike next time to learn more. And until then, please do get in touch if there are any compounds you would like us to cover – email chemistryworld@rsc.org or tweet @chemistryworld. And visit chemistryworld.com/podcasts to find the entire podcast archive. Thank you for joining me, I’m Ben Valsler.

Additional information

Theme: Opifex by Isaac Joel, via Soundstripe

No comments yet